You are browsing the archive for Chronicles of the Cape.

The First Burghers at the Cape

May 28, 2009 The preliminary arrangements for releasing some of the Company’s servants from their engagements and helping them to become farmers were at length completed, and on the 21st of February 1657 ground was allotted to the first burghers in South Africa. Before that date individuals had been permitted to make gardens for their own private benefit, but these persons still remained in the Company’s service. They were mostly petty officers with families, who drew money instead of rations, and who could derive a portion of their food from their gardens, as well as make a trifle occasionally by the sale of vegetables. The free burghers, as they were afterwards termed, formed a very different class, as they were subjects, not servants of the Company. For more than a year the workmen as well as the officers had been meditating upon the project, and revolving in their minds whether they would be better off as free men or as servants. At length nine of them determined to make the trial. They formed themselves into two parties, and after selecting ground for occupation, presented themselves before the Council and concluded the final arrangements. There were present that day at the Council table in the Commander’s hall, Mr Van Riebeek, Sergeant Jan van Harwarden, and the Bookkeeper Roelof de Man. The proceedings were taken down at great length by the Secretary Caspar van Weede.

The preliminary arrangements for releasing some of the Company’s servants from their engagements and helping them to become farmers were at length completed, and on the 21st of February 1657 ground was allotted to the first burghers in South Africa. Before that date individuals had been permitted to make gardens for their own private benefit, but these persons still remained in the Company’s service. They were mostly petty officers with families, who drew money instead of rations, and who could derive a portion of their food from their gardens, as well as make a trifle occasionally by the sale of vegetables. The free burghers, as they were afterwards termed, formed a very different class, as they were subjects, not servants of the Company. For more than a year the workmen as well as the officers had been meditating upon the project, and revolving in their minds whether they would be better off as free men or as servants. At length nine of them determined to make the trial. They formed themselves into two parties, and after selecting ground for occupation, presented themselves before the Council and concluded the final arrangements. There were present that day at the Council table in the Commander’s hall, Mr Van Riebeek, Sergeant Jan van Harwarden, and the Bookkeeper Roelof de Man. The proceedings were taken down at great length by the Secretary Caspar van Weede.

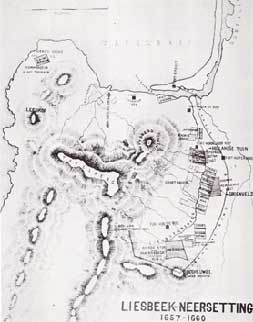

The first party consisted of five men, named Herman Remajenne, Jan de Wacht, Jan van Passel, Warnar Cornelissen, and Roelof Janssen. They had selected a tract of land just beyond Liesbeek, and had given to it the name of Groeneveld, or the Green Country. There they intended to apply themselves chiefly to the cultivation of wheat. And as Remajenne was the principal person among them, they called themselves Herman’s Colony. The second party was composed of four men, named Stephen Botma, Hendrik Elbrechts, Otto Janssen, and Jacob Cornelissen. The ground of their selection was on this side of the Liesbeek, and they had given it the name of Hollandsche Thuin, or the Dutch Garden. They stated that it was their intention to cultivate tobacco as well as grain. Henceforth this party was known as Stephen’s Colony. Both companies were desirous of growing vegetables and of breeding cattle, pigs, and poultry.

The conditions under which these men were released from the Company’s service were as follows :

They were to have in full possession all the ground which they could bring under cultivation within three years, during which time they were to be free of taxes. After the expiration of three years they were to pay a reasonable land tax. They were then to be at liberty to sell, lease, or otherwise alienate their ground, but not without first communicating with the Commander or his representative. Such provisions as they should require out of the magazine were to be supplied to them at the same price as to the Company’s married servants. They were to be at liberty to catch as much fish in the rivers as they should require for their own consumption.

They were to be at liberty to sell freely to the crews of ships any vegetables which the Company might not require for the garrison, but they were not to go on board ships until three days after arrival, and were not to bring any strong drink on shore. Called Stephen Janssen, that is Stephen the son of John, in the records of the time. More than twenty years later he first appears as Stephen Botma. From him sprang the present large South African family of that name.

They were not to keep taps, but were to devote themselves to the cultivation of the ground and the rearing of cattle. They were not to purchase horned cattle, sheep, or anything else from the natives, under penalty of forfeiture of all their possessions.

They were to purchase such cattle as they needed from the Company, at the rate of twenty-five gulden for an ox or cow and three gulden for a sheep.

They were to sell cattle only to the Company, but all they offered were to be taken at the above prices.

They were to pay to the Company for pasturage one tenth of all the cattle reared, but under this clause no pigs or poultry were to be claimed.

The Company was to furnish them upon credit, at cost price in the Fatherland, with all such implements as were necessary to carry on their work, with food, and with guns, powder, and lead for their defence. In payment they were to deliver the produce of their ground, and the Company was to hold a mortgage upon all their possessions.

They were to be subject to such laws as were in force in the Fatherland and in India, and to such as should thereafter be made for the service of the Company and the welfare of the community. These regulations could be altered or amended at will by the Supreme Authorities. The two parties immediately took possession of their ground and commenced to build themselves houses.

They had very little more than two months to spare before the rainy season would set in, but that was sufficient time to run up sod walls and cover them with roofs of thatch. The forests from which timber was obtained were at no great distance; and all the other materials needed were close at hand. And so they were under shelter and ready to turn over the ground when the first rains of the season fell. There was a scarcity of farming implements at first, but that was soon remedied.

