You are browsing the archive for Second Anglo-Boer War.

Sarah Gertrude Millin

July 6, 2011

Sarah Gertrude Millin was born in Zagar, Lithuania circa March 1888 and died in Johannesburg on the 6th July 1968, authoress, was the eldest child and only daughter of Isaiah Liebson, a Jewish merchant, and his wife, Olga Friedmann. According to Sarah M. her birth was not registered: calculations indicate that she must have been born about March 1888. Her maternal grandfather had been a Kimberley pioneer and while visiting Europe persuaded Isaiah and Olga to join the Litvak immigration to South Africa during the 1880s.

The Liebsons, with their five-month-old daughter, arrived in Cape Town in August 1888 and went on to Beaconsfield, near the Kimberley diamond-fields, where Isaiah opened a trading store. In 1894 the family settled at Waldeck’s Plant, a section of the Vaal River alluvial diggings in the Barkly West district. Sarah M.’s father, never a good businessman, managed to make a fairly comfortable living among the European diggers, Black labourers, and Coloureds by exercising trading, water, and ferry rights and by running a small cattle farm that showed no profit.

Sarah Millin and her six brothers (one died at the age of three) appear to have been the only White children at Waldeck’s Plant, a circumstance of decisive influence on her later views regarding South Africa’s multi-racial society. She began to write poetry when she was six, taught herself German with her mother’s encouragement and the aid of a school primer, and developed the voracious reading habit that was to damage her eyesight permanently. She first attended school at Beaconsfield, staying with relatives there, then continued in Kimberley, living in boarding houses until the outbreak of the Second Anglo-Boer War in 1899. From this period dates her life-long insomnia, the outcome of unfamiliar bedrooms, absence from her family, and fear of the dark.

At the end of the war Sarah. became a pupil at the Kimberley High School for Girls, where she achieved a first-class Matriculation pass in 1904. Her marks were the highest for girls in the Cape Colony and brought her a special citation for distinction in mathematics. She also won the Victoria Memorial Exhibition, the University Bursary, and was awarded a Barnato Scholarship. Eyestrain and physical debilitation prevented her from pursuing a university education at the South African College, Cape Town. Instead, she studied music in Kimberley, receiving her teaching certificate in 1906. But she never taught, preferring to devote her talents to literature.

When she was eighteen Sarah M. had a short story, ‘A feeder on husks’, printed in the Johannesburg Sunday Times; several of her essays, sketches, and articles appeared in the Zionist Record and The State during 1910-12. While visiting Cape Town she met and became engaged to Philip Millin, a local part-time journalist studying for the Bar. After their marriage in Kimberley on 1.12.1912 they moved to Johannesburg where Sarah M. did book reviewing for the Rand Daily Mail, wrote an occasional column under the pseudonym of ‘The Johannesburg Girl’, and had four short stories published in Truth (October-November 1915). Miscegenation is a recurring theme in Sarah M.’s fiction; it provided the motif for her first novel The dark river (1919), which drew upon childhood experiences of the diggings at Waldeck’s Plant. Middle class (1921) and Adam’s rest (1922), the latter book also dealing with the Coloured problem on the diggings, increased her overseas readership – but, as with her first novel, neither of these works aroused much interest in South African literary circles. Meanwhile she had been corresponding with the New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield, then living in England, who during 1921 arranged for the publication of several of Sarah M.’s short stories in the London Athenaeum and Adelphi. These tales were subsequently included in Sarah M.’s collection Two bucks without hair (1957). Other short stories from her pen were collected in a volume called Men on a voyage (1930). The Rand miners’ strike of 1922 saw Sarah M.’s husband and one of her brothers join the volunteer militia; she witnessed the shelling of Fordsburg from her house on Parktown ridge. The literary outcome of her experiences was The Jordans (1923), a novel strongly anti-socialistic that she dedicated to General J.C. Smuts*. Sarah M. then wrote God’s stepchildren (1924), the book that established her literary reputation overseas and brought financial success. Although her abhorrence of miscegenation at times overshadowed her sympathies for the Coloured outcast, she achieved in this novel a realism previously absent from South African fiction dealing with racial questions.

During 1924-6 she and her husband travelled to Europe on two occasions. In England Sarah M. met various celebrities, among whom were D.H. Lawrence, G.B. Shaw, Storm Jameson, Rebecca West, and the now deceased Katherine Mansfield’s husband Middleton Murray. These encounters, though brief, confirmed her standing with the overseas literary establishment and were some consolation for the continuing neglect of her in South Africa. Mary Glenn (1925), a novel dealing with the psychology of mother-child relationships, was favourably received by English and American critics; subsequently, encouraged by John Galsworthy, Sarah M. adapted this book for the stage and it was produced as ‘No longer mourn’ at the Gate Theatre, London, in November 1935.

With The South Africans (1926), a sensitive and stylistically elegant account of the peoples, history, and customs of the sub-continent, Sarah M. found her local public. Enlarged to include her assessment of the spread of pre-World War II (1939-45) Nazi ideals among certain sections of the community, and re-entitled The people of South Africa (1951), this popular book takes its place among Sarah M.’s non-fiction with two other important works: the biographies Rhodes (1933) and General Smuts (1936).

Sarah M. was able to consult Sir Patrick Duncan* and General Smuts about the accuracy of events described in Rhodes before its publication; her treatment of the subject was notably impartial and perceptive and the biography became a Book Society choice in England. While visiting that country in 1933 Sarah M. sold the film rights to Gaumont British Films, for whom she wrote a scenario. Much to her chagrin, a romanticised version of her work entitled ‘Rhodes of Africa’ was screened in 1936.

While working on General Smuts she had access to hitherto unavailable family papers and to government documents and letters covering the period from Smuts’s early life to the years after the First World War (1914-18). In the course of accumulating factual information, she stayed for some time with Smuts and his family at Doornkloof, their home outside Pretoria. The resultant two-volume work was of historical importance for future researchers yet patently flattering of a statesman, if not a politician, for whom M. had the greatest admiration.

Not surprisingly, several of her novels touch on the problem of artistic frustration. An artist in the family (1927) and The fiddler (1929), the film rights of which Sarah M. sold to an American company, exemplify this aspect of self-projection in her characters. Another novel, The coming of the Lord (1928), is typical of her concern for minority groups since it records the Bulhoek massacre of 1921 in the Cape Colony where members of the Black Israelite sect were killed by government forces when resisting forced removal.

After Galsworthy had persuaded her to start a branch of the PEN Club in South Africa, Sarah M. attended the Oslo international congress of this organization in June 1928, as a representative of her country. She resigned from the Club in 1960 after being accused of supporting apartheid. In September 1929 she agreed to undertake a lecture tour of America. Although ill health forced the cancellation of lecturing engagements, she spent two months in the States treated as a literary celebrity and meeting F.D. and Eleanor Roosevelt, President Hoover, and, of more importance to her, the writer Theodore Dreiser. Her novel The sons of Mrs Aab (1931), a well-written domestic tragedy, was dedicated to Dreiser.

Seeking clearance for the use of British government papers in her General Smuts, Sarah M. went to London in 1936. While there she agreed to accompany Lady Muriel Paget, a relief worker among displaced British subjects, on a visit to Russia. After leaving her companion at Leningrad, she went on to Moscow alone to be introduced to the Soviet Commissar for Foreign Affairs as well as the Lithuanian Prime Minister. Back in London, she discussed the fate of European Jewry with Stanley Baldwin, Anthony Eden, Winston Churchill, Austin Chamberlain and other politicians. She was committed to the cause of Zionism, having accommodated Chaim Weizmann and his wife on their fund-raising trip to South Africa in 1932 and, in turn, stayed with them when visiting Palestine in 1933. On the first anniversary of Israel’s independence in 1949, she attended the celebrations as Smuts’s personal emissary to Ben-Gurion, the Prime Minister.

Politics and the imminent outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 occupied the major share of her attention after returning from England in 1938. Frustrated by what she saw as Smuts’s expediency and procrastination at a time of internal crisis, she turned to J.H. Hofmeyr* as the saviour of South Africa. Her incessant counselling of Hofmeyr by an extensive correspondence was politically fruitless yet significant in the context of her shifting preoccupations, What hath a man? (1938) and The Herr Witchdoctor (1941), because of their strong anti-German propaganda, were basically flawed novels.

