You are browsing the archive for Table Bay.

Wreck of the Teuton

June 4, 2010Foundering of the Teuton Wreck off Quoin Point

The RMS Teuton had sailed from Plymouth on August 6th, 1881 at 2pm and Madeira on August 10th, 1881 at 11pm. She arrived in Cape Town on August 29th, 1881 at 6am. After leaving Table Bay on the evening of August 30th she struck an object off Quoin Point, between Danger Point and Cape Agulhas, on the south coast of South Africa at about 7:30 in the evening.

Over 200 lives lost

SIMON’S BAY, August 31, 9 o’clock p.m. Since the wreck of the Birkenhead, no such appalling loss of life by shipwreck as that of the Teuton has been known along the shores of South Africa. I have taken the utmost care to get at the truth, but no single narrative could yet be written which would be strictly accurate. I deem it best, therefore, to give you several stories as they were taken down from the lips of the survivors. The Quartermaster who was on the bridge with the captain declines to say anything until he is examined by the proper officials, but it is questionable if his evidence will throw any new light beyond the narratives unreservedly told by the others. The account given by Mr. Kromm is the most clear of any. He says that before they went down to dinner he was watching the coast, and thinking he had never been so close to it before. The Captain had a few minutes’ conversation with him, and strangely they talked of the wreck of the Waldenrian along that deceptive coast.

When the ship struck, the Captain only said, “Hallo!” and rushed on deck. Mr. Kromm’s story follows. How he escaped is one of those marvellous incidents which, until they occur, are deemed impossible. He could not swim a stroke; he was hampered with an overcoat, and yet he struggled and floated until he secured a bit of wreckage. His watch stopped at a quarter to eleven o’ clock, and from that fact he arrives at the exact moment when he jumped from off the poop of the ship into the water. The boatswain says that the boats hovered around the spot where the ship went down until daybreak. Mr. Kromm is quite clear that the boats commenced to move slowly – something like half an hour after, and he remarks there was nothing to remain for. The moonlight night enabled them to see around, and, with the exception of small wreckage, there was nothing floating about. The boatswain says he was on the forecastle half an hour before the ship struck, and he saw no land, and adds that perhaps he did not see it because it was not his duty to look out for it. He did not see land afterwards, because he had too much else to do.

The men are perhaps careful to be on their guard against carelessly saying something which may be misconstrued and cause trouble hereafter. Mr. Kromm is very clear and empathetic. His opinion is that the captain, confident in the fact that his ship having watertight compartments held on too long, and that when they gave way, it was too late to save the passengers. He points out that the ship had been settling down by her head from the time she struck, and if after the first hour the passengers had been placed in the boats they could have been towed until the necessity for the ship’s abandonment became evident. The order on board is said to have been admirable. There was not an order given which was not obeyed. Mr. Kromm bears out the boatswain, who says that a few minutes before the ship took her final plunge, there was no water in the engine-room. The captain is said only to have left the bridge when it gave way. I am not so certain that the bridge was carried away, for if it had been it would most probably have been floating with the wreckage.

It is certain the captain did not leave the bridge until the steamer was certainly foundering. He probably left it when the watertight compartments gave way, and the rush of water into the ship decided her fate. The Teuton had six compartments. The bow compartment is said to have been dry, and it is thought that the ship must have struck on the port side of the second compartment, and the noise after the striking was a ripping, tearing noise as if the plates were being torn asunder. The carpenter and the boatswain were both on board the ship when she went down, but I cannot find there is any truth in the story of the captain being seen in the water. There are of course some heartrending stories, and they are simply told – shorn of all elaboration – in what follows. That of Miss Ross is a very touching one, and perhaps all the more so because of the belief that her parents are not drowned. I must not trespass longer on the skill of the telegraph clerks who have so courteously assisted me tonight; and I must not forget on behalf of the survivors to thank the good people of Simon’s Town for all their hospitality and kindness, and …….yet a ward or two about poor Manning, – one of the most unassuming, most careful, and kindly skippers that ever trod a ship’s deck. How is it that such an unkind fate overtook him? And the gallant fellows who officered the ship and maintained that discipline and order for which the Union Company is famous – how is it that they were not instrumental in saving more life? Can we yet say that all hope of other survivors reaching land must be given up? If, however, no more than those who have landed at Simon’s Bay live to tell the story, I am much inclined to think that the foundering of the Teuton will remain for all time as one of the saddest and most strangely unaccounted for of the mysteries of the sea.

The Stories of the Survivors

SIMON’S TOWN, Wednesday evening, 9 P.M. – Mr. Kromm says : – “We left Table Bay with a light S.E. wind, shortly after 10 o’clock on Tuesday morning. Nothing occurred worthy of mentioning until we came off Quoin Point. The evening was beautifully fine. The moon was overhead; the stars were shining; and there was not the slightest sign of fog or vapour. We could make out the land line perfectly, and could see even the sandy shore, which did not appear to me to be more than a mile distant. Suddenly the ship struck without any warning whatever. I do not know who the officer was on watch. It was not the chief officer, for he was sitting with me at the table.

We were just finishing dinner, and were sipping coffee. The captain had the cup of coffee in his hand, and it was shaken out of his hold, so violent was the concussion. The whole table was swept of glass and dinner-ware, and fell on to the port side, which showed us that the ship had been struck on the port side. After striking she shivered, like an aspen leaf, and heeled over to port. There was some little confusion; the women shrieked, and there was a general rush on deck. The pumps were immediately sounded, and it was found that the fore-compartment was leaking. The order kept on deck was admirable, and officers and men vied in their efforts at soothing passengers.

The boats were slung out board, and they were all ready provisioned with biscuit and water within half an hour of the ship striking. The passengers were all ordered on the poop, and were told to sit quietly until they were ordered off to their respective boats. The doctor was in charge of the passengers on the poop. All this time the ship was settling down by the head gradually. Volunteers were called for from amongst the passengers for the pumps, and they assisted freely. After striking, the ship’s head was put round to the westward evidently with the hope of reaching Simon’s Bay. There was a little south-east wind with a little jobble of a sea on. It was between a quarter-past seven and half-past seven when the ship struck, and up till half-past ten the vessel kept on her way, and everything was orderly on board. At half-past ten the ship’s head was so down that her stern was out of water, and the screw was of little use. The Captain now gave orders for the starboard waist lifeboat to be lowered, and the women and children to be put in, which was done, the boat being lowered and the women and children handed into it. The ship was then hardly moving, for her propeller was out of water, and was no longer any use to her. The engines were stopped, and steam was gradually being blown off. The starboard quarter boat, which had already been lowered, was ordered alongside to receive passengers, and that was the first time I heard Captain Manning’s voice.

He said “Why don’t you hurry up and get the boat alongside”. He had no sooner the words out of his mouth when the ship gave a dip, and in less than a minute she appeared to make a somersault. I, seeing this, made a jump overboard at her port quarter. I could no swim, but I was fearful of being carried down by the suction, and I hoped to be picked up by the port quarter boat, which had been lowered some-while. I struggled about, and at last came across a teak-wood casing using for covering the iron bollards on the deck. I tried to get on to it, but it kept revolving, and it twice threw me away from it. I, at last, however, got a good grip of it in position and must, I should think, have held on to it from twenty minutes to half an hour. I then saw, at a short distance, one of the boats showing a light. My cries for help brought them to me in about five minutes, and I was taken into the carpenter’s boat. We succeeded in taking three men off a boat which was bottom up.

The other boat came alongside us and we divided passengers and ….. about, and picked up, I think, five people. We heard few cries. The bulk of passengers must have gone down in the ………. The bulk of the passengers were on the poop, when the ship went over, head down, the passengers must have been precipitated into water, and they must have gone down in suction. She went down like a streak of lightning. I would not have believed it possible that that vessel could have gone down so suddenly. There was a loud crashing of timber, an escape of steam, a wild rush of water, and the Teuton was out of sight. We only saw some wreckage float about. I fear – indeed, I am almost certain – that the boat with the women and children in it was fastened by a rope to the vessel or did not ……….. the vortex. The moonlight enabled us to see everything distinctly. We could not see anything of the boat with the women. We heard no cries, ………. after pulling around the spot for half-an-hour ………….. course of the two boats was made for Simon’s ……….., steering for the Cape of Good Hope. The boat crew pulled all night. The men were most orderly and well behaved, and did everything they could. Sail was got on the boat at daybreak. There was then a fresh breeze and an ugly jobble of ………. which compelled us to keep baling. We had double-reefed sail during the forenoon, but as the wind freshened another reef was taken in, and even then we found she had as much sail as ……….. could carry.