On the 17th of March a ship arrived from home, having on board an officer of high rank, named Ryklof van Goens, who was afterwards Governor General of Netherlands India, He had been instructed to rectify anything that he might find amiss here, and he thought the conditions under which the burghers held their ground could be improved. He therefore made several alterations in them, and also inserted some fresh clauses, the most important of which are as follows:

1. The freemen were to have plots of land along the Liesbeek, in size forty roods by two hundred – equal to 133 morgen – free of fixes for twelve years.

2. All farming utensils were to be repaired free of charge for three years. In order to procure a good stock of breeding cattle, the free-men were to be at liberty to purchase from the natives, until further instructions should be received, but they were not to pay more than the Company.

3. The price of horned cattle between the freemen and the Company was reduced from twenty-five to twelve gulden.

The penalty to be paid by a burgher for selling cattle except to the Company was fixed at twenty rix-dollars.

4. That they might direct their attention chiefly to the cultivation of grain, the freemen were not to plant tobacco or even more vegetables than were needed for their own consumption.

5. The burghers were to keep guard by turns in any redoubts which should be built for their protection.

6. They were not to shoot any wild animals except such as were noxious. To promote the destruction of ravenous animals the premiums were increased, viz, for a lion, to twenty-five gulden, for a hyena, to twenty gulden, and for a leopard, to ten gulden.

7. None but married men of good character and of Dutch or German birth were to have ground allotted to them. Upon their request, their wives and children were to be sent to them from Europe. In every case they were to agree to remain twenty years in South Africa.

8. Unmarried men could be released from service to work as mechanics, or if they were specially adapted for any useful employment, or if they would engage themselves for a term of years to the holders of ground.

9. One of the most respectable burghers was to have a seat and a vote in the Council of Justice whenever cases affecting freemen or their interests were being tried. He was to hold the office of Burgher Councillor for a year, when another should be selected and have the honour transferred to him.

To this office Stephen Botma was appointed for the first term. The Commissioner drew up lengthy instructions for the guidance of the Cape government, in which the Commander was directed to encourage and assist the burghers, as they would relieve the Company of the payment of a large amount of wages. There were then exactly one hundred persons in South Africa in receipt of wages, and as soon as the farmers were sufficiently numerous, this number was to be reduced to seventy.

Many of the restrictions under which the Company’s servants became South African burghers were vexatious, and would be deemed intolerable at the present day. But in 1657 men heard very little of individual rights or of unrestricted trade. They were accustomed to the interference of the government in almost every thing, and as to free trade, it was simply impossible. The Netherlands could only carry on commerce with the East by means of a powerful Company, able to conduct expensive wars and maintain great fleets without drawing upon the resources of the State. Individual interests were therefore lost sight of even at home, much more so in such a settlement as that at the Cape, which was called into existence by the Company solely and entirely for its own benefit.

A commencement having been made, there were a good many applications for free papers. Most of those to whom they were granted afterwards re-entered the Company’s service, or went back to the Fatherland. The names of some who remained in South Africa have died out, but others have numerous descendants in this country at the present day. There are even instances in which the same Christian name has been transmitted from father to son in unbroken succession. In addition to those already mentioned, the following individuals received free papers within the next twelvemonth : Wouter Mostert, who was for many years one of the leading men in the settlement. He had been a miller in the Fatherland, and followed the same occupation here after becoming a free burgher. The Company had imported a corn mill to be worked by horses, but after a short time it was decided to make use of the water of the fresh river as a motive power. Mostert contracted to build the new mill, and when it was in working order he took charge of it on. shares of the payments made for grinding. Hendrik Boom, the gardener, whose name has already been frequently mentioned.

Caspar Brinkman, Pieter Visagie, Hans Faesbenger, Jacob Cloete, Jan Reyniers, Jacob Theunissen, Jan Rietvelt, Otto van Vrede, and Simon Janssen, who had land assigned to them as farmers. Herman Ernst, Cornelis Claassen, Thomas Robertson (an Englishman), Isaac Manget, Klaas Frederiksen, Klaas Schriever, and Hendrik Fransen, who took service with farmers.

Christian Janssen and Peter Cornelissen, who received free papers because they had been expert hunters in the Company’s service. It was arranged that they should continue to follow that employment, in which they were granted a monopoly, and prices were fixed at which they were to sell all kinds of game they were also privileged to keep a tap for the sale of strong drink.

Leendert Cornelissen, a ship’s carpenter, who received a grant of a strip of forest at the foot of the mountain. His object was to cut timber for sale, for all kinds of which pries were fixed by the Council.

Elbert Dirksen and Hendrik van Surwerden, who were to get living as tailor.

Jan Vetteman, the surgeon of the fort. He arranged for a monopoly of practice in his profession and for various other privileges.

Roelof Zieuwerts, who was to get his living as a waggon and plough maker, and to whom a small piece of forest was granted.

Martin Vlockaart, Pieter Jacobs, and Jan Adriansen, who were to maintain themselves as fishermen.

Pieter Kley, Dirk Vreem, and Pieter Heynse, who were to saw yellow wood planks for sale, as well as to work at their occupation as carpenters’.

Hendrik Schaik, Willem Petersen, Dirk Rinkes, Michiel van Swel, Dirk Noteboom, Frans Gerritsen, and Jan Zacharias, who are mentioned merely as having become free burghers. Besides the regulations concerning the burghers, the Commissioner Van Goons drew up copious instructions on general subjects for the guidance of the government. He prohibited the ompany’s servants from cultivating larger gardens than required or their own use, but he excepted the Commander, to whom he granted the whole of the ground at Green Point as a private farm. As a rule, the crews of foreign ships were not to be provided with vegetables or meat, but were to be permitted to take in water freely. The Commander was left some discretion in dealing with hem, but the tenor of the instructions was that they were not to be, encouraged to visit Table Bay.