Sarah M. wrote The night is long, the first part of her autobiography, in 1939; then, at Smuts’s suggestion, she began her War diary. This work, an incidental record rather than the envisaged historical account of the Second World War, was of current interest yet had poor sales; six volumes were published: World blackout (1944); The reeling earth (1945); The pit of the abyss (1946); The sound of the trumpet (1947); Fire out of heaven (1947); The seven thunders (1948). In 1943 she sent Smuts the manuscript of ‘The glass house’, an allegory about the punishment of German war criminals. He advised, and she reluctantly agreed, that this work should not be published.

Sarah M.’s husband Philip, who had become prominent in legal circles since his appointment in 1937 as a judge of the supreme court, accompanied her on a visit to America, Canada, and Britain in 1946; at the invitation of the American prosecutors they were able to attend the Nuremberg war trials. On returning to South Africa Sarah M. resumed the writing of fiction without, however, regaining her former excellence. King of the bastards (1949), with Coenraad de Buys* as the principal character, was an exception and proved something of a local best-seller. The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, awarded her an honorary doctorate of literature in March 1952; a month later Philip Millin collapsed and died of a heart attack in the Johannesburg law courts. Sarah M. was inconsolable. She adored her husband, who had been of inestimable value to her as a critic of her writing. The measure of my days (1955), the concluding section of her autobiography, paid tribute to him. With much of her energy and inspiration gone, she withdrew from the social life she had shared with her husband for forty years and occupied herself with sporadic bursts of writing of a sociopolitical nature. Among these were White Africans are also people (1966), which she compiled and to which he contributed. It contains a collection of articles presenting the case for the survival of the European. From 1962 onwards she corresponded regularly with Sir Roy Welensky, Prime Minister of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland; after Rhodesia’s unilateral declaration of independence in 1965 she sent R1 000 every two months to Rhodesia in support of the Smith government.

Sarah M.’s last published novel was Goodbye, dear England (1965), an historical narrative of the two world wars, to which she wrote a sequel first called ‘Goodbye, dear world’ and later changed to ‘Time no longer’. She was not able to find a publisher for the sequel or for her history of the Jews, ‘A certain people’. Embittered and lonely, she died childless at eighty of a massive thrombosis, and was buried beside her husband in Westpark Jewish Cemetery. She left an estate valued at R550 000.

With an abrasive personality and domineering attitude, Sarah M. made enemies easily. Yet she could be most generous to those who gained her sympathy – especially to young, struggling authors. Her growing acceptance, in principle, of separate development for the Black and the White races in Africa alienated her from the liberal Left and resulted in many adverse estimations of her work. In her historical writings she was largely impressionistic and lacked the necessary measure of scholarly objectivity; as a novelist she was the foremost writer of her generation. Her realistic portrayal of regional character and scene, notable for lucidity and precision of expression, remains of germinal importance to the development of South African English fiction. Photographs of her are to be found in Rubin (infra).

Barend Jacobus Vorster

April 17, 2011Barend Jacobus Vorster (the younger) born on 26th May 1858 at Kalkbank, Pietersburg district and died on the 17 April 1933 a politician and farmer, was a son of Comdt B. J. Vorster, of Soutpansberg. To distinguish him from his father he was usually called ‘Klein Barend’ (‘Little Barend’) or, as he limped, ‘Kreupel Barend’ (‘Cripple Barend’). As a young man he, about 1875, helped the Rev. Stephanus Hofmeyr with mission work in Soutpansberg, and considered becoming a missionary.

Vorster was influential in his area, and in 1890 took part in the organization of the Adendorff trek across the Limpopo to Banyailand. He was the chairman of the committee appointed to organize the trek in the Soutpansberg district, and a member of the expedition that reached a land agreement with a number of Banyai chiefs. In the following year attempts to trek were prohibited by the Transvaal republic for diplomatic reasons, and Vorster lost support, partly because he was accused of negotiations with Cecil Rhodes. He thus withdrew from the expedition.

In 1889 he represented Soutpansberg in the volksraad. When the Tweede (‘Second’) Volksraad was established he became a member in 1891, and from 1897 a member of the Eerste (‘First’) Volksraad.

At the outbreak of the Second Anglo-Boer War the government made V. its native commissioner at Spelonken, north-east of Pietersburg, where he was also confidential adviser to Gen. F. A. Grobler. When Grobler left the northern area V. was appointed chief commandant of Soutpansberg. As an official he was considered ambitious and haughty.

In the Pietersburg district he farmed at Doornkasteel and then at Zaaiplaats. He married twice, first Johanna Wilhelmina Christina Mulder and then a widow, Johanna Petronella Smit. He was survived by four sons and three daughters. There are portraits in the album collection of the National Museum of Cultural History, Pretoria, and in Lig in Soutpansberg.

Wilhelm Wolfram

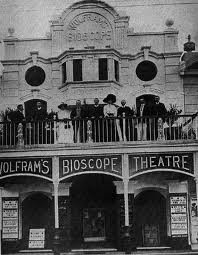

April 16, 2011Wilhelm Wolfram was born in Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, Germany on the 3rd July 1860 and died in Cape Town after 1920). He was a pioneering cinema showman and was educated in Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. He came to South Africa in 1895 and was employed in Johannesburg as an engineer on the Ferreira mine and others. In October 1899, on the outbreak of the Second Anglo-Boer War, he toured the country with motion pictures and had, according to S.A.W.W., 1916, special permits to produce war scenes.

He enjoyed the laughter of children and specialised in comic films as well as long nature study documentaries. His popularity was unrivalled and by 1909 he had begun to concentrate on Cape Town, where he was assured of large, regular audiences. On 16.4.1910 he opened a permanent cinema known as Wolfram’s Bioscope at the bottom of Adderley Street. It seated 565 people. He personally operated it for many years, resisting incorporation into commercial circuits, but finally ceded it to I. W. Schlesinger’s African Consolidated Theatres, the building being demolished in the early thirties.

The popularity of Wolfram’s bioscope has left its mark uniquely on the official languages of South Africa. The terms ‘cinematograph’, ‘cinema’ and ‘kinema’, for an exhibition of moving pictures could not displace in popular speech the already strongly-entrenched ‘bioscope’ that W. introduced.

An upright, honourable man, Wilhelm died in obscurity. There is a portrait of him in S.A.W.W.

Adriaan Jacobus Louw Hofmeyr

April 13, 2011Born in Calvinia on the 13 April 1854 and died in Bellville, Cape Province on 01 May 1937, minister of the N.G. Kerk and political agitator, was the eldest son of Prof. N. J. Hofmeyr of the Theological Seminary, Stellenbosch, and his wife, Maria Magdalena Louw.

Hofmeyr was educated at Stellenbosch where he completed the B.A. degree at the Victoria College and his training at the Theological Seminary. In 1879 he was admitted to the ministry and in 1881 ordained at Willowmore. In 1883 he was called to Prince Albert, and was, as in the previous parish, active in promoting church music and rehabilitating the indigent. Requested by the Cape Church, he visited its members in Mashonaland in 1891, becoming an enthusiastic supporter of Cecil John Rhodes’s plans for expansion north of the Limpopo. Although he made his mark as a public speaker he refused a request to stand for election to the Cape parliament. After the Jameson Raid (1895-6) he tried in vain to reconcile J. H. Hofmeyr (Onze Jan) and Rhodes.

In 1895 he accepted a call to Wynberg but in July 1899 the Presbytery found him guilty of serious misconduct and suspended him.

Subsequently he settled in Bechuanaland where he was mainly active with political propaganda against the government and the policy of the neighbouring Transvaal Republic. He acquired an unfavourable reputation among the Afrikaners as being markedly pro-British and shortly after the start of the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) he was taken prisoner by an invading Boer commando at the Palapye railway station. From November 1899 he was detained in the State Model School in Pretoria together with British officers who were taken prisoner and with whom he identified himself completely. Among them was the British journalist Winston Churchill. When Pretoria was occupied in June 1900 he regained his freedom and on the recommendation of Sir Alfred Milner, whom he taught Afrikaans, was engaged as agent by the military authorities to persuade the republicans to lay down their arms. His efforts failed, however, and after several months he left for England where he published an account of his experiences during captivity under the title The story of my captivity (London 1901). The work was characterised by declarations of loyalty towards Britain and contempt for the fighting Boers.