We got up to Cape Point, and were about five miles off from it at between, ……………… should say, eleven and twelve. We over…… ten or twelve miles in mistaking the entrance to Simon’s Bay, and but for this we should have been earlier in Simon’s Bay than we were. The carpenter’s boat, which was a better sailor than ours, and had made a direct run ………. the Bay, arrived there first. In fact, she ran out of our sight altogether. There were crowds of people on the wharf as we came up to it, and the greatest kindness was shown to us all. We had to be lifted out of the boats for we were so cramped with sitting and with cold that we could not move.

The boatswain states: “I had reported all the boats swung out to the chief officer, as usual, and we went below to get his dinner. I had hardly got to the forecastle when the ship struck. The pumps were sounded and set to work, but they could not keep the water down. All the boats were lowered and provisioned by 9 p.m., and everything ready to pass the passengers in which there was a sudden crash, and the ship immediately sank …. first. I was carried down by the ship, and ………….. rising caught hold of a spar, and was afterwards picked up by the carpenter’s boat. There was not the slightest confusion on board. The ship sunk most suddenly. I think the forward bulkhead must have given way. The last I saw of the captain was on the bridge, which, with the wheel-house, deck-house, and funnel, seemed to go at once. No one thought she would sink as fast as she did. We reached Simon’s Bay at about 2 p.m.”

Miss Ross says: – “I was in the cabin with my mother and father, getting the baby to sleep, when I heard a dull grating sound. Soon after that we were all called up to the deck, when the Doctor and Chief Officer told us there was no immediate danger, and that we were to be calm, as if the ship would sink the boat would save us. I and my mother and father were in the boat when I saw the ship sinking and we were capsized. I caught hold of a spar and afterwards of a barrel, and after floating a little was taken into the carpenter’s boat. A great number of spars were floating about, and I hope papa is saved – he was a powerful swimmer”.

The carpenter says the ship did not strike heavily, but appeared to have struck somewhere on the port side abaft her bow. For some time there was not a drop of water in the engine-room or ……….. compartments. At the time of sinking he was on the gangway platform, passing passengers to the boat which was capsized. The chief officer and supercargo were beside him. He heard the cry of the ship sinking, and before he could gain the deck he was carried below. He remembered no more until he found himself floating, and was pulled into a boat. He took command of the boat, and, with the boatswain’s boat, remained as near as he could judge on the scene until daybreak, but …… not see any trace of debris or hear any cries. At daybreak they saw high land, which they took for Cape Point, and steered in that direction. It turned out to be Hangklip…………

From our Special Correspondent.

From the Government Gazette August 1881

The first slave

August 6, 2009 The first slave, one Abraham, a stowaway from Batavia, reached Table Bay on the Malacca on 2 March 1653. He was made to work for the Company until sent back to Batavia three years later. In March 1655 there were three slaves, brought from Madagascar. Apart from these few, Cape slavery may be dated from the arrival on 25 March 1658 of the Amersfoort, with some 170 slaves taken off a Portuguese ship. Since Hottentots were unreliable, Van Riebeeck favoured the use of slave labour. He allowed free burghers to purchase slaves on credit at 50 to 100 guilders each, but most slaves remained in the employ of the Dutch East India Company. Burghers, finding that slaves deserted, returned those that were intractable to the Company, believing that they were not worth their keep.

The first slave, one Abraham, a stowaway from Batavia, reached Table Bay on the Malacca on 2 March 1653. He was made to work for the Company until sent back to Batavia three years later. In March 1655 there were three slaves, brought from Madagascar. Apart from these few, Cape slavery may be dated from the arrival on 25 March 1658 of the Amersfoort, with some 170 slaves taken off a Portuguese ship. Since Hottentots were unreliable, Van Riebeeck favoured the use of slave labour. He allowed free burghers to purchase slaves on credit at 50 to 100 guilders each, but most slaves remained in the employ of the Dutch East India Company. Burghers, finding that slaves deserted, returned those that were intractable to the Company, believing that they were not worth their keep.

William J. Morris

June 24, 2009Master Builder of Cape Town

William J. Morris was born on the 11th February 1826 in Oxon, England, and was employed by the Duke of Marlborough as a game keeper when he developed pulmonary tuberculosis during the severe winter of 1856. His doctor recommended that he move to a sunnier climate.

Not long after this William was accepted, together with his wife and three children, for the Sir George Grey Immigration Scheme. In screening the prospective applicants, there were some basic requirements: good health, sober habits, industrious, good moral character, and in the habit of working for wages (as promulgated by Act No. 8 of 1857). From these regulations it would seem that a person with T.B. would certainly not have been accepted, and as the gentleman in question lived to the grand age of 90, and certainly worked industriously on arrival in the Cape (not conducive to a sickly person) the circumstances appear to dispel such a legend.

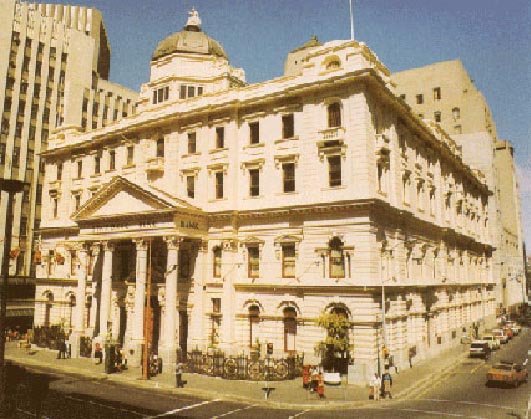

Standard Bank, Adderley Street

The journey to the Cape was aboard the vessel named “Edward Oliver” under the command of Master J. Baker. The ship departed from Birkenhead on 10th July 1858, and after 57 days at sea arrived in Table Bay on 5th September 1858. Little is known about the voyage excepting 14 deaths were recorded and seven births took place on board. Listed as the ships surgeon was Dr. Fred Johnson as well as trained teacher Mr. Tom Gibbs who were to care for the passenger’s health and education. It is possible that it was not a pleasant journey for the Morris family remembering that the three children Richard, Kate and William were still young and the latter being under twelve months of age.

The majority of the artisans and tradesmen had been fixed up with immediate employment, as there was a great demand for skilled and semi-skilled men for the new railway track being constructed from Cape Town to Wellington, as well as the harbour construction project in Table Bay.

Not long after Williams arrival he leased some land at the top end of Duke Road in Rondebosch, then a distant suburb of Cape Town, and very reminiscent of Wychwood Forest and his native Oxfordshire. This piece of land was developed into a market garden and the family lived in a nearby cottage.

It was whilst William J. Morris and family were living in Rondebosch that on 29 April 1862 their youngest son Benjamin Charles Morris was born and baptized in St. Paul’s Anglican Church in Rondebosch, whereby his father (William) declared his occupation as a “gardener” and place of residence as “Rouwkoop Road”, Rondebosch. Click here to search these church records.

Benjamin Charles Morris's Baptism Record

Richard H. Morris was still a growing boy of just 8 years old. By the age of 14 years and still living in Rondebosch, he was indentured to Alexander Bain, a shipbuilder/shipwright of 17 Chiappini Street, Cape Town as an apprentice carpenter/shipwright.

Although the new suburban railway from Cape Town to Wynberg had been opened to the public in 1865, Richard was obliged to walk from Rondebosch to the North Wharf in Dock Road, Cape Town as transport was too expensive for his meager earnings. However, he was soon organized in getting a “lift” from the coachman he befriended who worked for the governor of Rustenburg House. Richard secured his free lift on the footman’s place at the rear of the coach, where he would sit in reasonable comfort for the journey which took him to the Castle. Unfortunately this mode of travel did not operate for the return journey home, nor did it operate during the winter months, so Richard just had to “jog”.

It would appear that the last train from Cape Town to Wynberg in the afternoons was scheduled for departure from the city at 5pm, but needless to say as an apprentice, Richard was still working at the shipyard. Despite the arduous circumstances of his youth, the enforced exercise proved most beneficial a few years later when he entered into competitive sport i.e. race rowing, especially as Richard was just over 5ft. tall and weighed less than 60 kilos.