Regarding the natives, they were to be treated kindly, so as to obtain their goodwill. If any of them assaulted or robbed a burgher, those suspected should be seized and placed upon Robben Island until they made known the offenders, when they should be released and the guilty persons be banished to the island for two or three years. If any of them committed murder, the criminal should be put to death, but the Commander should endeavour have the execution performed by the natives themselves. Caution was to be observed that no foreign language should continue to be spoken by any slaves who might hereafter be brought into the country. Equal care was to be taken that no other weights or measures than those in use in the Fatherland should be introduced. The measure of length was laid down as twelve Rhynland inches to the foot, twelve-feet to the rood, and two thousand roods to the mile, so that fifteen miles would be equal to a degree of latitude. In measuring land, six hundred square roods were to make a morgen. The land measure thus introduced is used in the Cape Colony to the present day. In calculating with it, it must be remembered that one thousand Rhynland feet are equal to one thousand and thirty-three British Imperial feet. The office of Secunde, now for a long time vacant, was filled by the promotion of the bookkeeper Roelof de Man. Caspar van Weede was sent to Batavia, and the clerk Abraham Gabbema was appointed Secretary of the Council in his stead. In April 1657, when these instructions were issued, the European population consisted of one hundred and thirty-four individuals, Company’s servants and burghers, men, women, and children all told. There were at the Cape three male and eight female slaves.

Commissioner Van Goens permitted the burghers to purchase cattle from the natives, provided they gave in exchange no more than the Company was offering. A few weeks after he left South Africa, three of the farmers turned this license to account, by equipping themselves and going upon a trading journey inland. Travelling in an easterly direction, they soon reached a district in which five or six hundred Hottentots were found, by whom they were received in a friendly manner. The Europeans could not sleep in the huts on account of vermin and filth, neither could they pass the night without some shelter, as lions and other wild animals were numerous in that part of the country. The Hottentots came to their assistance by collecting a great quantity of thorn bushes, with which they formed a high circular hedge, inside of which the strangers slept in safety. Being already well supplied with copper, the residents were not disposed to part with cattle, and the burghers were obliged to return with only two oxen and three sheep. They understood the natives to say that the district in which they were living was the choicest portion of the whole country, for which reason they gave it the name of Hottentots Holland.

For many months none of the pastoral Hottentots had been at the fort, when one day in July Harry presented himself before the Commander. He had come, he said, to ask where they could let their cattle graze, as they observed that the Europeans were cultivating the ground along the Liesbeek. Mr Van Riebeek replied that they had better remain where they were, which was at distance of eight or ten hours’ journey on foot from the fort. Harry informed him that it was not their custom to remain long in one place, and that if they were deprived of a retreat here they would soon be ruined by their enemies. The Commander then rated that they might come and live behind the mountains, along by Hout Bay, or on the slope of the Lion’s Head, if they would trade with him. But to this Harry would not consent, as he said they lived upon the produce of their cattle. The native difficulty had already become what it has been ever since, the most important question for solution in South Africa. Mr Van Riebeek was continually devising some scheme for its settlement, and a large portion of his dispatches has reference to the subject. At this time his favourite plan was to build a chain of redoubts across the isthmus and to connect them with a wall.

A large party of the Kaapmans was then to be enticed within the line, with their families and cattle, and when once on this side none but men were ever to be allowed to go beyond it again. They were to be compelled to sell their cattle, but were to be provided with goods so that the men could purchase more, and they were to be allowed a fair profit on trading transactions. The women and children were to be kept as guarantees for the return of the men. In this manner, the Commander thought, a good supply of cattle could be secured, and all difficulties with the natives be removed.

During the five years of their residence at the Cape, the Europeans had acquired some knowledge of the condition of the natives. They had ascertained that all the little clans in the neighbourhood, whether Goringhaikonas, Gorachouquas, or Goringhaiquas, were members of one tribe, of which Gogosoa was the principal chief. The clans were often at war, as the Goringhaikonas and the Goringhaiquas in 1652, but they showed a common front against the next tribe or great division of people whose chiefs owned relationship to each other. The wars between the clans usually seemed to be mere forays with a view of getting possession ‘of women and cattle, while between the tribes hostilities were often waged with great bitterness. Of the inland tribes, Mr Van Riebeek knew nothing more than a few names. Clans calling themselves the Chariguriqua, the Cochoqua, and the Chainouqua had been to the fort, and from the last of these one hundred and thirty head of cattle had recently been purchased, but as yet their position with regard to others was not made out. The predatory habits of the Bushmen were well known, as also that they were enemies of every one else, but it was supposed that they were merely another Hottentot clan. Some stories which Eva told greatly interested the Commander.

After the return of the beach rangers to Table Valley, she had gone back to live in Mr Van Riebeek’s house, and was now at the age of fifteen or sixteen years able to speak Dutch fluently.