Next he campaigned to influence British public opinion against the deputation of the Cape politicians, John X. Merriman and J. W. Sauer, who visited England from January to July 1901. By means of letters in the London press he also tried to refute the disclosures of Emily Hobhouse about the concentration camps. The issue was confused, however, when the Liberal opposition press released the facts connected with his suspension from the ministry and stressed that H. had no status or prestige among his own people.

After the war he settled at Kuruman. In 1926 he was readmitted to the ministry and became assistant minister at Heilbron.

In 1928 he was ordained minister at Kuruman and retired in 1933. He married Anna Joubert. A photograph of him appears in The story of my captivity (supra) and in the Jaarboek van die Nederduits Gereformeerde Kerke in Suid-Afrika, 1938.

Boer Prisoners of War in Bermuda

November 12, 2010 This archival collection of Boer Prisoners of War provides you the user with a comprehensive 2524 records.

This archival collection of Boer Prisoners of War provides you the user with a comprehensive 2524 records.

These Prisoner of War records will give you a surname, first names, date taken prisoner as well as prisoner number and archival source.

Many of the Boer prisoners of war in the Bermudas were buried on Long Island.

The approximately 17,000 Boer prisoners and exiles in the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) were distributed far and wide throughout the world. They can be divided into three categories: prisoners of war, ‘undesirables’ and internees. Prisoners of war consisted exclusively of burghers captured while under arms. ‘Undesirables’ were men and women of the Cape Colony who sympathised with the orange Free State and Transvaal Republics at war with Britain and who were therefore considered undesirable by the British. The internees were burghers and their families who had withdrawn across the frontier to Lourenço Marques at Komatipoort before the advancing British forces and had finally arrived in Portugal, where they were interned.

Prisoners of war were detained in the Bermudas on Darrell’s, Tucker’s, Morgan’s, Burtt’s and Hawkins’ Islands; In the Bermudas, on St. Helena and in South Africa quarters consisted chiefly of tents and shanties patched together from tin plate, corrugated iron sheeting, and sacking, and in India and Ceylon mostly of large sheds of corrugated iron sheeting, bamboo and reeds. The exiles, whose ages varied between 18 and 82 years, occupied themselves in various fields, such as church activities, cultural and educational works, sports, trade, and even printing, and nearly all of them to a greater or lesser extent took part in the making of curios.

Deneys Reitz

September 16, 2010

Deneys Reitz was born in Bloemfontein on the 2nd April 1882 and died in London, England on 19th October 1944.

He was a cabinet minister, author and soldier, was the third of five sons, his mother, Blanka Thesen, a member of a Norwegian family, of Knysna, being the first wife of Francis William Reitz,* chief justice and afterwards president of the O.F.S. Reitz was given the family name of his paternal grandmother, Cornelia Magdalena Deneys.

He was educated in Bloemfontein. At the outbreak of the Second Anglo-Boer War he joined the Boer forces at the age of seventeen, saw service at Ladysmith, and accompanied Gen. J. C. Smuts* on his famous raid in the Cape Colony (1901-02), of which it, in 1929, wrote a stirring account in his autobiography, Commando. Refusing to take the oath of allegiance at the end of the war, he endured three harsh years abroad, mainly in Madagascar, but was persuaded by Mrs J. C. Smuts to return in 1905, and in 1908 established himself as an attorney in Heilbron.

During the First World War he served on Smuts’s staff in German South-West Africa, and in German East Africa commanded the Fourth South African Horse. Going overseas in 1917, he was twice severely wounded on the western front, was mentioned in dispatches, and ended the war a colonel commanding a battalion of the First Royal Scots fusiliers.

On his return to South Africa he, in 1919, married Leila Agnes Buissiné Wright (1887-1959), of Wynberg, who subsequently became the first woman member of parliament in South Africa. They had two sons.

Entering politics as a member of the South African party, R. represented Bloemfontein South in 1920, and, a few months later, Port Elizabeth, having been ousted in a general election by Dr Colin Steyn.* Subsequently, in 1929, he represented Barberton. Though he lacked the benefits of an advanced education, Deneys through experience and sheer force of personality, proved a good debater. Appointed to the Smuts cabinet, he, as minister of lands, introduced legislation relating to several important projects, notably the establishment of the Kruger national park.He had a son called Francis William who was a farmer in Swellendam.

Out of office from 1924 to 1933, Reitz joined a firm of Johannesburg solicitors and, both personally and on business, travelled widely, visiting the Rhodesias, the Belgian Congo, and, more especially, the Kaokoveld in South-West Africa. It was then, in 1929, that he wrote Commando, the first of his literary successes.

Back in office in 1933, he was appointed minister of lands as a member of Gen. J. B. M. Hertzog’s* coalition cabinet, subsequently be-coming minister of agriculture and forestry in 1935 and minister of mines in 1938. From 1939 to 1943 he was minister of native affairs and deputy prime minister in Smuts’s war-time cabinet. In 1943 he went to London as high commissioner for South Africa, an office that he held until his death in 1944. In South Africa he was regarded as an enterprising cabinet minister, and in the United Kingdom as an admirable representative of the Union of South Africa.

Publication of Commando was followed by that of Trekking on in 1933, and of No outspan in 1943. The first two narratives end with the First World War; the third, a lively mixture of history, politics, travel and sports, covers the next twenty-five years. All three were marked successes, Trekking on achieving a reception as enthusiastic as that of Commando. Both were regarded as classics of adventure, not merely because of their stirring themes, but because of the personality of the narrator and a forthright sincerity of style that matches admirably its material.

Footnotes:

DENEYS REITZ, Commando. Lond., 1929; Trekking on. Lond., 1933; No outspan. Lond., 1934; – Obituaries; The Cape Times, 20.10.1944; Afr. World, 21.10.1944; 28.10.1944 (memorial service and tributes); Forum, 28.10.1944; Jour. S.A. Forestry Assn., Dec. 1944 (port.); – W.w.W. 1941.1950. Lond., 1952; – D.N.B. 1941-1950. Oxf., 1959; – CONRAD HJALMAR REITZ, The Reitz family: a bibliography. School of librarianship, U.C.T. C.T., 1962.

DF Malan

May 27, 2010 Daniel Francois Malan born at Allesverloren, near Riebeek West on 22nd May 1874 and died at 'Morewag', Stellenbosch on 7th February 1959, statesman, church and cultural leader, was the second child in a family of four sons and two daughters. His parents were Daniël François Malan (12.6.1844 – 22.9.1908) and Anna Magdalena du Toit (5.5.1847-12.6.1893), both of whom came from the Wellington district and were descendants of the French Huguenots. After living in the Wamakersvallei they settled on the farm Allesverloren in January 1872, where they were friends and neighbours of the parents of Jan C. Smuts.*

Daniel Francois Malan born at Allesverloren, near Riebeek West on 22nd May 1874 and died at 'Morewag', Stellenbosch on 7th February 1959, statesman, church and cultural leader, was the second child in a family of four sons and two daughters. His parents were Daniël François Malan (12.6.1844 – 22.9.1908) and Anna Magdalena du Toit (5.5.1847-12.6.1893), both of whom came from the Wellington district and were descendants of the French Huguenots. After living in the Wamakersvallei they settled on the farm Allesverloren in January 1872, where they were friends and neighbours of the parents of Jan C. Smuts.*

Malan's father was a well-to-do and respected farmer and churchman and an influential sup-porter of the Afrikanerbond. His mother, from whom he inherited his more striking traits of character and appearance, was a calm, lovable woman of few words but of equable temperament and sound judgement.

He went to school in Riebeek West, where the youthful T. C. Stoffberg* taught him and exercised a profound and enduring influence on him. His progress at school was, however, hampered by myopia and physical frailty. He was an average student and attained the School Higher Certificate in 1890. Realizing that he was not destined to be a farmer, his parents in 1891 sent him to Stellenbosch, where he obtained the Intermediate Certificate at the Victoria College. After his mother's death in 1893 his father married Esther Fourie of Beaufort West, who had a notable influence upon the young M.

Education

Having obtained a B.A. degree in 1895 he decided to become a minister of religion, and in 1896 he completed the Admission Course required for entrance to the Theological Seminary. Although as a student at the Victoria College he was rather aloof and uncommunicative, he was nevertheless methodical and disciplined. He did not take part in organized sport but enjoyed walking and debating.