During 1870, the Bain’s Shipyard was taken over by Mr. Christopher Robertson, as specialist in sailing ships and wooden masts, and as Richard was learning his trade with three other young apprentices, he was taught the art of shaping a sailing vessel’s mast with the hand spokeshave. The firm from then on was known as “Robertson & Bain” which continued operating in Dock Road, Cape Town for several decades, specializing in the supply of wooden masts for sea-going sailing ships.

Before carrying on with the life story of Richard H. Morris it is important to mention that the Anglican Church of St. Johns on the corner of Long and Waterkant Street had been built in 1856. It was at this church that during the 1860′s Richard became a choir boy and in 1872 a Sunday School Teacher.

In 1876 the Templar rowing club started in Cape Town where Richard and his brother were both members and enthusiastic oarsmen.

The christening of the personally constructed fast rowing boat by Richard came as no surprise by the owners of Robertson and Bain. The name of the boat was called the “Alpha”.

In 1882 the construction of a row of cottages built by Wm. J. Morris and his brother Richard (father & son) was started in Upper Church and Longmarket Streets and were to be called “Lorne Cottages” in honour of the Lorne Rowing Club which was started in Cape Town in 1875 and named after the Scottish Firth near Island of Mull of Kintyre.

On Saturday 6th June 1885 Richard married Helen Ann Lyell in St. John’s church. The newly married couple went that day to “Lorne Cottages” to make their permanent home and raise a family.

Richard and Helen Ann Lyell's Marriage Certificate

Helen was in fact a little girl of ten years old when she first encountered Richard. That was when he was in his twenties and he was late for work and was running along the road when he accidentally knocked over a little girl. He tried to console her, and from this time onwards a very special friendship developed.

It was in the same church that Richard’s younger brother William John married Matilda Jane Altree on 25th August 1886 and a younger brother married in St. Paul’s in Rondebosch on 14th September 1887. It is interesting to note that St. John’s Church was deconsecrated after the last evening service in June 1970 as the ground and building was sold, after much pressure from business interests, for an astronomical amount, and the church was completely demolished to make way for the present modern commercial complex known as “St. Johns Place”. Click here to search these church records.

In 1884 Richard Morris as cox and his brother of the “Templar Club” had their first win as champions winning both “Maiden Oarsmen” and “Championship of Table Bay” events.

In June 1878 Richard H. Morris went into partnership with friend & neighbour Chas. Algar from Rondebosch, who had known the Morris family for quite some time. Little known to Chas was that Richard was to be the future brother-in-law to his sister Bertha Algar.

The first workshops of Algar and Morris were at 39 Shortmarket Street, Cape Town. (between Long and Loop Street ). But misfortune was the cause of the break-up of the working partnerships as the 30-year-old Chas Algar died suddenly on 4th October 1883.

Banking institutions were now playing a major role in the economy of the country and in 1883 Richard Morris landed the contract to build the Standard Bank in Adderley Street for the amount of £32,000 – the two storied building was designed in neo-classical style by Charles Freeman. Two additional floors were added on by Morris in 1921.

Richard made a repeat performance in May 1885 wining the 2 mile race in 15 minutes and 55 seconds.

March 1886 saw the arrival of Richard and his wife Helen’s daughter Kate as well as Richard wining the “Champion of Table Bay” for the third consecutive year.

Eleven years after the death of Chas Algar, Richard Morris secured the construction contract for the new City Club in Queen Victoria Street for a sum of £22,000.

Between the years of 1888 and 1895 Helen Morris gave birth to Edith, Bertha and William Henry Morris, the only son to Richard.

By 1896 Richard H. Morris had become known as a builder of distinguished quality and workmanship and the fame of R.H. Morris had spread. Herbert Baker had met Richard on several occasions and took immediately to this man who built with such fine quality and precision. It was then that R.H. Morris secured the prestige contract for the restoration of “Groote Schuur”, after the building had been extensively destroyed by fire.

Richard H. Morris by 1899 had workshops in both 52 Rose Street and 173 Longmarket Street. In 1902 Frank Lardner joined the staff of R.H. Morris and in 1911 he became the manager.

Father, William James Morris, died at the old age of ninety years on 22 March 1915. In 1919 the company of R. H. Morris (Pty) Ltd was officially formed to cope with the new lumber contract in Knysna. It was from this time onwards that R.H. Morris was renowned throughout Southern Africa for the excellent workmanship and quality in carpentry all starting from old Mr. Morris himself. School desks, church pews and altars were manufactured in their joinery shop for years to come. The items were delivered as far away as Botswana, Rhodesia, Zambia and Mozambique. Along with the desk and school equipment Morris ink wells and stands were also produced.

The Morris workshop also manufactured one of the very few original gramophones that were ever produced in South Africa and which was called a “melophone”. Many of these items can be seen on display in the Educational Museum in Aliwal Road, Wynberg today.

Sadness unfortunately halted joy when Richard and Helen Morris celebrated their Golden Wedding Anniversary on 6th June 1935 and then on 24 July Helen tragically passed away at home as well as Bertha, wife of Benjamin Morris, on the 6th December.

Richard at the age of 83 years old in 1936 retired from the construction industry and handed the reigns over to Frank Lardner. Frank ran the company until 1942 when he passed away. The business was then handed over to a young civil engineer, Clifford Harris. The existing premises of Rose and Longmarket Street were finally vacated when the furniture workshops and Building /Civil Engineering were consolidated and new premises built in Ndabeni.

In April 1949 Richard Henry Morris succumbed to natural causes and passed away at the age of 95 years and 5 months.

This was certainly not the end of an era for R.H. Morris Pty Ltd – as in 1952 the company was given financial backing for the New Municipal Market at Epping in Cape Town by the British Engineering giant Humphreys. The firm is no longer associated with the family. Later the company was taken over by the Fowler Group and is now in the hands of Group Five Construction who have retained the image of the name in perpetuating the fine record of the founder Richard Henry Morris.

Many of the other buildings in Cape Town which were either completed by or alterations were performed on, include the University of Cape Town, Diocesan College in Rondebosch, Music School at U.C.T. as well as many Sir Herbert Baker buildings.

In 1995 when much of this research was done I managed to find a second “melophone” and an original “Morris” desk for sale which ex-Managing Director Frank Wright was extremely grateful for me finding these wonderful company artifacts. Shortly before the final documents were found I also located the grand nephew of R.H. Morris who very kindly gave me the medal won by Richard in the “Championship of Table Bay”. This is now on display in the boardroom of Group Five Construction in Plum Park, Plumstead in the Cape.

Authors: Heather MacAlister and H.W Haddon

William J. Morris

June 15, 2009Master Builder of Cape TownWilliam J. Morris was born on the 11th February 1826 in Oxon, England, and was employed by the Duke of Marlborough as a game keeper when he developed pulmonary tuberculosis during the severe winter of 1856. His doctor recommended that he move to a sunnier climate.

Not long after this William was accepted, together with his wife and three children, for the Sir George Grey Immigration Scheme. In screening the prospective applicants, there were some basic requirements: good health, sober habits, industrious, good moral character, and in the habit of working for wages (as promulgated by Act No. 8 of 1857). From these regulations it would seem that a person with T.B. would certainly not have been accepted, and as the gentleman in question lived to the grand age of 90, and certainly worked industriously on arrival in the Cape (not conducive to a sickly person) the circumstances appear to dispel such a legend.

Standard Bank, Adderley Street

The journey to the Cape was aboard the vessel named “Edward Oliver” under the command of Master J. Baker. The ship departed from Birkenhead on 10th July 1858, and after 57 days at sea arrived in Table Bay on 5th September 1858. Little is known about the voyage excepting 14 deaths were recorded and seven births took place on board. Listed as the ships surgeon was Dr. Fred Johnson as well as trained teacher Mr. Tom Gibbs who were to care for the passenger’s health and education. It is possible that it was not a pleasant journey for the Morris family remembering that the three children Richard, Kate and William were still young and the latter being under twelve months of age.

The majority of the artisans and tradesmen had been fixed up with immediate employment, as there was a great demand for skilled and semi-skilled men for the new railway track being constructed from Cape Town to Wellington, as well as the harbour construction project in Table Bay.

Not long after Williams arrival he leased some land at the top end of Duke Road in Rondebosch, then a distant suburb of Cape Town, and very reminiscent of Wychwood Forest and his native Oxfordshire. This piece of land was developed into a market garden and the family lived in a nearby cottage.