The ordinary interpreter, Doman with the honest face, was so attached to the Europeans that he had gone to Batavia with Commissioner Van Goens, and Eva was now employed in his stead. She told the Commander that the Namaquas were a people living in the interior, who had white skins and long hair, that they wore clothing and made their black slaves cultivate the ground, and that they built stone houses and had religious services just the same as the Netherlanders. There were others, she said, who had gold and precious stones in abundance, and a Hottentot who brought some cattle for sale corroborated her statement and asserted that he was familiar with everything of the kind that was exhibited to him except a diamond. He stated that one of his wives had been brought up in the house of a great lord named Chobona, and that she was in possession of abundance of gold ornaments and jewels. Mr Van Riebeek invited him pressingly to return at once and bring her to the fort, but he replied that being accustomed to sit at home and be waited upon by numerous servants, she would be unable to travel so far. An offer to send a wagon for her was rejected on the ground that the sight of Europeans would frighten her to death.

All that could be obtained from this ingenious storyteller was a promise to bring his wife to the fort on some future occasion. After this the Commander was more than ever anxious to have the interior of the country explored, to open up a road to the capital city of Monomotapa and the river Spirite Sancto, where gold was certainly to be found, to make the acquaintance of Chobona and the Namaquas, and to induce the people of Benguela to bring the products of their country to the fort Good Hope for sale. The Commissioner Van Goons saw very little difficulty in the way of accomplishing these designs, and instructed Mr Van Riebeek to use all reasonable exertion to carry them out. The immediate object of the next party which left the fort to penetrate the interior was, however, to procure cattle rather than find Ophir or Monomotapa.

A large fleet was expected, and the Commander was anxious to have a good herd of oxen in readiness to refresh the crews. The party, which left on the 19th of October, consisted of seven servants of the Company, eight freemen, and four Hottentots. They took pack oxen to carry provisions and the usual articles of merchandise. Abraham Gabbema, Fiscal and Secretary of the Council, was the leader. They shaped their course at first towards a mountain which was visible from the Cape, and which, on account of its having a buttress surmounted by a dome resembling a flat nightcap such as was then in common use, had already received the name of Klapmuts. Passing round this mountain and over the low watershed beyond, they proceeded onward until they came to a stream running in a northerly direction along the base of a seemingly impassable chain of mountains, for this reason they gave it the name of the Great Berg River. its waters they found barbels, and by some means they managed to catch as many as they needed to refresh themselves. They were now in one of the fairest of all South African To the west lay a long isolated mountain, its face covered with verdure and here and there furrowed by little streamlets which ran down to the river below. Its top was crowned with domes of bare grey granite, and as the rising sun poured a flood of light upon them, they sparkled like gigantic gems, so that the travellers named them the Paarl and the Diamant. In the evening when the valley lay in deepening shadow, the range on the east was lit up with tints more charming than pen or pencil can describe, for nowhere is the glow of light upon rock more varied or more beautiful. Between the mountains the surface of the ground was dotted over with trees,” and in the month of October it was carpetted with grass and flowers.

Wild animals shared with man the possession of this lovely domain. In the river great numbers of hippopotami were seen ; on the mountain sides herds of zebras were browsing ; and trampling down the grass, which in places was so tall that Gabbema described it as fit to make hay of, were many rhinoceroses.

There is great confusion of names in the early records whenever native clans are spoken of. Sometimes it is stated that Gogosoa’s people called themselves the Goringhaiqua or Goriughaina, at other times the same clan is called the Goringhaikona. Harry’s people were sometimes termed the Watermans, sometimes the Strandloopers (beach rangers). The Bushmen were at first called Visman by Mr Van Riebeek, but he soon adopted the word Sonqua, which he spelt in various ways. This is evidently a form of the Hottentot name for these people, as may be seen from the following words, which are used by a Hottentot clan at the present day :-Nominative singular, sap, a bushman; dual, sakara, two bushmen; plural, sakoa, more than two bushmen. Nominative singular, sas, a bushwoman ; dual, sasara, two bushwomen ; plural, sadi, more than two bushwomen. Common plural, sang, bushmen and bushwomen. When the tribes became better known the titles given in the text were used.

There were little kraals of Hottentots all along the Berg River, but the people were not disposed to barter away their cattle. Gabbema and his party moved about among them for more than a week, but only succeeded in obtaining ten oxen and forty-one sheep, with which they returned to the fort. And so, gradually, geographical knowledge was being gained, and Monomotapa and the veritable Ophir where Solomon got his gold were moved further backward on the charts. During the year 1657 several public works of importance were undertaken.

A platform was erected upon the highest point of Robben Island, upon which a fire was kept up at night whenever ships belonging to the Company were seen off the port. At the Company’s farm at Rondebosch the erection of a magazine for grain was commenced, in size one hundred and eight by forty feet. This building, afterwards known as the Groote Schuur, was of very substantial construction. In Table Valley the lower course of the fresh river was altered. In its ancient channel it was apt to damage the gardens in winter by overflowing its banks. A new and broader channel was therefore cut, so that it should enter the sea some distance to the south-east of the fort. The old channel was turned into a canal, and sluices were made in order that the moat might still be filled at pleasure.

In February 1658 it was resolved to send another trading party inland, as the stock of cattle was insufficient to meet the wants of the fleets shortly expected. Of late there had been an unusual demand for meat. The Arnhem, and Slot van Honingen, two large East Indiamen, had put into Table Bay in the utmost distress, and in a short time their crews had consumed forty head of horned cattle and fifty sheep. This expedition was larger and better equipped than any yet seat from the fort Good Hope. The leader was Sergeant Jan van Harwarden, and under him were fifteen Europeans and two Hottentots, with six pack oxen to carry provisions and the usual articles of barter. The Land Surveyor Pieter Potter accompanied party for the purpose of observing the features of the country, so that a correct map could be made.