At the invitation of J. C. Smuts, with whom he had often come into contact on his parents' farm when they were children, M. upon his arrival in Stellenbosch became a member of the Union Debating Society, of which he was chair-man in 1897 and 1899. He was also on the editorial staff of The Stellenbosch Students' Annual. An interesting article which he wrote entitled 'Our Situation' and dealing with the disquieting materialistic spirit of the times, appeared in the society's journal, in 1896.

In the same year M. taught for a term in Swellendam, after which he began his studies at the seminary, simultaneously enrolling at the college for the M.A. course in Philosophy, a degree he obtained towards the middle of 1899. As a student at the seminary he was strongly influenced by the devout example and inspiring lectures of Professor N. J. Hofmeyr.*

In the second half of 1900 he wrote the Candidates' Examination and left for Utrecht, Holland, in September to continue his theological studies. There he was greatly impressed by Professor J. J. P. Valeton, a leading exponent of the doctrines of the 'ethical school' in Theology, which accepted the Bible as a given reality without further argument.

When President S. J. P. Kruger* stopped over in Utrecht in December 1900 on his journey to The Hague and received an overwhelming ovation, M. was also present, and in January 1901 visited him in his hotel in Utrecht.

While he was a student in Utrecht M. under-took various journeys on the Continent and to England and Scotland, and in August 1902 re-presented South Africa at the world conference of the Students' Christian Association in Soro, Denmark. He also became acquainted with the aged Dutch theologian and poet Nicolaas Beets, who had a lasting influence on him.

M. was also much impressed by the visit which the Boer Generals, Louis Botha,* C. R. de Wet* and J. H. de la Rey,* paid to President Kruger in Utrecht on his birthday on 10.10.1902. He made several calls on President and Mrs M. T. Steyn* who were staying in Germany, and a firm friend-ship arose between them. Steyn fundamentally influenced his opinions on political and cultural matters both then and later.

Political Life

From then on he kept abreast of developments in the political and cultural life of South Africa and grew concerned about the submission and conciliatory attitude of some Afrikaners towards their political opponents after the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) had ended. In April 1904 he addressed two very illuminating letters to the editor of the Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant in which he expounded his view of the South African situation; he dealt in particular with the significance and power that were inherent in the Afrikaner's language and Afrikaner unity as a potential safeguard against Anglicization. These two aspects of Afrikaner identity were developed and formulated in a manner both arresting and, considering the political and cultural background of 1904, surprising. It was the first indication of M.'s extra-ordinary ability to put an idea on paper and convey it to others. These letters show that as early as 1904 M.'s views on the political and cultural situation in South Africa had assumed a definite shape.

On 20.1.1905 he became a Doctor of Divinity, with a thesis on Het idealisme van Berkeley (The Idealism of Berkeley), and in May, at the age of thirty-one, he was formally admitted to the ministry in Cape Town. At the invitation of the Reverend A. J. Louw* of Heidelberg, Transvaal, he was ordained on 29.7.1905 as an assistant preacher of the N.G. Kerk in that town, and for the first time came into contact with many people who still bore the physical and economic scars of the Second Anglo-Boer War. At the same time he became deeply aware of his bond with his people and of the necessity for them to close their ranks and stop niggling over principles, since this could endanger the preservation of the Afrikaner's identity.

After spending about six months in Heidelberg, M. having in 1905 accepted a call to Montagu was inducted on 16 2.1906, and there during his six-year stay began to apply himself to the problem of uplifting the impoverished Afrikaner. At the congregational level his main preoccupation was with mission work and poor-relief, and he maintained that the extent to which its people undertook such work determined the spiritual climate of a congregation.

It was as early as the first decade of this century, while serving the congregation of Montagu, that M. began to come to the fore as an academic, cultural and potential political leader. During the Synods of 1906 and 1909 he emphasized the fundamental importance of training Afrikaner teachers and advocated that a national educational ideal should be formulated. In August 1908, as general chairman of the Afrikaanse Taalvereniging, he made his famous plea for the recognition of Afrikaans as a written language, and in 1909 was active as a founder of De Zuid-Afrikaanse Akademie voor Taal, Letteren en Kunst (The South African Academy for Language, Literature and Art). At the Stu-dents Language Conference in Stellenbosch in April 1911 he delivered his inspiring address on 'Language and nationality'.

M. was also preoccupied with the idea of unity in the ecclesiastical field. During the Synod of 1909 he delivered a strong plea for closer links between the N.G. Kerke of the four colonies and represented the Cape Church in De Federale Raad der Kerken (Federal Council of Churches). He was the driving force behind the campaign for a church association, which, however, foundered in 1912 and became a reality only fifty years later in 1962, after his death.

The Spiritual Side

Of far-reaching importance for both the N.G. Kerk in the Union and the spiritual and cultural interests of the 'exiles', was the extended tour he undertook at the request of the Cape Church between July and November 1912. The object of this was to visit the congregations in Northern and Southern Rhodesia. The diary of his travels published in instalments in De Kerkbode and later in book form under the title Naar Congoland (infra), was extensively read and aroused widespread interest in the welfare of the Afrikaners in Rhodesia.

On 1.2.1913 M. became assistant preacher to the congregation of Graaff-Reinet, this being the year in which the estrangement between the Prime Minister, General Louis Botha, and General J. B. M. Hertzog* reached a crisis. M. was in sympathy with Hertzog's standpoint which was pro-South African in contrast to that of Botha whose policy was to conciliate Britain and the English-speaking population. He voiced his share in the church's opposition to the plans of the government, which aimed to establish an English-orientated teaching university for both language groups in Cape Town, and zealously strove to have the status of the Victoria College at Stellenbosch raised to that of a fully fledged national university. This goal was realized through legislation in 1916.

The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 shortly afterwards led to the unfortunate Rebellion in South Africa and to unhappy division and confusion among the Afrikaners, in the ecclesiastical as well as in other spheres. M., who was staying in Pretoria during the week-end of 18 to 20 December, tried in vain as one of a six-man deputation to obtain clemency for Commandant Jopie Fourie* who had been sentenced to death. When it seemed that the Rebellion with all its attendant bitterness would cause a schism in the N.G. Kerk, M. provided powerful leadership at the critical 'Ministers' Conference held in Bloemfontein in January 1915.

In 1914 the National Party (N.P.) was founded under the leadership of General Hertzog. The need for an influential newspaper to serve as a mouthpiece for the party led to the establishment of De Nationale Pers Beperkt at Stellenbosch, and through the mediation of W. A. Hofmeyr* in particular M. was earnestly re-quested to become editor of the newspaper. After seeking the advice of prominent politicians and church leaders he accepted the post and on 13.6.1915 delivered his farewell sermon to the congregation of Graaff-Reinet. The first issue of De Burger appeared on 26.7.1915. Since at a conference at Cradock in June 1915 M. had already been elected to the executive of the National Party, in practice he combined the editorship of De Burger and the leadership of the National Party in the Cape. As editor from 1915 to 1923, his editorials, written in a graceful, dignified style, gave direction to the national aspirations of the Afrikaner. De Burger rapidly gained wide respect in the world of journalism and an unusual status, despite its unenviable role in the war situation.

The Afrikaner's republican aspirations and South Africa's right to leave the British Empire often formed the core of M.'s editorials. His views played an important part in formulating party policy; this was particularly so after his election as chairman (and thus unofficial leader of the party in the Cape) at the Middelburg congress of the National Party in September 1915. Three months after leaving the service of the church M. was not only in the thick of politics but in the midst of the crisis with which the First World War (1914-18) and the Rebellion (1914) confronted the Afrikaner.

Influential leaders within the National Party were now anxious that M. should obtain a seat in the House of Assembly as soon as possible. Although he failed twice, first in Cradock in 1915 and then in Victoria West in 1917, in 1919 he became M.P. for Calvinia and retained this seat until 1938. Thereafter he represented the constituency of Piketberg until he retired from politics.

