The History of Photography at the Cape

Cc

The camera obscura, an apparatus for tracing images on paper, was in common use by the 18th century as an aid to sketching. The earliest attempts to fix the images by chemical means were made in France by the Niépce brothers in I793, and in England by Thomas Wedgwood, an amateur scientist, at about the same time. Early in the 19th century further progress toward the invention of photography was being made simultaneously in France, England, Germany and Switzerland.

Of significance to photography in South Africa are the achievements of the English astronomer and scientist Sir John Herschel, who resided at the Cape from 1834 to 1838. It is thought that his experiments in connection with the development of photography advanced considerably while he lived at Feldhausen in Claremont, near Cape Town. In March 1839, only a year after his return to England, he revealed to the Royal Society the method of taking photographic pictures on paper sensitised with carbonate of silver and fixed with hyposulphite of soda. These discoveries had been accomplished independently of W. H. Fox Talbot, whose paper negative process (calotype, later called talbotype) became the basis of modern photography, and Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, whose process (daguerreotype) resulted in a positive photographic image being produced by mercury vapour on a silvered copper plate.

It is generally acknowledged that Herschel was the first to apply the terms ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ to photographic images and to use the word ‘photography’. He was also the first to imprint photographic images on glass prepared by coating with a sensitised film. Daguerre’s invention, announced in Paris in 1839, was slow in reaching the Cape; and although apparatus was advertised for sale in 1843, there is no evidence of photographs taken before 1845. The earliest extant photograph in South Africa was taken in 1845 by a Frenchman, E. Thiesson, who had photographed Daguerre himself the year before. The first portrait studio was opened in Port Elizabeth in Oct. 1846 when Jules Leger, a French daguerreotypist, arrived there from Mauritius. He took ‘photographic likenesses (a minute’s attendance)’ in a private apartment in Ring’s library, proceeding within a month to Uitenhage and Grahamstown. Leger left the country the following year, but not before his former pupil and assistant, William Ring, had succeeded him in the new art.

In Cape Town the first professional daguerreotype portraits were taken outdoors in December 1846 by the architect Carel Sparmann, at ‘all hours of the day and according to the latest improvements made in the art by himself’. He advised ladies to wear dark dresses in silk or satin, or Scotch plaid, the plaid being a pattern which showed itself with great exactness. Concerning gentlemen, the less there was of white in their clothing the greater the effect.

Daguerreotypes, usually about 5 x 8 cm in size, were bound up with a gilt mat and cover-glass to protect their fragile surfaces before being placed in velvet-lined case. The image was clearly defined, but the silver plate was costly and early Cape daguerreotypists often went bankrupt. Nevertheless they persevered in their portraiture and, to a much lesser extent, in taking views of buildings and street scenes, which were not generally for public sale until the 1800′s. Landscapes, pictorial subjects, and the early ‘news’ types of photography were at first more often the province of enthusiastic amateurs. The artisan-missionary James Cameron was experimenting with the calotype process for outdoor work before 1848, the paper negative being characterised by broad effects of light and shade. His photographs of the Anti-Convict Agitation meetings (1849) in Cape Town are the earliest known outdoor events in the Cape recorded by the camera and served as a basis for engravings made by the artist-photographer William Syme. Other early amateurs were William Groom, whose hand-coloured photograph of Wale Street, Cape Town (1852) is the earliest outdoor photograph extant in South Africa; Michael Crowly, who recorded the large number of wrecks in Table Bay (1857); and William Millard, who took the first panoramic view of Cape Town from Signal Hill (1859).