To him was also entrusted the task of keeping the journal of the expedition. The Sergeant instructed to learn all that he could concerning the tribes, to ascertain if ivory, ostrich feathers, musk, civet, gold, and precious stones, were obtainable, and, if so, to look out for a suitable place the establishment of a trading station. The party passed the Paarl mountain on their right, and crossing the Berg River beyond, proceeded in a northerly direction until they reached the great wall which bounds the coast belt of South Africa. In searching along it for a passage to the interior, they discovered a stream which came foaming down through an enormous cleft in the mountain, but they could not make their way along it, as the sides of the ravine appeared to rise in almost perpendicular precipices. It was the Little Berg River, and through the winding gorge the railway to the interior passes today, but when in 1658 Europeans first looked into its deep recesses it seemed to defy an entrance.

The travellers kept. on their course along the great barrier, but no pathway opened to the regions beyond. Then dysentery attacked some of them, probably brought on by fatigue, and they were compelled to retrace their steps. Near the Little Berg River they halted and formed a temporary camp, while the Surveyor Potter with three Netherlanders and the two Hottentots attempted to cross the range. It may have been at the very spot known a hundred years later as the Roodezand Pass, and at any rate it was not far from it, that Potter and his little band toiled wearily up the heights, and were rewarded by being the first of Christian blood to look down into the secluded dell now called the Tulbagh Basin.

Standing on the summit of the range, their view extended away for an immense distance along the valley of the Breede River, but it was a desolate scene that met their gaze. Under the glowing sun the ground lay bare of verdure, and in all that wide expanse which today is dotted thickly with cornfields and groves and homesteads, there was then no sign of human It was only necessary to run the eye over it to be assured that the expedition was a failure in that direction. And so they returned to their companions and resumed the homeward march.

Source: Chronicles of the Cape Commanders by George McCall Theal – 1882

Recommended Reading Books of the Early Cape

May 28, 2009The quest for information on our ancestors is on going and daunting task especially when you are looking for information that you think is not available or not well documented. Many people would be pleasantly surprised if they new how much research and data there is available for people living at the Cape as early as 1652.

A major source of reference is that of George McCall Theal whose volumes of rich history cover over two centuries of important historical works that are one a of kind.

Theal’s frank and often blunt description of authors work can be found in a number of his “Chronicles of the Cape ” and “History of South Africa”.

Below is a list of primary reading resources for Cape History extracted from Theal’s works. These books can be found in the National Library of South Africa as well as in private collections and University Libraries:

de Barros, Joano: Da Asia. Barros, who lived from 1496 to 1570, held important offices under the Crown of Portugal. From 1522 to 1525 he was Governor of St George del Mina on the West Coast of Africa, after which he became Treasurer of the Indian branch of the Revenue, Councillor, and Historian. The first decade of his work was published at Lisbon in 1552, the second in 1553, the third in 1563, and the fourth not until after its author’s death. In compiling the narratives of the first voyages Barros had the advantage of reference to the journals kept by the officers of the expeditions. The edition of his work in the South African Public Library was published at Lisbon in nine volumes in 1778. There is a Dutch translation of the Voyages of the First Explorers and of the successive Indian Fleets, published at Leiden in 1707.

Osorius, Hieronymus: De Rebus Emmanuelis Regis Lusitanice. Lisbon, 1571. This work has always been regarded as one of great authority. Its author, who was Bishop of Silves, was a man of high education, with a fondness for research and an exceedingly graceful style of writing. He lived from 1506 to 1580. His work covers a period of twenty-six years, the most glorious in the history of Portugal. There is a recent edition in three volumes in the original Latin in the South African Public Library, and I have also a translation in Dutch made by Francois van Hoogstraeten, and published in two volumes at Rotterdam in 1661. This translation is entitled Leven en Deurluchtig Bedrijf van Emanuel den Eersten, Koning van Portugael, behelzende d’ Ontdecking van Oost Indien, en derzwaerts de eerste Tochten der Portugezen, c.

Correa, Gaspar: Lendas da India. This work is well known to English readers from the translation entitled The Three Voyages of Vasco da Gama and his Viceroyalty, published at London for the Hakluyt Society in 1869. About the year 1514 Correa went to India, where, during the following half century, he filled situations which gave him opportunities of becoming well acquainted with what was transpiring. There, towards. the close of his life, he wrote his history, which is an account of the transactions of the Portuguese in the East during a period of fifty-three years. The manuscript was removed to Portugal in 1583, but the work was not published until 1858, when it was printed at Lisbon. The dates given by Correa differ considerably from those of Osorius and Barros. Thus he makes Da Gama sail from Lisbon in March 1497, while both Osorius and Barros state that the expedition left in July of that year. He differs also in many respects from those writers in his account of events.

van Linschoten, Jan Huyghen: various works published in 1595 and 1596. See first chapter. Eerste Schipvaert der Hollanders naer Oost Indien, met vier Schepen onder ‘t beleydt van Cornelis Houtman uyt Texel ghegaen, Anno 1595. Contained in the collection of voyages known as Begin ende Voortgangh van de Vereenighde Nederlantsche Geoctro- yeerde Oost Indische Compagnie, printed in 1646, and also published separately in quarto at Amsterdam in 1648, with numerous subsequent editions. The original journals kept in the different ships of this fleet are still in existence, from which it is seen that the printed work is only a compendium. While at the Hague I made verbatim copies for the Cape Government of those portions of the original manuscripts referring to South Africa, and I found that one or two curious errors had been made by the compiler of the printed journal. As an instance, the midshipman Frank van der Does, in the ship Hollandia, when describing the Hottentots, states, ” Haer haer opt hooft stadt oft affgeschroijt waer vande zonne, ende sien daer wyt eenich gelyck een dieff die door het langhe hanghen verdroocht is .” This is given in the printed journal, ” Het hayr op hare hoofden is als ‘t hayr van een mensche die een tijdt langh ghehanghen heeft ,” an alteration which turns a graphic sentence into nonsense.