It was whilst William J. Morris and family were living in Rondebosch that on 29 April 1862 their youngest son Benjamin Charles Morris was born and baptized in St. Paul’s Anglican Church in Rondebosch, whereby his father (William) declared his occupation as a “gardener” and place of residence as “Rouwkoop Road”, Rondebosch. Click here to search these church records.

Benjamin Charles Morris's Baptism Record

Richard H. Morris was still a growing boy of just 8 years old. By the age of 14 years and still living in Rondebosch, he was indentured to Alexander Bain, a shipbuilder/shipwright of 17 Chiappini Street, Cape Town as an apprentice carpenter/shipwright.

Although the new suburban railway from Cape Town to Wynberg had been opened to the public in 1865, Richard was obliged to walk from Rondebosch to the North Wharf in Dock Road, Cape Town as transport was too expensive for his meager earnings. However, he was soon organized in getting a “lift” from the coachman he befriended who worked for the governor of Rustenburg House. Richard secured his free lift on the footman’s place at the rear of the coach, where he would sit in reasonable comfort for the journey which took him to the Castle. Unfortunately this mode of travel did not operate for the return journey home, nor did it operate during the winter months, so Richard just had to “jog”.

It would appear that the last train from Cape Town to Wynberg in the afternoons was scheduled for departure from the city at 5pm, but needless to say as an apprentice, Richard was still working at the shipyard. Despite the arduous circumstances of his youth, the enforced exercise proved most beneficial a few years later when he entered into competitive sport i.e. race rowing, especially as Richard was just over 5ft. tall and weighed less than 60 kilos.

During 1870, the Bain’s Shipyard was taken over by Mr. Christopher Robertson, as specialist in sailing ships and wooden masts, and as Richard was learning his trade with three other young apprentices, he was taught the art of shaping a sailing vessel’s mast with the hand spokeshave. The firm from then on was known as “Robertson & Bain” which continued operating in Dock Road, Cape Town for several decades, specializing in the supply of wooden masts for sea-going sailing ships.

Before carrying on with the life story of Richard H. Morris it is important to mention that the Anglican Church of St. Johns on the corner of Long and Waterkant Street had been built in 1856. It was at this church that during the 1860′s Richard became a choir boy and in 1872 a Sunday School Teacher.

In 1876 the Templar rowing club started in Cape Town where Richard and his brother were both members and enthusiastic oarsmen.

The christening of the personally constructed fast rowing boat by Richard came as no surprise by the owners of Robertson and Bain. The name of the boat was called the “Alpha”.

In 1882 the construction of a row of cottages built by Wm. J. Morris and his brother Richard (father & son) was started in Upper Church and Longmarket Streets and were to be called “Lorne Cottages” in honour of the Lorne Rowing Club which was started in Cape Town in 1875 and named after the Scottish Firth near Island of Mull of Kintyre.

On Saturday 6th June 1885 Richard married Helen Ann Lyell in St. John’s church. The newly married couple went that day to “Lorne Cottages” to make their permanent home and raise a family.

Richard and Helen Ann Lyell's Marriage Certificate

Helen was in fact a little girl of ten years old when she first encountered Richard. That was when he was in his twenties and he was late for work and was running along the road when he accidentally knocked over a little girl. He tried to console her, and from this time onwards a very special friendship developed.

It was in the same church that Richard’s younger brother William John married Matilda Jane Altree on 25th August 1886 and a younger brother married in St. Paul’s in Rondebosch on 14th September 1887. It is interesting to note that St. John’s Church was deconsecrated after the last evening service in June 1970 as the ground and building was sold, after much pressure from business interests, for an astronomical amount, and the church was completely demolished to make way for the present modern commercial complex known as “St. Johns Place”. Click here to search these church records.

In 1884 Richard Morris as cox and his brother of the “Templar Club” had their first win as champions winning both “Maiden Oarsmen” and “Championship of Table Bay” events.

In June 1878 Richard H. Morris went into partnership with friend & neighbour Chas. Algar from Rondebosch, who had known the Morris family for quite some time. Little known to Chas was that Richard was to be the future brother-in-law to his sister Bertha Algar.

The first workshops of Algar and Morris were at 39 Shortmarket Street, Cape Town. (between Long and Loop Street ). But misfortune was the cause of the break-up of the working partnerships as the 30-year-old Chas Algar died suddenly on 4th October 1883.

Banking institutions were now playing a major role in the economy of the country and in 1883 Richard Morris landed the contract to build the Standard Bank in Adderley Street for the amount of £32,000 – the two storied building was designed in neo-classical style by Charles Freeman. Two additional floors were added on by Morris in 1921.

Richard made a repeat performance in May 1885 wining the 2 mile race in 15 minutes and 55 seconds.

March 1886 saw the arrival of Richard and his wife Helen’s daughter Kate as well as Richard wining the “Champion of Table Bay” for the third consecutive year.

Eleven years after the death of Chas Algar, Richard Morris secured the construction contract for the new City Club in Queen Victoria Street for a sum of £22,000.

Between the years of 1888 and 1895 Helen Morris gave birth to Edith, Bertha and William Henry Morris, the only son to Richard.

By 1896 Richard H. Morris had become known as a builder of distinguished quality and workmanship and the fame of R.H. Morris had spread. Herbert Baker had met Richard on several occasions and took immediately to this man who built with such fine quality and precision. It was then that R.H. Morris secured the prestige contract for the restoration of “Groote Schuur”, after the building had been extensively destroyed by fire.

Richard H. Morris by 1899 had workshops in both 52 Rose Street and 173 Longmarket Street. In 1902 Frank Lardner joined the staff of R.H. Morris and in 1911 he became the manager.

Father, William James Morris, died at the old age of ninety years on 22 March 1915. In 1919 the company of R. H. Morris (Pty) Ltd was officially formed to cope with the new lumber contract in Knysna. It was from this time onwards that R.H. Morris was renowned throughout Southern Africa for the excellent workmanship and quality in carpentry all starting from old Mr. Morris himself. School desks, church pews and altars were manufactured in their joinery shop for years to come. The items were delivered as far away as Botswana, Rhodesia, Zambia and Mozambique. Along with the desk and school equipment Morris ink wells and stands were also produced.

The Morris workshop also manufactured one of the very few original gramophones that were ever produced in South Africa and which was called a “melophone”. Many of these items can be seen on display in the Educational Museum in Aliwal Road, Wynberg today.

Sadness unfortunately halted joy when Richard and Helen Morris celebrated their Golden Wedding Anniversary on 6th June 1935 and then on 24 July Helen tragically passed away at home as well as Bertha, wife of Benjamin Morris, on the 6th December.

Richard at the age of 83 years old in 1936 retired from the construction industry and handed the reigns over to Frank Lardner. Frank ran the company until 1942 when he passed away. The business was then handed over to a young civil engineer, Clifford Harris. The existing premises of Rose and Longmarket Street were finally vacated when the furniture workshops and Building /Civil Engineering were consolidated and new premises built in Ndabeni.

In April 1949 Richard Henry Morris succumbed to natural causes and passed away at the age of 95 years and 5 months.

This was certainly not the end of an era for R.H. Morris Pty Ltd – as in 1952 the company was given financial backing for the New Municipal Market at Epping in Cape Town by the British Engineering giant Humphreys. The firm is no longer associated with the family. Later the company was taken over by the Fowler Group and is now in the hands of Group Five Construction who have retained the image of the name in perpetuating the fine record of the founder Richard Henry Morris.

Many of the other buildings in Cape Town which were either completed by or alterations were performed on, include the University of Cape Town, Diocesan College in Rondebosch, Music School at U.C.T. as well as many Sir Herbert Baker buildings.

In 1995 when much of this research was done I managed to find a second “melophone” and an original “Morris” desk for sale which ex-Managing Director Frank Wright was extremely grateful for me finding these wonderful company artifacts. Shortly before the final documents were found I also located the grand nephew of R.H. Morris who very kindly gave me the medal won by Richard in the “Championship of Table Bay”. This is now on display in the boardroom of Group Five Construction in Plum Park, Plumstead in the Cape.

Authors: Heather MacAlister and H.W Haddon

Eva (Krotoa) van die Kaap

June 9, 2009

Eva (Krotoa) van die Kaap

Krotoa was born at the Cape, circa 1642 – died Cape Town, 29th July 1674. A female Hottentot interpreter, Eva was a member of the Goringhaikona (Strandlopers or Beach-combers), a Hottentot tribe which lived in the vicinity of Table Bay. The captain of this tribe, Herry, was her uncle, and her sister was the wife of Oedasoa, captain of the Cochoqua (Saldanhars).