After the First World War the leaders of the National Party, encouraged by the statements of the Allied leaders, particularly the American President Woodrow Wilson and the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George,* on 'the right of self-determination of small nations', decided to send a delegation to the peace conference in Paris; its object would be to plead that the independence of the two former Boer republics should be restored. If this failed, greater constitutional independence for the Union of South Africa would be requested. M. and Advocate F. W. Beyers* represented the Cape in the 'Freedom Deputation' of 1919, which was led by General Hertzog. When the delegation returned without having accomplished anything, M. found that there was a strong desire for reunification among the Afrikaans-speaking people and he consequently began to direct his energies to-wards realizing this ideal. The right of nations to self-determination and the resultant Nationalist claim that the Union should have the right to secede from the British Empire became the major campaign issue in the so-called secession election of 1920. It resulted in a political stale-mate, and after an abortive attempt by Smuts to form a coalition government the Unionist Party disbanded and threw in their lot with the South African Party. A new election in February 1921 gave Smuts a healthy majority, but only threeand-a-half years later his government was defeated through an election agreement between General Hertzog and F. H. P. Creswell,* leader of the Labour Party. M. saw this as a partial victory for the reunion movement to welcome all those who loved their country.

In the cabinet which General Hertzog formed as Prime Minister, M. became Minister of Internal Affairs, Education and Public Health. Although not Deputy Prime Minister (this post was first occupied by Advocate Tielman Roos* and then by N. C. Havenga*), M. nevertheless became a prominent member of the cabinet. In government circles he was regarded as a farsighted political strategist and as such he moved into the forefront. He distinguished himself as an extraordinarily accomplished parliamentarian, an indomitable fighter and an unequalled debater. As a minister he gained a reputation for competent administration and unmitigated hard work, while in the various government departments under his control he was noted for his informed approach.

Among the most important bills which he piloted through parliament in the Pact Government, and in which he was strongly supported by Senator C. J. Langenhoven,* was the amendment to the Union Constitution (1925); in terms of this Afrikaans was recognized as an official language. This decision, which was unanimously carried in parliament, represented the fulfilment of the ideal for which M. had striven for twenty years. In addition he implemented the policy of bilingualism in the public service, over-hauled the public service administration and used the opportunity of obtaining improved facilities and greater financial support for higher and technical education. Immigration from certain countries was limited by means of the quota system. As regards the Indians M. acted in 1927 as chairman of the notable Cape Town conference between representatives of the South African and Indian governments; here he insisted that South Africa should give more generous financial assistance to Indians who wished to leave the Union of their own free will. In order to overcome the stalemate between the House of Assembly and the Senate (in which the opposition was in the majority), M., aided by a joint sitting of both Houses, piloted the Amendment Act on the Composition of the Senate through parliament. In terms of this the governor-general could dissolve the Senate within twelve days after a general election.

Between 1925 and 1927 M., who was the minister responsible, also handled the very delicate negotiations over the bill on South African citizenship and a national flag. The latter was introduced by M. during the parliamentary session of 1925, but was shortly after-wards withdrawn; this was in order to obtain a greater measure of co-operation from the other party, and also because General Smuts had come out in support of the principle. The following year, on 25.5.1926, M. introduced a similar bill, but the difference of opinions between the government and the opposition appeared to be so profound that he withdrew his proposal. Meanwhile a tremendous battle was in progress over this issue both outside parliament and within the Nationalist ranks. Two groups opposed the Nationalists : one wanted nothing but the preservation of the British flag, whereas the other was prepared to accept a new flag provided the Union Jack had a prominent place in it. Even among the Nationalists themselves there were serious differences of opinion. M. was not prepared to make any concessions, while the Prime Minister, encouraged by N. C. Havenga and Tielman Roos, was willing to make concessions to the opposing party. After many discussions the matter was referred to a Select Committee in 1926 and General Hertzog now took the matter in hand himself, M. retreating further and further into the background. Many Nationalists were disappointed that the Union Jack would appear in the Union flag. M. resigned himself to the position because he did not want to cause a schism in the ranks of the National Party. Accordingly he once again submitted a bill in this connection. It was passed on 23.6.1927 and the Union flag was officially hoisted for the first time on 31.5.1928. In the flag issue M. had taken the lead in creating the generally accepted symbol of nationhood and independence, but the struggle had indicated that there was no longer complete unanimity within the ranks of the National Party. A certain amount of estrangement and even mistrust among leading Nationalists had crept in.

After the election of June 1929, which this time brought the Nationalists to power with a clear majority, M. retained his portfolios. In 1930 he played a leading role in gaining White women the vote and placing the general election qualifications on an equal footing in all four provinces.

With the decline of the Labour Party, ally of the National Party, as well as internal squabbles within the party itself, in which Tielman Roos and a republican section were particularly involved, a gradual weakening of the governing party occurred. Moreover, a world-wide economic depression hit South Africa and was accompanied by a devastating drought. When Britain dropped the gold standard in September 1931, Tielman Roos, who had been appointed Appeal Judge in 1929, stormed into the political arena once again towards the end of 1932. His avowed aim was to get South Africa off the gold standard and bring about a coalition. The government was compelled to depart from its professed policy and drop the gold standard. The National Party now entered a period of crisis in its history. Hertzog and M. refused to accept Roos, but after strenuous political negotiations behind the scenes the Prime Minister in February 1933 declared himself willing to accept Smuts's offer of a coalition government.

M. displayed little enthusiasm for this move because he feared that it would jeopardise the Afrikaner's interests. Nevertheless he stood as a Coalition candidate for the election of May 1933, in which the Coalition parties achieved an overwhelming victory, but he refused to serve in the Coalition cabinet, although he continued to support Hertzog. He was opposed to further rapprochment between the National and South African Parties, for he feared that closer co-operation between them represented a threat to the principles and policy of his party.

After the election of 1933 a nation-wide movement arose to consolidate the existing political co-operation into an enduring fusion of the two parties. Time and again M. sounded a warning note and at the Cape congress of the National Party in October 1933 he asserted: 'Reunion means bringing together those who belong together by virtue of political conviction and this rules out the fusion of parties'. M. was convinced that fusion could not succeed, since en-during unity could not be cemented while Hertzog and Smuts differed basically over principles such as the divisibility of the crown, the right to remain neutral and the sovereign status of the Union. The Cape congress followed M.'s lead and he was now diametrically opposed to Hertzog, although negotiations between them continued. However, Nationalists in the other provinces ranged themselves behind Hertzog; thus the fusion of the National and South African Parties became an accomplished fact. The United South African National Party came into being on 5.12.1934, while the Cape National Party, led by M., maintained its identity. M., with eighteen followers, became the National opposition in the House of Assembly.

The years 1934-39 constituted a low ebb in the history of the National Party, but M. enjoyed the support of most Nationalist-orientated people in the Cape and leaned heavily on the influential Nasionale Pers. In addition, he had the efficient party organization in the Cape at his disposal. In these years the strife between the Fusionists and the Purified National Party was relentlessly sharp and often heated. It was expressed in the 1937 report of a Commission on the Coloured franchise which recommended that the Coloureds in all four provinces be granted the vote and that they be placed on the common voters' roll. Raising serious objections to this M. and his party demanded the political and residential segregation of the Coloureds. Another major bone of contention was the question of a republic, which for tactical reasons Hertzog had dropped for the time being since he did not regard it as practical policy, though the National Party was gradually moving in this direction. However, on the question of whether South Africa could remain neutral if Britain were to become involved in a war, Hertzog and M. did not disagree.

In the general election of 1938 the Nationalists increased the number of their seats in the House of Assembly to a still modest twenty-seven. The 247 000 votes this party acquired, as opposed to the 448 000 of the United Party, served as great encouragement to the National Party. Moreover, M. realised that time was on its side since it was clear to him that there was already a serious rift between Hertzog and Smuts over certain fundamental issues. The year 1938 was also the year of the Voortrekker Centenary and the Symbolic Ox-waggon Trek which served as a strong stimulus to the awakening of Afrikaner nationalism. It was at about this time that cultural societies became active and the Reddingsdaadbond did a great deal for the impoverished Afrikaner. In 1938 the Ossewa-Brandwag also came into being – a cultural organization aimed at strengthening the newly awakened enthusiasm for the Afrikaner cause. However, within two years it began to enter the political arena, making propaganda for republican government and later, during the war, even for a totalitarian state.