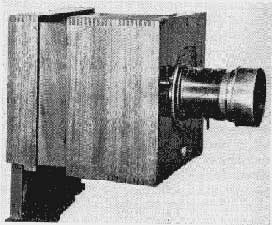

"oldest camera" in South Africa, brought to the Cape by Otto Mehliss of the German Legion (Photographic Museum, Johannesburg)

Scott Archer’s collodion process, introduced in the Cape in 1854, enabled prints to be made on sensitised paper from a collodion glass negative, resulting in a clearer rendering of half-tones. In field work the technique was particularly cumbersome as the plates had to be prepared on the spot and processed while still wet, necessitating the use of a portable dark-room such as a wagon, cart or tent. For all that, photography flourished during the collodion period, which lasted in the Cape until 1880 when James Bruton introduced the dry plate. Collodion portraits on glass (glass positives or ambrotypes) are sometimes confused with daguerreotypes, as they were made in the same sizes and fitted into similar cases. While the image of the glass positive is dull in appearance and can be seen at any angle, the daguerreotype has a shimmering, mirror-like reflecting surface which prevents the image being seen from every angle. For dating purposes professional daguerreotypy was practised in the Cape from 1846 to 1860, and glass positives were taken from 1854 until well into the 1870′s, although they were less in demand after the introduction of the carte-de-visite, a type of photograph, in 1861.

The art potential of photography was brought to public attention in 1888 at the third Fine Arts Exhibition in Cape Town. In addition to local contributions from professional and amateur photographers, there were importations from abroad. The first important use of photography for documentary purposes was achieved by William Syme and Frederick York when they published their portfolios of photographs of works of art displayed at this exhibition. No copy of either publication has as yet been traced. Earlier in the year the first general display of photographs had been held at the Grahamstown Fine Arts Exhibition, one of the organisers being the amateur photographer Dr. W. G. Atherstone, who had been present in Paris when Daguerre’s process was made public on 18 August 1839.

At the Paris Universal Exhibition in 1867 he exhibited photographs of Eastern Cape scenery, together with photographs illustrative of South African sport and travel by the explorer James Chapman, a pioneer well known for his impressive photographs of the Zambezi Expedition, which were on view at the South African Museum in 1862. An account of this expedition is given in Thomas Baines’s diary. He recounts how the photographer’s efforts were hampered in countless ways.

In the Eastern Province the majority of photographers had no fixed establishments, moving from town to town and serving a small population. Not many were as enterprising as the general dealer Henry Selby, who opened a studio in Port Elizabeth in 1854 and a branch at Uitenhage in 1855. Practising the daguerreotype, collodion and talbotype processes, he introduced stereoscopic portraits and vitrotypes (a process of producing burnt-in photographs on glass or ceramic ware), sold photographic materials and was also the first to sell views of Port Elizabeth (1856). With his partner James Hall he erected the first glass-house in the Eastern Cape (1857). This was a small wooden building with a roof consisting mainly of glass skylights and a number of panes of glass in its walls. Providing sufficient light for indoor portraiture and easily dismantled, it was especially useful to itinerant photographers. A drawback was the harsh glare of light, which irritated sitters, but more pleasing pictures were obtained by several Grahamstown photographers when they erected blue glass-houses in 1858. Arthur Green draped his with curtains.

Further progress was made in1858 with the coming of portraits on leather, card, silk, calico and oilskin. Likenesses first taken on glass and then transferred to leather won public favour immediately. They could be handled without risk of damage and could be sent overseas in a letter without additional postage charge. Documentary records of events were much in demand during Prince Alfred’s visit to South Africa in 1860. On tour he was officially accompanied by Cape Town’s leading photographer, Frederick York. The volume The progress of Prince Alfred through South Africa (Cape Town, 1861) contains seven photographs, the work of York, Joseph Kirkman and Arthur Green, whose view of Grahamstown in 1860 is the earliest known photograph of that city. These photographs were pasted in by hand. A gift of Cape views to the Prince by the Rev. W. Curtis was published in London in 1868, the Royal Edinburgh album of Cape photographs being the first major photographic work dealing exclusively with Cape scenery. Only two copies have been traced. In the 1860′s original photographs – including portraits of prominent men – were pasted in the Cape Monthly Magazine, the Eastern Province Magazine and Port Elizabeth Miscellany and the Cape Farmers’ Magazine. Several photographers, including F. York, J. Kirkman, J. E. Bruton and Arthur Green, undertook this.