Shortly after their arrival at the Cape, Jan van Riebeeck and his wife took Eva into their home. They gave her a Western education and instructed her in the Christian religion. She soon learnt to speak Dutch fluently, and, later on, was able to make herself understood in Portuguese. Although she did not receive official payment for this, she was used as an interpreter, especially between V.O.C. officials and Oedasoa, with whom she sometimes went to stay.

Van Riebeeck had a high opinion of her ability as an interpreter, although later he warned his successor not to accept everything she said without reservations.

On the 3rd May 1662, Eva was baptized in the church inside the Fort of Good Hope by a visiting minister, the Rev. Petrus Sibelius, with the secunde, Roelof de Man and the sick comforter, Pieter van der Stael, as witnesses. She was also the first Hottentot to marry according to Western customs.

On the 26th April 1664, and with the permission of the Council of Policy, she was married in a civil ceremony to the explorer, Pieter van Meerhoff, and she received a dowry of fifty rix-dollars from the V.O.C. On the 2nd June 1664 the marriage was also solemnized in church. Of the children born from this marriage three survived.

In May 1665 Van Meerhoff and his family left the Cape when he was sent to Robben Island as commander. In 1667 he was murdered during an expedition to Madagascar and on 30 September 1668 Eva returned to the Cape with her children, where the V.O.C. gave them the old pottery workshop as a home.

She lapsed into such a dissolute and immoral life, however, that the V.O.C. again sent her to Robben Island on 26th March 1669, and placed the three children in the care of the free burgher, Jan Reyniersz. Eva returned to the mainland on various occasions, but was always banished to the island.

In May 1673 she was allowed to have a child baptized on the mainland and, in spite of her outrageous way of living, was buried in the church inside the Castle on the day after her death.

In 1677 the free burgher, Bartholomeus Borns recieved permission from the Council of Policy to take two of Eva’s children, Pieternella (Petronella) and Salamon van Meerhoff, with him to Mauritius. There Pieternella van Meerhoff married Daniel Zaayman (from Vlissingen), and, on 26th January 1709, arrived with her husband at the Cape, where she became an ancestor of the Zaayman family in South Africa. There were eight children born of this marriage, four sons and four daughters, of whom most (or all) were probably born on Mauritius.

The family has descended in the male line from the eldest son, Pieter Zaayman; two sons were baptized in Cape Town on 17 February 1709; two daughters were apparently married at the Cape (to Diodati and Bockelberg). A third daughter, Maria Zaayman, had already arrived at the Cape from Mauritius in 1708 with her husband, Hendrik Abraham de Vries, of Amsterdam (one of the four De Vries ancestors in South Africa) there being with her four children, of whom three boys were baptized simultaneously in Cape Town on 4 November 1708.

A fourth daughter, Eva Zaayman, date of birth unrecorded, was married (apparently at the Cape) first to Hubert Jansz van der Meyden, and later (20 September 1711) at Stellenbosch, to Johannes Smit of Delft. As far as is known no children resulted from these marriages.

Source: SESA (Standard Encyclopedia of Southern Africa)

Sir Donald Currie

June 4, 2009

Currie, Sir Donald

Sir Donald CURRIE was born in Greenock, Scotland on the 17th September 1825. He was the third son in a family of ten children born to James CURRIE (1797 – 1851), a barber, and Elizabeth MARTIN (1798 – 1839). He had four sisters and five brothers. Donald was an infant when his parents moved to Belfast. There he attended Belfast Royal Academy, the oldest school in Belfast and where one of the Houses was later named after him.At the age of 14, Donald started working at uncle’s sugar refining business – Hoyle, Martin & Co. in Greenock. This was not what he wanted and looking at his brother James, who worked as an engineer, he left and in 1844 joined the Cunard Steamship Company as a clerk. His career progressed so well that from 1849 to 1854 he established the company’s offices in Le Havre, Paris, Bremen and Antwerp. In 1854 he returned to its Liverpool head office. In 1862 he resigned and started his own North Sea shipping enterprise. He also founded the Castle Shipping Line which operated between Liverpool and Calcutta. By 1863 he had four new ships: the Stirling Castle, Roslin Castle, Warwick Castle and the Pembroke Castle. The next year two more ships joined the fleet: the Kenilworth Castle and the Arundel Castle. The Tantallon Castle joined the fleet in 1865 and was followed by the Carnarvon Castle (1867), Carisbrooke (1868) and the first steamship, the Dover Castle (1872).

In 1864 he made London the capital port for his ships. The London ship repair yards of the Castle Shipping Line, under the trading name of Donald Currie & Co., were founded on the banks of the River Lea. Later he switched from sail to steam and entered the Cape trade with sailings from Dartmouth, the first vessel to enter the service being the Icelandic which departed on the 23rd January 1872. His enterprise proved popular and soon the Union Steamship Company, which had enjoyed a monopoly, lost a large share of its traffic to the new line. He introduced fixed schedules, regardless of how little cargo was booked. Donald’s ships were in competition with the ships that had the Royal Mail run, as those ships were given precedence at ports. The first ship that Donald owned (instead of chartered) to do the Cape run was the Walmer Castle. It departed from Dartmouth and called at Bordeaux before arriving at the Cape in October 1872. In May 1873 the Windsor Castle reduced the passage time to the Cape to 23 days.

In 1876 the Cape mail contract was divided between the two lines and keen competition led to quicker voyages. Donald created the Castle Mail Packet Company with offices located at the Castle Shipping Line headquarters. Anderson & Murison were the Cape Town agents for Castle Mail Packet Co. with James MURISON being given Power of Attorney for all its business. He was assisted by Thomas Ekins FULLER, who later became Sir Thomas FULLER, High Commissioner for the Cape Colony, in London. Captain James lived in Sea Point for many years and was Cape Town ‘s most famous nautical man referred to as “the figurehead of Table Mountain, a prince among men” and “public-spirited, incorruptible and generous to a degree”. He first saw Table Bay in 1838, when he arrived from Scotland as mate aboard the Sir William Heathcote, a small brig that later traded along the coast, between Cape Town and Knysna. He later became a partner in the shipping firm of Anderson & Murison. He died at home in Sea Point in 1885.

Donald became quite involved in South African issues. On the 10th April 1875, President Thomas Francois BURGERS left Cape Town on the Walmer Castle on his way to England. The Transvaal Vierkleur was hoisted on that voyage when BURGERS celebrated his birthday. He met Donald at Plymouth and was hosted by him in London, where Donald assisted with the negotiations on the building of a railway to Delagoa Bay. In 1876 President Johannes (Jan) Hendrikus BRAND of the Orange Free State was also hosted by Donald. Donald helped to negotiate the diamond-fields compensation, receiving the C.M.G. and being thanked by the Orange Free State Volksraad. In 1877 and 1878 the Transvaal delegates of the first and second deputation which went to London to protest against the British annexation of the Transvaal turned to Donald for introductions to the Colonial Office. Stephanus Johannes Paulus KRUGER first met William Ewart GLADSTONE on one of Donald’s steamers during a Thames trip to Gravesend. Donald was also an active supporter of the return of the Transvaal to the Boers.

A model of the Dunvegan Castle was presented to President KRUGER by Sir Donald Currie. The model was first exhibited at the entrance of the State Museum of the South African Republic. It is now housed at Kruger House Museum in Pretoria.

The first news of the 1879 Battle of Isandlwana in the Zulu War was given to the London government through Donald’s shipping line. At that time there was no cable between England and South Africa. The news was sent by a Castle liner to St Vincent, and telegraphed from there to Donald. By diverting the outward mail ships, he helped the British government to telegraph faster instructions to St Vincent for conveyance by mail. This saving of time helped prevent the annihilation of the British garrison at Eshowe.

In 1881 Donald received the K.C.M.G. He was now a shipping magnate and a recognized authority on merchant shipping legislation, being responsible for important amendments to the Merchant Shipping Act of 1876.

He was a close friend of GLADSTONE. After an unsuccessful attempt at Greenock in 1878, in 1880 he entered Parliament as a Liberal member for Perthshire. In 1885 his political allegiance changed over the Irish question and, until his retirement from active politics in 1900, he was a Liberal Unionist supporting Joseph CHAMBERLAIN. He backed the British annexation of Damaraland, where he had business interests, forming a company to exploit the Otavi copper mine and St Lucia bay, which was annexed at the end of 1885.