Begin ende Voortgangh van de Vereenighde Nederlantsche Geoctroyeerde Oost Indische Compagnie, vervatende de voornaemste Reysen by de Inwoonderen derselver Provincien derwaerts gedaen. In two thick volumes. Printed in 1646. This work contains the journals in a condensed form of the fleets under Cornelis Houtman, Pieter Both, Joris van Spilbergen, and others, as also the first charter of the East India Company.

Journael van de Voyagie gedaen met drie Schepen, genaemt den Ram, Schaep, ende het Lam, gevaren uyt Zeelandt, van der Stadt Camp-Vere, naer d’ Oost Indien, onder ‘t beleyt van den Heer Admirael Joris van Spilbergen, gedaen in de jaren 1601, 1602, 1603, en 1604. Contained in the collection of voyages known as Begin ende Voortgangh van de Vereenighde Nederlantsche Geoctroyeerde Oost Indische Compagnie, printed in 1646, and also published separately in quarto at Amsterdam in 1648, with numerous editions thereafter. An account of the naming of Table Bay is to be found in this work.

Shillinge, Andrew: An account of a voyage to Surat in the years 1620-1622. I have been unable as yet to obtain a copy of this pamphlet in the original English. A Dutch translation, entitled Kort Dagverhaal van de Zee-Togt na Suratte en Jasques in de Golf van Persien, gedaan in het jaar 1620, en vervolgens, was published at Leiden in 1707. It is only twelve pages in length, but in it is recorded the declaration of English sovereignty over Table Bay and the surrounding country. A copy of the declaration is to be found in the first volume of the first edition of Barrow’s Account of Travels into the Interior of Southern Africa, published at London in 1801.

Herbert, Sir Thomas: Some Years Travels into Divers Parts of Africa and Asia the Great. The second edition was published at London in 1638, the fourth in 1677. The author when on his way eastward called at Table Bay in July 1626, and remained here nineteen days. Seven pages of a moderately sized volume are devoted to an account of this visit. He states that at Agulhas there was little or no variation of the compass, while in Table Valley he found the westerly variation one degree and forty minutes. Herbert’s description of the people, whom he called Hattentotes (sic), is in some respects hardly more correct than his estimate of the height of Table Mountain, which he sets down as eleven thousand eight hundred and sixty feet. The work is interesting rather as a curiosity than on account of any information to be obtained from it.

Hondius, Jodocus (publisher,-author’s name not given): Klare ende Korte Besgryvinge van het Land aan Cabo de Bona Esperance. A little work published at Amsterdam in 1652. This book fixes accurately the standard of the knowledge of South Africa possessed by Europeans in the year when Mr Van Riebeek landed. It professes to be a description of the country about the Cape of Good Hope, and was published by Jodocus Hondius,” maker of land and sea charts, whose name is a guarantee that all possible care was taken in the preparation of the work. The numerous authorities referred to in this early South African hand- book prove further that the compiler was not only well read, but that he spared no trouble to collect oral information from the officers of ships. And yet he knew absolutely nothing of any part of the country now comprised in the Cape Colony except the sea coast from St Helena Bay to Mossel Bay, and even that very imperfectly. Elizabeth and Cornelia or Dassen and Robben Islands he describes accurately, but of Saldanha Bay he could give no other information than the name and position. Table Bay and the country a few miles around he could delineate with precision, as he had information from persons who had been shipwrecked and had lived here for many months. That there was such a river as the Camissa he had no doubt, but he believed it to be an open question if it did not enter the sea much further eastward than Linschoten had placed its mouth. To the natives in the neighbourhood of the Cape he gives both the names Hottentots and Caffres, and says they were called Hottentots on account of their manner of speaking, Caffres from their being held to have no religion. Their personal appearance, filthy habits, manner of subsistence, clothing, weapons, and huts are fairly described, but the writer had no idea that they were a distinct race from those living on the east coast. He thought it probable, indeed, that they were degraded offshoots from the empire of Monomotapa. This was the extent of the knowledge of South Africa possessed by Europeans a century and a half after the Portuguese discovered the sea route to India. Grandson of the world renowned map maker of the same name.

Saar, Johan Jacobsz: Reisbeschryving naar Oost Indien. Translated from the original German, and published at Amsterdam in 1672. The author, a native of Nuremberg, was in the service of the East India Company from 1644 to 1660, When returning to Europe with the homeward bound fleet of the last named year, he visited Table Bay. In a pamphlet of eighty- eight pages he has given four to the Cape, but there is nothing of very much interest in them except an account of the conspiracy to seize the Erasmus, and this is more completely recorded in manuscripts in the Cape Archives.

Schouten, Wouter: Reys Togten naar en door Oost Indien. The second edition was published at Amsterdam in 1708, the fourth, large quarto with plates, in 1780. The author, who was in the service of the East India Company, called at the Cape on his outward passage in 1658. Of this visit he gives a short, but interesting account. When returning home in 1665 he was here for six weeks. He devotes a chapter to the observations which he made at this time, in which he describes the colonists and the natives, as well as the condition of the settlement. The book is well written, and the chapter upon the Cape is not the least valuable portion of it, though it contains no information which not also to be gathered in a more perfect form from the official records of the period.