Visiting Card Portrait

The introduction of the inexpensive carte-de-visite (visiting-card portrait) brought photography within reach of the masses. This new format (about 10 x 6 cm), first advertised at the Cape in 1861 at a guinea a dozen, provided the incentive for large numbers of new photographers to try their luck, often with disastrous results in smaller centres where available equipment was unsatisfactory.

The introduction of the inexpensive carte-de-visite (visiting-card portrait) brought photography within reach of the masses. This new format (about 10 x 6 cm), first advertised at the Cape in 1861 at a guinea a dozen, provided the incentive for large numbers of new photographers to try their luck, often with disastrous results in smaller centres where available equipment was unsatisfactory.

Macomo and his chief wife – attributed to William Moore South Africa, late nineteenth century 10.4 x 6.3 cm (including margins) inscribed on reverse with the title. With kind permission Michael Stevenson For more information contact +27 (0)21 461 2575 or fax +27 (0)21 421 2578 or email [email protected].

Other styles which made their appearance before 1870 were the alabastrine process (1861), an improvement on the quality of glass positives, the sennotype (1864), a chemical method of colouring photographs, and the wothly-type (1865), a specially prepared printing – out paper to increase the permanence of the photographic print.

Portrait of a woman, possibly a Cape Muslim, wearing headscarf Samuel Baylis Barnard. South Africa, late nineteenth century 10 x 6.1 cm (including margins), printed below and on reverse with photographer’s details; printed label on reverse reads: ‘From Crewes & Sons, Watchmakers & Jewellers. Cape Town.

Great strides were made toward perfecting photography between 1870 and 1880, commencing with the recording of scenes on the diamond-fields. Panoramic views of the diggings taken in 1870 by Charles Hamilton and William Roe, as well as stereoscopic views of Colesberg Kopje and camp life taken in 1872 by H. Gros, were among many that aroused interest. R. W. Murray’s The Diamond Field keepsake for 1873, a memento of photographs and letterpress sketches, was the forerunner of several albums of South African scenery first issued for publicity purposes.

The Cape landscapes of F. Hodgson, W. H. Hermann and J. E. Bruton and the published photographs of S. B. Barnard and G. Ashley are excellent examples of the high quality attained during that decade. An outstanding contribution was made by Bruton in 1874 when he recorded the transit of the planet Venus across the disc of the sun, under the direction of E. J. Stone, Astronomer Royal at the Cape.

First – class cameras and studios of increasing dimensions also provided greater facilities for portraiture, permitting large groups to be placed with ease and individuals to pose against elaborate background objects to form a pleasant picture. Few homes were without the Victorian album especially designed to present ‘cartes’ and the larger,’but not immediately as popular, cabinet portrait (approx. 15 x 10 cm) which had made its appearance at the Cape in 1867. This style was in general use from the eighties and, like the ‘carte’, remained fashionable well into the 20th century.

Sir David Gill and Charles Piazzi Smythe, astronomers at the Royal Observatory, Cape Town, made use of photography in their scientific work, Gill being the first to make a plan for a map of the sky (1882), assisted by Allis, a Mowbray photographer; and the Cape photographic Durchmusterung was produced as a pioneering venture. Smythe left South Africa after a sojourn of eight years.

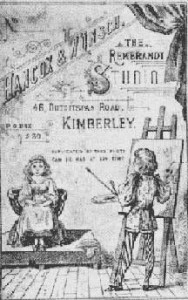

The Cape Town Photographic Club mentions in 1891 that a cart was necessary for club outings in order to transport the cameras. The first meeting of that club was held on 30 October 1890 and it is the oldest photographic society in the country that has been in continuous existence. However, the Kimberley club was older, having been founded six months earlier and so being the first in the Southern Hemisphere. Amateur photographers in Port Elizabeth held their first meeting in July 1891. These three clubs were followed by others at Grahamstown, King William’s Town and Johannesburg, while before 1900 others were established at Cradock, Pietermaritzburg, Oudtshoorn, Mossel Bay, and in addition one at the South African College in Cape Town. The early pioneers of professional and commercial photography faced many difficulties and many of them were itinerant and studio photographers, of whom in the 19th century there were over 500 in the country.