As a Member of Parliament, he came up with the idea of converting fast merchant ships into armed merchant cruisers. This eventually led to the use of merchant ships in time of war. The Kinfauns Castle, built in 1879, was done so with this in mind.

In 1886-87, he made his first tour of South Africa. His business interests by then included diamonds and gold, and in 1888 he was one of the original directors of De Beers Consolidated Mines Ltd.

In 1891 the Dunottar Castle brought a British rugby team on a tour of South Africa. Sir Donald had given them a golden trophy to be used for internal competition. At the end of the tour the British team presented the cup to Griqualand West, the province they believed had produced the best performance of the tour. Sir Donald also donated a trophy for cricket competitions.

When the second Anglo-Boer War broke out, his fast steamers were in high demand. In 1900 the Dunottar Castle carried General BULLER and 1,500 British soldiers to the Anglo-Boer War. Sir Donald did not share the pro-Boer views of his son-in-law, Percy Alport MOLTENO (married to Elizabeth), on the causes of hostilities. Percy had joined his father-in-law’s business and on Sir Donald’s death in 1909, he inherited a large proportion of the estate.

It was Percy who started South Africa ‘s fruit exports to England, when in February 1892, the first 14 crates of peaches from the Stellenbosch district arrived at Covent Gardens. As manager Castle Mail Packets, Percy ensured that the ships had cold storage facilities. The first peaches, bearing the label “Cape Peaches”, were transported aboard the Drummond Castle which departed from Cape Town on the 13th January 1892.

When the Cape mail contract came up for renewal in late 1899, it was decided to award the contract to one shipping line. Instead of the Castle Shipping Line (1862 – 1900) and the Union Line (1792 – 1868) bidding for it on their own, Sir Donald proposed a merger of the two lines. On the 8th March 1900, the Union Castle Mail Steamship Company Ltd. was registered. The reception to celebrate the merger was held aboard the Dunottar Castle.

During a visit to Cape Town, Sir Donald saw the Cape Town Highlanders parading in full uniform. He was so impressed that he asked to meet the Officer Commanding. He acquired a Highland stag to lead the regiment. The stag, named Donald, was stabled at regiment’s headquarters in Buitenkant Street and looked after by a keeper, Private McDONALD. Sir Donald was made a life member of the regiment and on his departure a Guard of Honour was formed as he boarded the ship back to England.

In 1893 Sir Donald is recorded as having given a cheque to the Poor Jews Temporary Shelter in London. This was one of many cheques received from both the Castle and Union Lines. The Shelter served as a temporary residence for many Jews who made their way to South Africa as immigrants in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Sir Donald also made a donation in 1906 when the Shelter moved into a new building.

In 1893 the Union Steamship Company opened its own hotel in Cape Town, The Grand in Strand Street (demolished in 1973). Six years later, on the 6th March 1899, Sir Donald’s Castle Steamship Company opened a first class hotel on the Mount Nelson estate in Gardens. It was designed by English architects and managed at first by a Swiss, Emil CATHREIN. The Mount Nelson attracted an exclusive clientele. During the Anglo-Boer War it was the unofficial headquarters of the British Army and was often referred to as “Helots’ Rest”. Today it is more commonly known as Nellie or the Pink Lady, due to its famous” Mount Nelson ‘s Blush” paint which was first mixed for the hotel in the 1920s. The hotel has an interesting collection of memorabilia from the days of the Union Castle Line.

The present-day Centre for the Book is the finest Edwardian building in Cape Town. It was built just before WWI for the University of the Cape of Good Hope, on land donated by Willem HIDDINGH who also gave money, along with money from Sir Donald Currie. Both men are commemorated by bas-relief portrait busts in the entrance hall. The building was sod to the State in 1932 and became the Cape Archives Depot until they moved out in February 1990. The building was proclaimed a National Monument in 1990.

In 1908 his health began to fail. He died at Manor House, Sidmouth, Devon on the 13th April 1909 and was buried at Fortingall, Perthshire. A sculptured cross of granite, ten feet in height, marks his grave. A marble bust of Sir Donald is at Dunkeld Cathedral in Scotland. He paid for the cathedral’s restoration work in 1908, in gratitude to the minister’s daughter, who had nursed him through a serious illness.

He was married to Margaret MILLER, daughter of J. MILLER of Ardencraig. They had three daughters. A year after his death, his daughters donated £25,000 to the University of the Cape of Good Hope. A bronze plaque, with a relief profile, was placed in the entrance hall of the former building of the University to commemorate this gift.

Sir Donald acquired estates in Scotland and collected Turner paintings. Churches, universities and the city of Belfast benefited from his generous spirit. In 1880 he was awarded the Fothergill gold medal by the Royal Society of Arts. He received the G.C.M.G. in 1897. In 1906 the University of Edinburgh conferred an honorary LL.D. degree on him, and he was granted the freedom of the city of Belfast. He endowed at his old school, Belfast Royal Academy, the school’s most prestigious scholarship known as the Sir Donald Currie Scholarship.

For many years, it was Sir Donald’s ships that brought mail, cargo, immigrants and visitors to South Africa. Many South Africans have fond memories of sailing on his ships or watching them while in port. Shipping advertisements in England and South Africa stated that they provided cheap steerage and third class passenger fares. The other shipping companies that specialised in passengers and cargo to Cape Town or dropped off passengers in Cape Town while their ships were en route to New Zealand or Australia could not offer cheaper rates. Between 1891 and 1900 the Union Line had 12 new ships, each capable of carrying about 800 third class passengers and about 400 in steerage. The Castle Line, at the same time, had 24 new ships, many of them capable of carrying between 100 and 150 third class passengers with several hundred in steerage. In the late 1880s the Board of Trade reported that there were over 16,000 passengers travelling to African ports.

The “Year Book and Guide to Southern Africa” was compiled by the Union-Castle Mail Steamship Company from 1893 to 1967. In 1950 it was split into two volumes, one being the “Year Book and Guide to East Africa”. The books were published by Robert Hale Ltd., London, and edited by A. Gordon-Brown.

The Union Castle ships sailed between England and South Africa until 1977. On the 24th October 1977 the last mail ship, with passengers, left Cape Town for Southampton. The Southampton Castle was given the honour of doing the last run. Capetonians were used to seeing the mail ships, affectionately known as Lavender Ladies (for its lavender hulls), arriving in port, mostly on a Wednesday from England. There used to be an “Ocean Post Office” in Cape Town with its own postmark. Other postmarks that related to these mail ships included “Posted at Sea” and “Too late – ship sailed”.

References:

Dictionary of South African Biography

The British Pro-Boers: 1877-1902, by Arthur Davey, Tafelberg 1978

Mail ships of the Union Castle Line, by C.J. Harris and Brian D. Ingpen, Fernwood Press, 1994

Under Lions Head: Early days at Green Point and Sea Point, by Marischal Murray, A.A. Balkema 1964

The Journal of Lt.-Col. John Scott (Cape Town Highlanders), published in the SA Military History Journal, Vol 1 No 5

Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_Currie

Kruger House Museum : http://www.nfi.org.za/KM/khindex.htm

Article researched and written by Anne Lehmkuhl, June 2007

Bowler, Thomas William

June 3, 2009Born in Tring, Hertfordshire, England, 9.12.1812 – Died London, England, 24.10.1869

Thomas William Bowler, an artist, and the son of William Bowler and his wife Sarah Butterfield. Both parents were of humble origin and probably Nonconformists believing in adult baptism.

Bowlers’ grandmother was housekeeper to Dr John Lee, F.R.S., a keen amateur astronomer and owner of Hartwell House, Hartwell, Buckinghamshire. In about 1833, through the good offices of Lee, Bowler, who had spent three years as a lawyer’s clerk in London, met the Maclear family, then living near Hartwell. Consequently, when Thomas Maclear arrived at the Royal Observatory, Cape Town, as astronomer royal on 5.1.1834, he was accompanied by Bowler as his manservant. Bowler embellished some of Mrs Maclear’s letters to England with marginal drawings of scenes round and about the observatory building. In later years he put this idea to commercial use when a series of drawings by him was steel-engraved on note-paper and published by A. S. Robertson in the Heerengracht (Adderley Street). One of Bowler’s drawings on a Maclear letter dated 10.5.1834 is signed by him and is probably his first signed drawing in South Africa: a view from the large wing-room at the observatory.