When the Second World War broke out on 3.9.1939 and it became known that the cabinet was divided on the question of South Africa's participation, M. immediately offered Hertzog his support in writing should he adopt a neutrality stand in parliament. On the next day M. took part in the parliamentary debate on this matter, supported Hertzog's neutrality motion and declared that in terms of the Statute of Westminster and the Status Act, South Africa had the right to remain neutral. If South Africa aided Britain because she had moral ties with that country, she would, according to M., be a country of slavery which no longer had its destiny in its own hands. Hertzog's neutrality motion, supported by M. and his followers, was nevertheless defeated by thirteen votes in the House of Assembly and Hertzog resigned as Prime Minister. A few days later ten thousand anti-war demonstrators met at Monumentkoppie near Pretoria to honour Hertzog and M. who became 'reconciled' there. From this moment on M. renewed his efforts to effect the reunion of all Afrikaners who were obliged by the declaration of war to leave their party and seek a new refuge. These were Nationalists who were still his supporters, and Hertzog's United Party followers. However, mutual distrust rendered his task very difficult.

In January 1940 the 'Herenigde Nasionale Party of Volksparty' (H.N.P. of V.) came into being, in which the followers of Malan and Hertzog found a political home and in which the republican ideal was incorporated in the programme of principles. Although M. was willing to give up the leadership of the new party to Hertzog, on 6.11.1940 the latter retired from politics owing to conflicting views, and in April 1941 M. became the leader of the H.N.P. of V.

The years from 1941 to 1943 were the bitterest and most difficult period of his political career. He not only had to contend with a divided Afrikanerdom but felt, as he had done thirty years before, that it devolved upon him to restore the shattered unity; now he was in the midst of a war-time situation in which he had to endure a great deal of opprobrium from the powerful United Party and its adherents who were in favour of the war. On another front he crossed swords with fellow Afrikaners who though really of the same persuasion envisaged a different approach to the goal of freedom; for instance in 1941, under the leadership of Dr J. F. J. van Rensburg,* the bellicose Ossewa-Brandwag, which had originally supported M. as 'Leader of the People', branched out in another direction and embroiled itself in politics, eventually becoming a threat to the H.N.P. of V. Other dissentient opposition groups such as Advocate Oswald Pirow's* New Order pressed for National Socialism. After Hertzog had retired Havenga, his loyal follower and confidant, formed an organization of his own and called it the Afrikaner Party, while many Afrikaans-speaking people supported General Smuts's war effort. Afrikaners were divided in spirit and for M., to whom Afrikaner unity had become a passion, it was a dark, humiliating time. In August 1941 he found himself compelled to confront the numerically strong Ossewa-Brandwag, from which a growing stream of Nationalists resigned and supported him.

Although in the general war-time election of 1943 M.'s party gained only two more seats, the result was significant, since all the dissenting groups on the 'national' side, which had opposed M. and put up their own candidates, were completely eliminated. This meant that the H.N.P. of V. now formed a united and solid opposition in parliament. Under the circumstances it was a victory for M.'s leadership. Furthermore, the result of the by-election in Wakkerstroom a year later was of far-reaching significance to M. and his followers and a source of consternation to Smuts and his party, since the H.N.P. of V. wrested this constituency from the United Party. Marshalling its forces and improving its organization to a point of unequalled efficiency, the H.N.P. of V. now made intensive preparations for the general election of 1948. M., who realized the necessity for Afrikaner unity if the election was to be won, succeeded in 1947 in concluding an election agreement with Havenga and his Afrikaner Party. This signified the reunion of two wings of Afrikaner Nationalism which had become temporarily estranged. It also brought the hard core of Hertzog supporters back into the arena, which in itself was one of M.'s major achievements as a leader and political strategist.

He concentrated particularly on government policy and measures relating to the racial problem, Communism, the economic interests of the Union, the handling of matters such as health, food and housing and the interests of the returned soldiers. Smuts, on the other hand, was in a strong position as a war hero and inter-national political figure who had reached the zenith of his fame in 1945 and enjoyed a position of unassailable authority in his own party. In the light of the well-known difference in approach to the racial problem between Smuts and his confidant and right-hand man, J. H. Hofmeyr,* M., powerfully supported by the Nationalist newspapers, let slip no opportunity of pointing out this weakness in the government. Thus the racial question, to which M. offered 'apartheid and guardianship' as a solution, be-came the overriding factor in the election. The word 'apartheid' had already been coined by a party member, but it was M. who formulated the policy attached to the word and gave it meaning.

The outcome of the election of 26.5.1948 was a great surprise because the H.N.P. of V. gained seventy seats and the Afrikaner Party nine, a total of seventy-nine. This gave M. and Havenga a majority of five over the United Party, the Labourites and the three Native representatives combined. Smuts called the result a freak, while M. termed it a miracle of God.

When at the age of seventy-four M. became the fourth Prime Minister of the Union, every-one considered this achievement a personal triumph. He formed a cabinet which, for the first time in history, consisted exclusively of Afrikaans-speaking persons; it was, at the same time, also the first to be fully bilingual. Havenga became Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance.

The first five years of M.'s premiership were exceptionally stormy. He was continually attacked by his political opponents abroad and at home, particularly by the powerful opposition press. In addition the H.N.P. of V. in spite of the election results found itself in a vulnerable position, being in the minority in the Senate. M. was, however, determined to remain in power and the H.N.P. of V., aided by the deciding vote of the president of the Senate, did on a number of occasions succeed in getting its programme of legislation through. In 1949 M. achieved the measure which gave South-West Africa six members in the House of Assembly and four senators in the Union parliament. The election of 30.8.1950 in South-West Africa was won by the Nationalists in all six constituencies and the position of the H.N.P. of V. in the Senate was greatly strengthened by the election of two Nationalist senators and the appointment of another two for South-West Africa. But the closer links between South-West Africa and the Union meant that the Malan government be-came embroiled in a continual struggle with the United Nations.

The question of incorporating the British protectorates in the Union, previously raised by a South African government, was taken up again by M. but rejected by the British government.

Since at this juncture there were no real differences of principle between the H.N.P. of V. and the Afrikaner Party, M. and Havenga decided in August 1951 to fuse them. It was undoubtedly M.'s confidence in and respect for Havenga which rendered this fusion possible. Once again known as the 'National Party' (N.P.), this was the name which had served to unite those of national sentiments between 1914 and 1940, and was another milestone in M.'s struggle to 'bring together those who belong together by inner conviction'.

M. came to power at a fortunate time from an economic point of view. In July 1949, with the consent of the International Monetary Fund and the Union Treasury, the gold mines were allowed to sell a limited amount of gold at higher prices than the then prevailing sum of thirty-five dollars per ounce. On 19.9.1949 M. devalued the Union's rate of exchange, by which the price of gold in sterling rose from 172s. 6d. per ounce to 248s. 2d. The resulting economic revival and industrial expansion made the Malan regime more acceptable to the general public.

Legislation submitted by his government between 1948 and 1953 was fought tooth and nail and sometimes clause by clause by the United Party and its press. Nevertheless the government succeeded in placing various radical measures on the statute books: the right of appeal to the British Privy Council was abolished; through the Population Registration Act all people over the age of sixteen were classified and registered as White, Coloured, Bantu or Asiatic and issued with identity cards; through the Group Areas Act the government was em-powered to reserve certain parts as residential areas for specific population groups; the act which forbade mixed marriages (between Whites and Non-Whites) and the Suppression of Communism Act were adopted as had been promised in the election (this act, among other things, declared the Communist Party in South Africa an illegal organization, membership of which would be punishable by up to ten years' imprisonment); the Immorality Act was passed and in terms of the Union Citizenship Act dual citizenship (that of Britain and the Union of South Africa) was discontinued and replaced by South African only. With the passing of the Public Holidays Act, Van Riebeeck Day, 6 April, and Kruger Day, 10 October, became national holidays and through the adoption of three important Bantu acts the influx of Bantu into the urban areas was controlled, provision being made for essential services in Bantu townships.

At the Commonwealth Conference of 1949 M. made an important contribution towards gaining Commonwealth members the right to adopt a republican form of government, while the adjective 'British' was no longer used to describe the Commonwealth. In the same year M. piloted the Citizenship Act (Act 44 of 1949) through parliament. In terms of this a British subject was to reside in the Union for four years (it had previously been two) before he could obtain Union citizenship; this in any event depended on the registration certificate which the Minister of Internal Affairs might or might not issue. Four years later M. also amended the royal title attached to the Union by giving it a purely South African character, thus distinguishing it from the titles used by other members of the Commonwealth. It was to be Elizabeth II, Queen of the Union of South Africa and of Her Other Kingdoms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth.