In the 196os there were about 180 photographic clubs between Nairobi and the Cape, with some 5000 members, as well as tens of thousands of still and ciné photographers throughout the country.

The Second Anglo-Boer War saw the early use of X-rays, the first recorded demonstration in South Africa having been carried out by the Port Elizabeth Amateur Photographic Society in the presence of medical doctors. K. H. Gould constructed the first X-ray camera in South Africa only a year after Röntgen’s discoveries, and it was put to use when a bullet had to be extracted from Gen. Piet Cronjé’s body. Although the ciné camera was used to give an illustrated record of war scenes in the Spanish-American War in Cuba in 1898, the Second Anglo-Boer War was much more extensively covered by it in the hands of special correspondents. The British Motoscope and Biograph Co. sent out their chief technician, Laurie Dickson, with an experienced staff on 14 October 1899 on the Dunuottar Castle, on which Winston Churchill and Gen. Sir Redvers Buller also travelled. Joseph Rosenthal, Edgar M. Hyman and Sidney Goldman followed on the Arundel Castle on 2 December as representatives of the Warwick Trading Co. Tens of thousands of photographs were produced during the war, many being published in magazines and books throughout the world. The Second Anglo-Boer War could be considered to be the first war thus fully covered by still, stereo and cine photography.

G. Lindsay Johnson of Durban, an ophthalmologist, was a pioneer of colour photography, writing in the early 1900s two books on the subject, Photographic optics and colour photography and Photography in natural colour. In more recent years a pioneer in the field of applied photography has been K. G. Collender of Johannesburg, who was the inventor of mass miniature radiography, for which patents were filed in Pretoria in 1926-27, Collender thus preceding over-seas workers by several years. He was the first man in the world to produce miniature negatives of X-rays of the chest, the size of a postage stamp, with the same technique as used in full-size radiography. Collender later at the Witwatetsrand Native Labour Association in Johannesburg was capable of producing 800 miniature 70-mm films per hour, and the incredible feat has been accomplished that 3400 films were completed, together with radiological reports, in the brief space of one morning. It has been said that this plant is ten years ahead of any other in the world.

The London Society of Radiographers honoured Collender in 1962 with its honorary fellowship, the first South African so honoured.

In this space age South Africans continue to pioneer in new fields. H. W. Nicholls of Cape Town was probably the first man to photograph Sputnik I as it hurtled through space; and at Olifantsfontein in March 1958 a team of men took the first photograph of the U.S.A.’s original satellite in flight and has since recorded several other notable feats. W. S. Finsen of the State Observatory made headlines for South Africa in the field of astronomy with his unique colour photographs of Mars during its close approaches to the earth in 1954 and 1956.

Various photographers who were pioneers in their respective fields built up large collections of photographs and thus left behind them a great photographic heritage to posterity. Such photographic collections are, for example, the Arthur Elliott Collection, housed in the State Archives in Cape Town; the Duggan-Cronin Collection, in the Bantu Art Gallery in Kimberley; and the David Barnett Collection in Johannesburg. Outstanding, too, are the writings and lecture tours of Dr. A. D. Bensusan of Johannesburg, and his interpretation of various compositional structures: ‘division of fifths’ and ‘arrow-head composition’ as applied in photography, which in the U.S.A. bears the name of ‘Bensusan’s flying wedge’. He was responsible for the foundation in 1954 of the Photographic Society of South Africa and for the inauguration of its associate and fellowship qualifications. He was also the founder of the Photographic Museum and Library in Johannesburg.

Bibliography: A. D. Bemsusan Source: Standard Encylopedia of South Africa (copyright Naspers)