In August 1834 Maclear had found Bowler an official post at the observatory at a salary of seventy pounds per annum. In addition to acting as general factotum, cleaning the lamps and instruments, and carrying messages to and from Cape Town, Bowler began to learn the rudiments of astronomy, in which he maintained an interest for the rest of his life. By early 1835 he was making corresponding observations at the transit instruments with Maclear, and had been invited by Sir John Herschel to observe the moon through his reflector at Feldhausen, Claremont.

Nevertheless his personal relations with Maclear, which had never been cordial, led to Bowlers’ dismissal on 8.7.1835. He immediately took up employment as tutor to the children of Capt. R. T. Wolfe, commandant of Robben Island, at a salary of forty pounds a year and free board. In 1838 he married Jane Elizabeth Hawthorne, a young Irish girl, and towards the end of the same year left Robben Island, finding employment in Cape Town with Wolfe’s assistance. In the Cape of Good Hope directory for 1839 his name appears for the first time among the inhabitants of Cape Town. He had then set up as a ‘professor of drawing and landscape painter’ at 31 Boom Street. This was the period of Bowlers’ early development as an artist, and there are extant a few examples of his first inadequate attempts to record his surroundings, particularly views from, and of, the observatory.

By April 1841 he was able to inform Lee of his remarkable progress after five years of studying art, during which period he had set himself up as a drawing-master and landscape painter. For the next thirty years he was to be a recorder of events and scenes at the Cape and in Natal, in which the march of history was accurately preserved for posterity. The earliest of the Bowler prints dates from 1842, when the lithograph of H.M.S. Southampton covering the landing of the 27th Regiment off Port Natal was published. It is doubtful whether Bowler visited Natal in 1842; he was, however, there in August 1845 and in October of that year advertised the publication by subscription of five views of Natal, to be dedicated to the Cape Governor, Lieutenant-General Sir Peregrine Maitland.

In 1843 he moved to 65 Longmarket Street. By 1844, when he was making a fair income by teaching art to the children of many of the town’s leading citizens, Bowler conceived the idea of publishing an annual series of pictures of scenes and views of the Cape. The first of the series, which arrived in Cape Town in November 1844, was Four views of Cape Town, comprising ‘Table Bay’; ‘Cape Town on the beach near the military hospital; ‘Cape Town near the Amsterdam Battery; and ‘Cape Town from Tamboers Kloof, Lion’s Hill’. His original intention of annual publications, however, never materialized.

The print of Simonstown was issued in 1845 when Bowler was living in the Buitekant. One of his pupils at this time was Sir John Wylde, Chief Justice of the Cape. By this time Bowler was earning well-merited praise as an artist, and was a man of substance, but five years were to elapse before his painting entitled ‘Great meeting held in front of the Commercial Hall, Cape Town, on 4th July 1849′ (now in the Cape Archives, Cape Town) was to appear, at the time of the anti-convict agitation at the Cape.

In that year Bowler’s wife died, aged forty-one, leaving four sons and two daughters. Her tombstone is preserved in the Cultural History Museum, Cape Town. The family now moved to 23 Burg Street, for a short time only, for in 1850 Bowler’s address was Garden Overbeil, at the upper end of Keerom Street. On 26.2.1851 he married Maria Jolly, one of the four talented sisters who ran a girls’ school, which became the Good Hope Seminary in 1873. She bore him four daughters, two of whom died young. One son of his first marriage died from exposure after a shipwreck in December 1863 and another by drowning in July 1869.

In 1852 Bowler and his family were living at Wynberg, where their home was a meeting-place for art and music-lovers. In addition to his private drawing-classes, Bowler was teaching at the South African College, Cape Town (where he started on 5.4.1842) and the Diocesan College, Rondebosch, at the same time maintaining his output of meticulously detailed paintings, exhibiting a number of them at the first fine arts exhibition held in Cape Town in February 1851, and gaining a gold medal for one of them. At the same time he disposed of about fifteen paintings through a type of lottery known as an ‘art union’, probably the first ever held at the Cape. Over the years he continued sporadically to dispose of his pictures in this way; the Art Unions Bill of 1860, which legalized this form of lottery, was introduced and passed in the Cape Parliament on his recommendation.

In about May 1854 Bowler went to England, probably mainly for health reasons. During his stay he took lessons with J. D. Harding, the great English water-colourist and lithographer, and on his return introduced the Harding system of drawing instruction to his pupils at the South African College. In January 1855, after his daughter had died, Bowler moved from Wynberg to 3 Burg Street, Cape Town, where he began teaching adult classes by the Harding method. Within a month he was living at 22 Grave Street (now Parliament Street), which was to be his home for a few years. One of his favourite pupils was Maria de Wet, afterwards Maria Koopmans-de Wet. In the first volume of the Cape Monthly Magazine (May 1857) Bowler contributed an article, ‘Art at the Cape’, which sheds light on his views of art teaching and gives an appreciation of the Cape from the artist’s point of view. He discourses on the uselessness of teaching art by making pupils copy the works of others, and advocates the cultivation of the powers of vision through observation and reflection. In 1858 he was a voluntary teacher at the Mechanics’ Institute, but it was not until April 1861 that he opened his own art school, one of the first in Cape Town. In June 1859 he was baptized in St George’s Church, Wale Street, where for years he was a regular worshipper.

Bowler’s tremendous output was in no wise reduced by his teaching obligations. In March 1855 his lithographic album, South African sketches, was offered for sale; towards the end of the same year he published the African sketchbook. A third album, A pictorial album of the colony of the Cape of Good Hope, which he began preparing in 1854, was published in September 1865.

Meanwhile Bowler continued to travel extensively in the Cape Colony. In mid-1857 he visited Knysna and George, executing commissions for local residents; his views of the Mosenthal Company’s branches were probably done at this time. In the early part of 1858 Bowler visited the eastern districts and Kaffraria, repeating this journey in December 1861 – January 1862, when he sketched the views forming the basis for his celebrated series, The Kafir wars and the British settlers in South Africa, the text being by W. Rodger Thomson, who also wrote the text for his Pictorial album . In 1859 he visited the Swellendam district, where he painted several scenes for the Barry family; and en route he recorded the scene at the first agricultural show at Caledon.

His reputation had spread to England in 1860, when two of his water-colours were hung in the Royal Academy. Several of his sketches, such as those depicting the opening and completion of the Cape Town-Wellington railway (1859-63), and Prince Alfred’s visit to the Colony (1860) were used by the Illustrated London News. When the prince (then Duke of Edinburgh) visited Cape Town again in 1867, Bowler recorded the event in a print for which he himself was the lithographer. In 1862 he moved to Wale Street, which was his last home.

In December 1865 Bowler journeyed to Mauritius, returning home two months later with a thick sketch-book recording his experiences. As he failed to find sufficient subscribers for an album, the pictures were never published.

At this time an opposition art school was opened and Bowler had to struggle to make a living. This, together with an unsuccessful lawsuit at the end of 1867, which had confronted him with financial difficulties, made him return to England. He left on 28 August 1868, first revisiting Mauritius, where he contracted a fever (probably malaria), and then proceeded to Egypt. He died of bronchitis in the Middlesex Hospital, London, after a ten-day illness.

Bowler was frequently disliked for his quick temper and aggressiveness, which manifested themselves in numerous public quarrels; his renown, however, rests on his ability as an artist and art teacher. As a teacher his method was based on Harding’s principle of learning ‘to draw from nature’. Bowler ‘s The student’s handbook – intended for those studying art in the system of J. D. Harding (Cape Town, 1857) was indeed a condensation of Harding’s Lessons on trees and elementary art. Bowler numbered among his pupils some of the Cape’s most competent artists such as Abraham de Smidt and Daniël Krynauw, though he founded no typically indigenous school of art.

As an artist Bowler was probably, with the exception of W. D. de Vignon van Alphen, the only painter of real merit in South Africa during the mid-nineteenth century. A descendant of the picturesque school of topographical artists, which was to reach its apogee in the work of English water-colourists such as Turner, Cotman and De Wint, Bowler, like his English counterparts, had as much of the landscape painter as the topographer in him. Though much of his work is a statement of the cliches into which the water-colour school was to fall, his taste was always impeccable. The sketch-books in the Mendelssohn Collection of the library of Parliament, Cape Town, which were intended only for his own eyes, show in addition that he was capable of a high degree of freshness and originality when he escaped the pot-boilers from which he earned a living. It is in his seascapes, too, that his ability as an artist is most apparent, for he loved and knew the sea in all its moods. Bowler ‘s chief merit lies, however, in his role as a pictorial historian of Cape society in the pre-photographic era, as a recorder of every important local event, from the laying of the first stone of the Table Bay breakwater to the arrival of the Confederate raider Alabama , and, above all, as one who strove unfailingly to make the people of the Cape art-conscious.