On the series of apartheid measures introduced by the Malan government, that which was em-bodied in the Separate Representation of Voters Act in 1951 was most vehemently attacked by the opposition. In terms of this the Coloureds were taken off the common voters' roll and placed on a separate one. This legislation gave rise to a protracted constitutional crisis in which the question of the sovereignty of parliament was involved. M. attempted to solve the problem by means of legislation which would make parliament a 'High Court' for purposes of Coloured representation, but the attempt failed. His own followers were unhappy about the method employed and there was serious criticism of the measure from both the opposition and the National Party itself, while a court decision declared the method invalid as a constitutional solution. To this M. replied that he accepted the Court of Appeal decision provisionally, but that he would take the matter to the voters in the next election. Meanwhile, the apartheid and anti-communist legislation of the Malan government paved the way for a resistance movement, the 'Torch Commando', and for demonstrations and the threat of strikes, but M. refused to be intimidated.

The results of the 1953 election strengthened the government's hand considerably, since M. now had a majority of twenty-nine (excluding the Speaker) in the House of Assembly. In the light of his statement, before the election, on the decision of the supreme court, M. regarded the election results as a mandate to implement his party's racial policy.

During the first parliamentary session after the election M. tried in vain, by joint sittings of both Houses, to re-enact the Separate Representation of Voters Act, to place the sovereignty of parliament beyond all doubt and to declare the testing right of the courts invalid.

After the election of 1953 he left for London where he attended the coronation of Queen Elizabeth I.I and the Commonwealth Conference. He also paid a highly successful visit to Israel. In fact by 1953 M. was a far less controversial figure both in South Africa and abroad than he had formerly been. His stature as a statesman had increased and he compelled respect in circles other than those of his political supporters. His leadership was confirmed once and for all by the great victory won by the National Party in the general provincial elections of August 1954. After resigning as leader of the Nationalists in the Cape in November 1953, M. astonished the country on 11.10.1956 with the dramatic announcement of his intention to retire from politics altogether on 30 November. He himself would have preferred Havenga to Advocate J. G. Strijdom as his successor; this was mostly out of personal loyalty to Havenga and the fact that he was Deputy Prime Minister. But on 30 November the party caucus designated Strijdom as the new Prime Minister.

After his retirement M. settled at Stellenbosch where he began writing his autobiography, which he was unable to complete because of two strokes in 1958 which partially paralyzed him. After his death the work was completed by his friends. He died at his home after suffering another stroke and was buried in the Stellenbosch cemetery.

M. was the successor to the Generals in South African politics. Since he devoted his life to the study of Theology and Political Science his absorption in these subjects had a considerable influence on his career and outlook, and throughout his life he was the champion of Afrikaans culture and Afrikaner nationalism. His leadership and personal example were an inspiration to the Afrikaner people.

As early as 1915 it had become a passion with him to heal the schism among Afrikaners, and the political division at intervals among the Nationalists frequently placed him in the fore-front of reconciliation and reunion movements. He defined his credo for national unity in the exhortation, 'Bring together those who belong together by inner conviction'. Moreover, he considered a republic, free of constitutional ties with Britain, essential to amalgamate the two White language groups into one nationally conscious people.

While still a member of the opposition M. had a considerable influence on South African politics. His power lay in his objectivity, patience and remarkable administrative ability, added to a gift of extraordinary eloquence, which evinced itself early in his career. He had a deep, sonorous voice, his preparation was thorough, his logic impeccable. These things, added to his powers of persuasion and impressive personality on a platform, contributed to make him one of the greatest orators in South African parliamentary history. M. was a true democrat who would not act unless he was sure of the feelings of the Afrikaner people, from whose response his leadership grew spontaneously. At no stage did he attempt to force it upon them.

As a man he was imperturbable, and although outwardly he was aloof and reserved his friends and relatives found in him a warm humanity and a spontaneous sense of humour. In his public actions he seldom betrayed his feelings and moods and consequently cartoons in opposition newspapers often depicted him as a sphinx.

He was of average height and after 1920 developed a burly physique. When he was a clergy-man he cultivated a heavy, dark moustache. He went bald at an early age and wore spectacles with very thick lenses all his life.

The University of Stellenbosch, of which he was chancellor from 1941 to 1959, awarded him an honorary doctorate, as did the University of Pretoria and the University of Cape Town.

M.'s publications include the following: Het idealisme van Berkeley (1905); Naar Congoland (1913) and Afrikaner-volkseenheid (1959). A volume comprising thirty of his most famous speeches appeared in 1964 under the title Glo in 'n yolk, edited by S. W. Pienaar and J. J. J. Scholtz.

In 1926 M. married Martha Margaretha Elizabeth van Tonder (nee Zandberg), and they had two sons. She died in 1930 and in 1937 he married Maria-Anne Sophia Louw (t1973) of Calvinia. This marriage was childless, but in 1948 they adopted a German orphan girl.

The best portraits of M. were painted by G. Wylde and I. Henkel. That by Wylde hangs in the Parliamentary Buildings, while Henkel's was in the possession of Mrs Malan and hung in their home 'Môrewag' in Stellenbosch. Of the busts of him by Coert Steynberg and Henkel, Steynberg's is in the possession of the University of Stellenbosch. There are four copies of the striking Henkel bust, one of which is in the D. F. Malan Museum of Stellenbosch University and another in Parliament Buildings, Cape Town.

The D. F. Malan Museum in the Carnegie Library, University of Stellenbosch, was opened in 1967. It consists of a museum section, an exact replica of M.'s study at 'Morewag', and a well arranged archive section. When his hundredth birthday was commemorated on 22.5.1974, the D. F. Malan Centre at the University of Stellenbosch was opened.

Boer Nostradamus

April 15, 2010 Nicolaas Pieter Johannes Jansen (Siener) Van Rensburg born at *Rietkuil, Wolmaransstad dist., 30.8.1864 – †Rietkuil, Wolmaransstad dist., 11.3.1926), Boer clairvoyant, was the son of Willem Jacobus and Anna Catherina van Rensburg. Van R. was taught to read and write by his mother and had his first ‘vision’ at the age of seven, when he assuaged her fears that an attack would be made by the farm-workers during her husband’s absence.

Nicolaas Pieter Johannes Jansen (Siener) Van Rensburg born at *Rietkuil, Wolmaransstad dist., 30.8.1864 – †Rietkuil, Wolmaransstad dist., 11.3.1926), Boer clairvoyant, was the son of Willem Jacobus and Anna Catherina van Rensburg. Van R. was taught to read and write by his mother and had his first ‘vision’ at the age of seven, when he assuaged her fears that an attack would be made by the farm-workers during her husband’s absence.

When he was eighteen he and his brothers took part (1882) in an expedition led by Gen. P.J. Joubert * against Nyabêla *. Van R. contracted malaria during this campaign, which lasted from 30.10.1882 to 10.7.1883, and his health suffered a temporary setback.

He gained renown as a clairvoyant during his lifetime and particularly during the Second Anglo-Boer War (1889-1902) and the Rebellion of 1914. On the outbreak of the war (11.10.1899) he was generally known as ‘Oom Niklaas’, although he was only thirty-five at the time. He served mainly under General J.H. de la Rey* and it was after the battle of Kraaipan (12-13.10.1899) in the vicinity of Taungs, while De la Rey’s commando was on its way to Kimberley, that he had his famous vision of war. He saw fleeing women and scorched earth, and the vision affected him so much that when he was found under a sage bush the next day his wild eyes and dishevelled hair bore witness to the spiritual torment he had undergone.

He spent a brief period in hospital at Boshof for treatment of a septic wound in his hand before joining General P.A. Cronjé’s commandos, and was lucky enough to escape when Cronjé surrendered on 27.2.1900. After roaming about for a time, Van R. joined up with De la Rey’s commandos once more. He fought in the battle of Ysterspruit near Klerksdorp on 28.2.1902, and from a vision of ‘the Red Bull wounded and defeated’ predicted De la Rey’s famous victory over Lord Methuen’s forces at the battle of Tweebos (7.3.1902). It is said that one of Van R.’s forecasts had prevented the capture of General J.B.M. Hertzog* and W.J.C. Brebner* at the end of February that year. Shortly after this his vision of a great assembly of waggons was interpreted as the conclusion of the peace treaty. He had numerous visions after the war, but for him the most terrifying was the one in which he saw General De la Rey’s death and burial.