Evertsen, Volkert: Beschrijving der Reisen naar Oost Indien van. Translated from the original German, and published at Amsterdam in 1670. The author was a German who entered into the service of the East India Company in 1655, and proceeded as a midshipman to Batavia. In the outward passage and again when returning to Europe in 1667 he called at the Cape. On the last occasion he remained here a month. His work is a pamphlet of forty pages only, but his account of the condition of the infant colony, though very short, is highly interesting.

van Overbeke, Aernout: Bym Werken. The copy in my possession is of the tenth edition, published at Amsterdam it. 1719. The seventh edition was issued in 1699. The author was the same officer who first purchased territory from Hottentot chiefs in South Africa. Some of the verses are written with spirit, but there is nothing in the book to give it an enduring place among the works of the Dutch poets. The volume contains also in prose a Geestige en vermakelijke Reys Beschrijving van Mr Aernout van Overbeke, naar Oost Indien uytgevaren voor Raet van Justitie. in den jare 1668. This is a comic description of a sea voyage, and would be quite useless for historical purposes, if it were not for the mention that is made of Commander Van Quaelberg. The character of that Commander is delineated therein identically the same as I found it to be from his writings. Mr Van Overbeke adds that even the Hottentots regarded him with aversion.

Dapper, Dr 0: Naukeurige Besehrijvinge der Afrikaensche Gewesten, &c. Amsterdam, 1668. This is a splendidly printed and illustrated volume of eight hundred and fifty large pages, and contains a great number of maps and plans. It was carefully compiled from the best sources of information. As far as the Cape settlement is concerned, Dapper states that his descriptions are principally from documents forwarded to him by a certain diligent observer in South Africa, to which he has added but little from books of travel. The twenty-nine pages which are devoted to this country and its people were prepared by some one who was not here at the commencement of the occupation, who had not access to official papers, but who had been in the settlement long enough to know all about it, and who was studying the customs, manners, and language of the natives. Such a man was George Frederick Wreede, who was probably the writer. The order of events is not given exactly in accordance with official documents, though there is generally an agreement between them.

Ogilby, John: Africa, being an Accurate Description of, &c. Collected and translated from most Authentick Authors. London, 1670. All the information of value in this large volume is obtained from Dapper, to whom the compiler acknowledges his indebtedness. It is, indeed, almost a literal translation of Dapper’s work, and contains most of his maps and plates. An extract will show how little was then known of the people we call Kaffirs :-” The Cabona’s are a very black People, with Hair that hangs down their Backs to the Ground. These are such inhumane Cannibals, that if they can get any Men, they broyl them alive, and eat them up. They have some Cattel, and plant Calbasses, with which they sustain themselves. They have, by report of the Hottentots, rare Portraitures, which they find in the Mountains, and other Rarities: But by reason of their distance and barbarous qualities, the Whites have never had any converse with them.”

ten Rhyne, Wilhelm: Schediasma de Promontorio Bonae Spei, &c. Schaffhausen, 1686. This little volume of seventy-six pages in the Latin language is the work of a medical man in the service of the East India Company, who visited the Cape in 1673. It consists of a geographical description of the country in the neighbourhood of Table Bay, and a very interesting account of the Hottentots. The author obtained his knowledge of the customs of these people from careful observation and from information supplied by a native woman in the settlement who spoke the Dutch language.

de Neyn, Pieter: Lusthof der Huwelyken, bebelsende verscheyde seldsame ceremonien en plechtigheden, die voor desen by verscheyde Natien en Volckeren soo in Asia, Europa, Africa, als America in gebruik zyn geweest, als wel die voor meerendeel noch hedendaegs gebruykt ende onderhouden werden; mitsgaders desselfs Vrolycke Uyren, uyt verscheyde soorten van Mengel-Dichten bestaande.

Amsterdam, 1697. The author of this book held the office of Fiscal at the Cape of Good Hope from February 1672 to October 1674. He states that he had prepared a description of the Cape and had kept a journal, but that upon his return to Europe he was robbed of the whole of his papers and letters. The Lusthof der Huwelyken is a treatise upon the marriage customs of various nations, and is compiled from the writings of numerous authors. The Vrolyke Uyren are scraps of poetry of no particular merit. Among them are several referring to South Africa. In the Lusthof der Huwelyken are eight or ten pages of original matter concerning the Hottentots, written from memory. The story of the murder of the burghers by Gonnema’s people in June 1673 is told, but not very correctly. An account of the execution in the following August of the four Hottentot prisoners is given, which agrees with the records, and is even more complete in its details. The story of the rescue of the Hottentot infant by Dutch women in the time of Commander Borghorst is also told more fully than in the journal of the fort. The names of the women are given, and it is added that one of them afterwards became the wife of Johannes Pretorius, who had been a fellow student with the writer at Leiden. It is also stated that the child was baptized, but died shortly afterwards. Several other items of information are given in these few pages more fully than elsewhere.