By 1967, the year of the publication of Bradlow’s definitive biography, 538 of Bowler ‘s originals (excluding the albums in the Mendelssohn collection) had been traced. Of these nine are oils, 413 water-colours and 106 pencil sketches. Bowler is, however, best known to the public for the so-called Bowler prints. There were sixty-six published prints, of which sixty-four were re-produced by the lithographic process, and two as steel engravings. Of the sixty-four lithographs, fifty appeared in four albums: South African sketches; The African sketchbook; The Kafir wars and British settlers in South Africa and Pictorial album of Cape Town. Of the remainder, ten appeared at different times and four ( The four views of Cape Town ) were published in a separate folder. The term ‘original print’, when applied to Bowler’s prints, signifies those prints which were produced in Bowler’s own time.

There are in the Fehr Collection, Cape Town, a miniature (c. 1834) showing Bowler as a fresh-faced young man with beautiful hands, and a portrait by J. A. Vintner painted in 1854. The carte-de-visite photograph of Bowler by Lawrence Bros. is in the portrait collection of the S.A. Library, Cape Town. Dated 1863, it forms the frontispiece of Bradlow’s work. There are other photographs in the Cape Archives. E. BOWLER

(Source: Dictionary of South African Biography, Volume II)

Bowler, Thomas William

The History of Photography at the Cape

May 29, 2009Cc

The camera obscura, an apparatus for tracing images on paper, was in common use by the 18th century as an aid to sketching. The earliest attempts to fix the images by chemical means were made in France by the Niépce brothers in I793, and in England by Thomas Wedgwood, an amateur scientist, at about the same time. Early in the 19th century further progress toward the invention of photography was being made simultaneously in France, England, Germany and Switzerland.

Of significance to photography in South Africa are the achievements of the English astronomer and scientist Sir John Herschel, who resided at the Cape from 1834 to 1838. It is thought that his experiments in connection with the development of photography advanced considerably while he lived at Feldhausen in Claremont, near Cape Town. In March 1839, only a year after his return to England, he revealed to the Royal Society the method of taking photographic pictures on paper sensitised with carbonate of silver and fixed with hyposulphite of soda. These discoveries had been accomplished independently of W. H. Fox Talbot, whose paper negative process (calotype, later called talbotype) became the basis of modern photography, and Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, whose process (daguerreotype) resulted in a positive photographic image being produced by mercury vapour on a silvered copper plate.

It is generally acknowledged that Herschel was the first to apply the terms ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ to photographic images and to use the word ‘photography’. He was also the first to imprint photographic images on glass prepared by coating with a sensitised film. Daguerre’s invention, announced in Paris in 1839, was slow in reaching the Cape; and although apparatus was advertised for sale in 1843, there is no evidence of photographs taken before 1845. The earliest extant photograph in South Africa was taken in 1845 by a Frenchman, E. Thiesson, who had photographed Daguerre himself the year before. The first portrait studio was opened in Port Elizabeth in Oct. 1846 when Jules Leger, a French daguerreotypist, arrived there from Mauritius. He took ‘photographic likenesses (a minute’s attendance)’ in a private apartment in Ring’s library, proceeding within a month to Uitenhage and Grahamstown. Leger left the country the following year, but not before his former pupil and assistant, William Ring, had succeeded him in the new art.

In Cape Town the first professional daguerreotype portraits were taken outdoors in December 1846 by the architect Carel Sparmann, at ‘all hours of the day and according to the latest improvements made in the art by himself’. He advised ladies to wear dark dresses in silk or satin, or Scotch plaid, the plaid being a pattern which showed itself with great exactness. Concerning gentlemen, the less there was of white in their clothing the greater the effect.

Daguerreotypes, usually about 5 x 8 cm in size, were bound up with a gilt mat and cover-glass to protect their fragile surfaces before being placed in velvet-lined case. The image was clearly defined, but the silver plate was costly and early Cape daguerreotypists often went bankrupt. Nevertheless they persevered in their portraiture and, to a much lesser extent, in taking views of buildings and street scenes, which were not generally for public sale until the 1800′s. Landscapes, pictorial subjects, and the early ‘news’ types of photography were at first more often the province of enthusiastic amateurs. The artisan-missionary James Cameron was experimenting with the calotype process for outdoor work before 1848, the paper negative being characterised by broad effects of light and shade. His photographs of the Anti-Convict Agitation meetings (1849) in Cape Town are the earliest known outdoor events in the Cape recorded by the camera and served as a basis for engravings made by the artist-photographer William Syme. Other early amateurs were William Groom, whose hand-coloured photograph of Wale Street, Cape Town (1852) is the earliest outdoor photograph extant in South Africa; Michael Crowly, who recorded the large number of wrecks in Table Bay (1857); and William Millard, who took the first panoramic view of Cape Town from Signal Hill (1859).

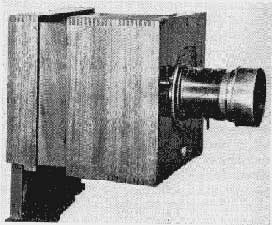

"oldest camera" in South Africa, brought to the Cape by Otto Mehliss of the German Legion (Photographic Museum, Johannesburg)

Scott Archer’s collodion process, introduced in the Cape in 1854, enabled prints to be made on sensitised paper from a collodion glass negative, resulting in a clearer rendering of half-tones. In field work the technique was particularly cumbersome as the plates had to be prepared on the spot and processed while still wet, necessitating the use of a portable dark-room such as a wagon, cart or tent. For all that, photography flourished during the collodion period, which lasted in the Cape until 1880 when James Bruton introduced the dry plate. Collodion portraits on glass (glass positives or ambrotypes) are sometimes confused with daguerreotypes, as they were made in the same sizes and fitted into similar cases. While the image of the glass positive is dull in appearance and can be seen at any angle, the daguerreotype has a shimmering, mirror-like reflecting surface which prevents the image being seen from every angle. For dating purposes professional daguerreotypy was practised in the Cape from 1846 to 1860, and glass positives were taken from 1854 until well into the 1870′s, although they were less in demand after the introduction of the carte-de-visite, a type of photograph, in 1861.

The art potential of photography was brought to public attention in 1888 at the third Fine Arts Exhibition in Cape Town. In addition to local contributions from professional and amateur photographers, there were importations from abroad. The first important use of photography for documentary purposes was achieved by William Syme and Frederick York when they published their portfolios of photographs of works of art displayed at this exhibition. No copy of either publication has as yet been traced. Earlier in the year the first general display of photographs had been held at the Grahamstown Fine Arts Exhibition, one of the organisers being the amateur photographer Dr. W. G. Atherstone, who had been present in Paris when Daguerre’s process was made public on 18 August 1839.

At the Paris Universal Exhibition in 1867 he exhibited photographs of Eastern Cape scenery, together with photographs illustrative of South African sport and travel by the explorer James Chapman, a pioneer well known for his impressive photographs of the Zambezi Expedition, which were on view at the South African Museum in 1862. An account of this expedition is given in Thomas Baines’s diary. He recounts how the photographer’s efforts were hampered in countless ways.

In the Eastern Province the majority of photographers had no fixed establishments, moving from town to town and serving a small population. Not many were as enterprising as the general dealer Henry Selby, who opened a studio in Port Elizabeth in 1854 and a branch at Uitenhage in 1855. Practising the daguerreotype, collodion and talbotype processes, he introduced stereoscopic portraits and vitrotypes (a process of producing burnt-in photographs on glass or ceramic ware), sold photographic materials and was also the first to sell views of Port Elizabeth (1856). With his partner James Hall he erected the first glass-house in the Eastern Cape (1857). This was a small wooden building with a roof consisting mainly of glass skylights and a number of panes of glass in its walls. Providing sufficient light for indoor portraiture and easily dismantled, it was especially useful to itinerant photographers. A drawback was the harsh glare of light, which irritated sitters, but more pleasing pictures were obtained by several Grahamstown photographers when they erected blue glass-houses in 1858. Arthur Green draped his with curtains.