Van R. participated in the Rebellion towards the end of 1914 and accompanied the commando under General J.C.G. Kemp which was to join forces with General S.G. (Manie) Maritz*. The rebel commando engaged the government forces at Kuruman on 8.11.1914. Shortly afterwards he was captured and spent the major part of 1915 in prison with Harm Oost* and other rebels. He foresaw his release from prison on 20.12.1915 a few days before it occurred. Back on his farm ‘Rietkuil’ he continued to have visions, those concerning the influenza epidemic (October 1918) and the death of General Louis Botha on 27.8.1919 being the most important.

Van R. became a legendary national figure. His fellow-citizens and some of the military officers interpreted his visions as events which would assail their people in the future. Many of his predictions were recorded and spread throughout the country and some even related to the Second World War (1939-45). He himself never interpreted his own prophecies.

A small, retiring man of frail physique, Van R. was buried on his farm two days after his death. On 8.1.1884 in Potchefstroom the Reverend Dirk van der Hoff* had married him to Anna Sophia Kruger. They had four sons and six daughters, but there is no grandson to carry on the family name.

A marble bust of Van R.’s face by Fanie Eloff* is in the possession of Mr H.F. van Broekhuizen of Pretoria and a bronze bust by G. de Leeuw can be seen in the library of the Potchefstroom College of Education. A book in which some of his predictions (15.8.1916-26.1.1926) were recorded by his daughter, Anna Sophia Badenhorst, and objects made by Van R. during his imprisonment are kept in the S.P. Engelbrecht Museum of the NH Kerk in Pretoria. A photograph of Van R. appears in SESA (infra). Z. L. PRETORIUS

Footnotes: *

Transvaal Arch., Pta.: Estate no. 59760; – J. J. VAN DER WESTHUIZEN. ‘Collected prophecies of Seer van Rensburg’ in Arch. of the history of the Western Transvaal, P.U.; – L. S. AMERY, The Times history of the war in South Africa. 1899-1902. V.4. Lond., 1906; – S. BOTHA. Profeet en krygsman. Die Iewensverhaal van Siener van Rensburg. Jbg., 1941; – G. D. SCHOLTZ, Die Rebellie 1914-1915. Jbg., 1942; – H. OOST, Wie is die skuldiges? Jbg., 1956; – J. MEINTJES, ‘Boodskapper van die onbekende Siener van Rensburg’, Dagbreek, 17.12.1967-31.12.1967; – SESA. V. 11. C.T., 1975; – Private information: Mrs A.S. Badenhorst (daughter), Rietkuil, Ottosdal.

Lambert's Bay Cemetery Images on-line

March 11, 2010 This west coast cemetery provides the resting place of several hundred people. Recently Ancestry24 photographed the entire cemetery of over 400 headstones. This cemetery is easily accessible from the main road and the gates are open most of the time. We felt safe and un-intimidated as we walked around the graves except for a few birds nesting in the sand that were quite scary.

This west coast cemetery provides the resting place of several hundred people. Recently Ancestry24 photographed the entire cemetery of over 400 headstones. This cemetery is easily accessible from the main road and the gates are open most of the time. We felt safe and un-intimidated as we walked around the graves except for a few birds nesting in the sand that were quite scary.

The bay was named after Sir Robert Lambert, commander of the Cape naval station (1820-22), who did survey work here. In 1900′s an incident which is humorously called `the only naval battle of the Boer War’ occurred here when Gen. Hertzog’s men opened fire on the Sybille, which lay at anchor.

The Town. Lambert’s Bay is a fishing town and holiday resort on the west coast, north of St. Helena Bay in the Clanwilliam district and is situated 290 km north of Cape Town and 64 km west of Clanwilliam.

The town was established on the farm Otterdam, which the first registered owner, Robert Grissold. The first residential plots were sold in 1913.

After having successively formed part of the Ned. Geref. parishes of Clanwilliam, Leipoldtville and Graafwater, Lambert’s Bay on 7 Aug. 1957 became an independent congregation, and the year after a congregation for non-Whites was formed. A Swede, Axel Lindstrom, is regarded as the founder of Lambert’s Bay. During the Second Anglo-Boer War he came to South Africa from the U.S.A., established a lobster factory in Cape Town, started the first factory for the canning of lobsters at Lambert’s Bay, and founded the big Lambert’s Bay Canning Company.

Source Acknowedgement: Nasou Via Afrika

Isidore William Schlesinger

June 22, 2009Born in Bowery, New York, U.S.A., 15.9.1871 and died in Johannesburg, 11.3.1949, Schlesinger was a financier and pioneer of the South African entertainment industry. He was the second son of the family of ten of Abraham Schlesinger, a Hungarian-Jewish immigrant. The European branch of the family owned a saw-mill in the Patra mountains on the border of the present Czechoslovakia. Since the mill could not provide a livelihood for the whole family, two brothers, Abraham and Moritz, emigrated to America and started their career by splitting wood, Abraham later going into the cigar business and then opening a bank.Schlesinger grew up on the outskirts of the Bowery, the East Side district of New York, helping, as a boy, to supplement the family income by peddling hair-clips and selling newspapers. By the age of eighteen he was a commission and insurance agent. Having read about the Witwatersrand gold discoveries, he took ship to South Africa in 1894, joining the Equitable Insurance Company (an American concern) in Johannesburg, and becoming a highly successful insurance salesman. Within less than two years Schlesinger rose from a state of abject poverty to affluence, earning more than £1 000 a month commission by tirelessly travelling the length and breadth of the country selling policies, and in this way acquiring an extensive knowledge of South Africa.

Isidore William Schlesinger

Just before the outbreak of the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) the Equitable made him its regional manager in Ireland. He returned to Johannesburg at the end of hostilities to launch a property development enterprise, the African Realty Trust, which, until 1904, developed new residential suburbs in Port Elizabeth (Mount Pleasant) and Johannesburg (Orange Grove, Houghton, and Killarney) by giving salary-earners an opportunity to buy their own homes on an instalment basis.

At the end of 1904 Schlesinger founded his own insurance company, the African Life Assurance Society, which, during its first year of business, sold 2 274 policies valued at more than £I million. As the managing director Schlesinger personally organized the whole company from board-room to stationery cupboard, and coached all canvassers and agents. In 1905 he bought the Robinson South African Bank (founded by J. B. Robinson), which had run into financial difficulties, converting it into the Colonial Banking and Trust Company, which specialized in small loans to businessmen. In 1911 he established the African Guarantee and Indemnity Company, which handled all types of insurance finance.

Schlesinger first entered the entertainment business in 1913 with the purchase of the Empire Theatre in Johannesburg for £60 000. He rapidly converted a near-bankrupt enterprise into a flourishing concern, African Consolidated Theatres, and provided a centralized organization for the distribution of films and variety acts on a nationwide basis. A,subsequent subsidiary enterprise was African Film Productions, with its weekly African Mirror , considered to be the oldest news-reel in the world. During the twenties it was Schlesinger who sponsored the country’s first chain of radio stations, forming the African Broadcasting Company (1930), from which, in 1936, the South African Broadcasting Corporation evolved as a government undertaking.

Schlesinger also interested himself in commercial farming, and at Langholm, near Grahamstown, he pioneered several large pine-apple plantations, establishing a canning factory in Port Elizabeth. At Kendrew, near Graaff-Reinet, he embarked on an elaborate programme of citrus cultivation under intensive irrigation, a project which failed, however, owing to the technical inadequacies of the catchment area. It was in Zebediela, in the northern Transvaal, that he developed what became the largest single citrus estate in the world.

By the early thirties, on the basis of the spectacular success of the insurance companies he had founded, Schlesinger had come to own an imposing network of cinemas and theatres, besides holding major interests in retail concerns, banking, advertising, hotels, catering, amusement parks, agriculture, canning, diamond cutting and newspapers, besides being chairman of more than eighty companies.