Tachard, Guy: Voyage de Siam des Peres Jesuites, Envoyez par le Roy aux Indes á la Chine, avec leurs Observations Astronomiques, et leurs Remarques de Phisique, de Geographic, d’ Hydrographie, & d’ Histoire. Paris, 1686. ( Par ordre exprez de sa Majesté .) Father Tachard was one of a party of six Jesuit missionaries, who accompanied an embassy sent by Louis XIV to the Court of Siam. The embassy arrived at the Cape in June 1685, and remained here for about a week. Some of the missionaries were astronomers, who were provided with the best instruments known in their day, including a telescope twelve feet in length. The High Commissioner Van Rheede tot Drakenstein, whom they found in supreme command, placed at their disposal the pleasure house in the Company’s garden, which they converted into an Observatory. They found the variation of the magnetic needle to be eleven degrees and thirty minutes west. From observations of the first satellite of Jupiter, they calculated the difference of time between Paris and the Cape to be one hour twelve minutes and forty seconds, from which they placed the Cape in longitude forty “degrees thirty minutes east of Ferro. During the time that some of the missionaries were engaged in making astronomical observations, others were employed in investigating the natural history of the country and the customs of its native inhabitants. They made the acquaintance of a physician and naturalist named Claudius, a native of Breslau in Silesia, who was here in the service of the East India Company, and who had been with several exploring expeditions in South Africa. From him and from the Commander Van der Stel they obtained a great deal of information, to which they added as much as came under their own notice. The missionaries found a good many people of their own creed in the colony, both among the slaves and the servants of the Company, but though no one was questioned as to his religion, they were not permitted to celebrate the Mass on shore. Father Tachard speaks in unqualified terms of the very cordial reception which the members of the embassy had at the Cape. They were astonished as well as gratified, he says, to meet with so much politeness and kindness from the officers of the government. On his return to Europe in the following year he called again, and was equally well received. He devotes about fifty pages of his very interesting book to South Africa, and gives several illustrations of natives, animals, &c.

Cowley, Captain: A Voyage round the Globe, made by the Author in the years 1683 to 1686. London, 1687. With several editions subsequently. The writer was in Table Bay for about a fortnight in June 1686. His work is a pamphlet of forty-four pages, six of which are devoted to an account of what he saw at the Cape of Good Hope. He has managed to compress a good deal of information into a very small compass.

de Graaff, Nicolaus: Reisen na de vier Gedeeltens des Werelds Hoorn, 1701. The author of this very interesting book was a surgeon, and in that capacity visited various parts of the world between the years 1639 and 1688. He was in Table Bay in 1640, 1669, 1672, 1676, 1679, 1683, and 1687. His observations upon occurrences at the Cape are entirely in accordance with the documents preserved in the archives. His calculations of heights are more accurate than those of any other early traveller. In 1679 he estimated the height of Table Mountain from his measurements at 3,578 Rhynland feet. He speaks at the same time of the Duivelsberg by this name. The book is admirably written, but contains no information of value that is not also to be found in the government records of the time.

Dampier, William: A new Voyage round the World, &c. The second edition in two volumes was published at London in 1697. The work was translated into Dutch, and a beautiful edition was issued at Amsterdam in 1717. In these volumes Dampier gives a very interesting account of his adventures between his departure from England in 1679 and his return in 1691. He was at the Cape for six weeks in April and May 1691, and fifteen pages of his first volume are taken up with an account of this visit. Four pages of an appendix to the second volume are devoted to an account of Natal, as furnished to the writer by his friend Captain Rogers, who had been there several times.

Moodie, D.: The Record ; or a Series of Official Papers relative to the Condition and Treatment of the Native Tribes of South Africa. Compiled, translated, and edited by D. Moodie, Lieut. R. N., and late Protector of Slaves for the Eastern Division of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope. Cape Town, 1838. This work, now unfortunately so rare that a copy is only obtainable by chance, is a literal translation of a great number of original documents relating to the native tribes of South Africa from 1651 to June 1690, and from 1769 to 1809. A vast amount of labour and patience must have been expended in the preparation of this large and valuable book. I have not had occasion to make use of it because, first, the early records are now much more complete than they were when Mr Moodie examined them, and secondly, my aim was to collect information concerning the colonists as well as the natives. Nevertheless, it would be an act of injustice on my part not to acknowledge the eminent service performed by Mr Moodie in this field of literary labour forty years before the archives were entrusted to my care.

Lauts, G.: Geschiedenis van de Kaap de Goede Hoop, Nederlaansche Volkplanting. 1652-1806. Door den Hoogleeraar G. Lauts. Amsterdam, 1854. A pamphlet of 186 pages. The author had access to the Archives of South Africa at the Hague, and made good use of them. He was unacquainted with the country, and has made some very strange blunders, but his work as far as it goes is superior to anything previously produced in the colony.

de Jonge, J. K. J.: De Opkomst van het Nederlansch Gezag in Oost Indie. Verzameling van onuitgegeven Stukken uit het oud- koloniaal Archief. Uitgegeven en bewerkt door Jhr. Hr. J. K. J. de Jonge. The Hague and Amsterdam. The first part of this valuable history was published in 1862, the second part in 1864, and the third part in 1865. These three volumes embrace the general history of Dutch intercourse with the East Indies from 1595 to 1610. They contain accounts of the several early trading associations, of the voyages and successes of the fleets sent out, of the events which led to the establishment by the States General of the great Chartered East India Company, and of the progress of the Company until the appointment of Peter Both as first Governor General.

Rather more than half of the work is composed of copies of original documents of interest. The fourth part, published in 1869, is devoted to Java, and with it a particular account of the Eastern Possessions is commenced. The history was carried on as far as the tenth volume, which was published in 1878, but the work was unfinished at the time of the author’s death in 1880.

van Kampen, N. G.: Geschiedenis der Nederlanders buiten Europa. This is a work published in 4 octavo volumes at Haarlem in 1831. The references to the Cape Colony are incorrect, both as to occurrences and dates.

Source: Chronicles of the Cape Commanders by George McCall Theal – 1882