You are browsing the archive for Robben Island.

Island of Tears

November 4, 2009 A married couple who had contracted an unknown skin disease early in the previous century, was banned as “lepers” to Robben Island, where they were separated from their community, their four children and from each other until their death. Faan Pistor, who recently searched in vain for his paternal grandparents’ graves on the island, here tells more about this forgotten heritage.

A married couple who had contracted an unknown skin disease early in the previous century, was banned as “lepers” to Robben Island, where they were separated from their community, their four children and from each other until their death. Faan Pistor, who recently searched in vain for his paternal grandparents’ graves on the island, here tells more about this forgotten heritage.

Nearly ten years after Robben Island was declared a World Heritage Site on 2 December 1999, it is now in Heritage Month (September 2009) appropriate to take a look at a forgotten aspect of the island’s rich and many-sided cultural heritage.

Very few people know that the island was a “leper” colony from 1846 until 1931. But how did patients come to end up on the island?

The answer to this question can be found in the archival sources of the state and a few denominations. There also used to be a Robben Island Society, which was given a building on the island decades ago to use as museum. Former islanders donated photographs and various other items of historical importance, but the museum had been closed down when the jail for political prisoners was established.

In 1996 a society was established once again to help preserve the history and memory of especially the thousands of people who had lived and died on the island when there was a primitive sanatorium for “lepers” and an asylum for “lunatics”. This society was short-lived.

One of the reasons for its founding was to unanimously make proposals on behalf of interested and affected parties to the then Committee on the Future of Robben Island. As a member of the Society I proposed that research be done on who are buried there, tombstones be erected where possible, as well as a joint memorial for those whose graves are unmarked.

One of the reasons for its founding was to unanimously make proposals on behalf of interested and affected parties to the then Committee on the Future of Robben Island. As a member of the Society I proposed that research be done on who are buried there, tombstones be erected where possible, as well as a joint memorial for those whose graves are unmarked.

I also supported keeping the nature reserve on the island, as well as establishing a new island museum to portray all the phases and facets of the island’s history. On a visit on 25 August this year as a guest of Prof. Henry Bredekamp, chief executive of the Iziko Museums and acting chief executive of the Robben Island Museum, my impression was that not enough is being done to preserve and reflect especially the history of the 85 years from 1846 to 1931 and to protect the environment. It struck me that the island had gone downhill in various respects since my previous visit on 8 February 1991.

All that it currently offers tourists, is the prison museum and a struggle-related curio shop.

Serious thought ought now to be given to as to how a visit to the island can be made multifaceted and more satisfactory for visitors. Restoring the memory of all those who had suffered and died on Robben Island is long overdue. In this regard the state has a huge debt of honour to settle.

◊◊◊

My passion for Robben Island is rooted in ties of flesh and blood: My late father, Johan Hendrik Pistor, was born there on 27 December 1909, my grandfather Johan Hendrik Frederik Pistor died there in 1922 and my grandmother Martha Jacoba Maria (born Van der Westhuizen) died there in 1925. They were allegedly leprous and today their graves are unmarked.

Grandpa and Grandma were married in Piketberg on 9 May 1899. Ten years later, when there were already three children in the family, something terrible happened: Grandma was diagnosed with “leprosy”, about which doctors knew very little at that time. She then was 28 years old. She was removed under warrant like a criminal from her husband, children and community. The state stripped her of her human dignity. She was dumped, oppressed, humiliated, neglected, forsaken and forgotten on Robben Island by the state.

Just like the political prisoners decades later, the “lepers” were given numbers by the island authorities. Thus Mrs. M.J.M. Pistor in 1909 became “Leper 604”. Ten years thereafter Grandpa was also banned to the island as a “leper”. Mr. J.H.F. Pistor became “Leper 1717”.

Apart from being separated from all the other people on the island, the “lepers” were also separated according to race and strictly according to sex. In Grandpa’s last three years on earth he and Grandma were not even allowed to live together like legally married people!

Shortly after Father’s birth, mother and child were separated by the state when he, just like his three elder siblings, was compelled to be fostered out. He met his sister and two brothers for the first time when he was already 26 years old. The Cape daily Die Burger on 31 October carried a report about this family meeting. Father kept a clipping of it in his Bible until the day he died in 1989.

◊◊◊

After removing the remaining patients from the island, the state by reason of ignorance and unfounded fears for contamination, on 14 January 1931 burnt down all 90 buildings used by the “lepers”, except the Anglican Church of the Good Shepherd.

The compulsory detention of so-called lepers on Robbend Island was the result of a worldwide leprosy scare. The Cape Parliament passed the Leprosy Repression Act in 1891. Anyone that had been diagnosed with any form or degree of leprosy, had to be removed to the island. Unfortunately people suffering from obvious skin diseases often were regarded as leprous. Therefore many with skin disorders were hidden by their families for fear of the hell on the island.

Family members of people diagnosed with “leprosy” were not easily given jobs. Fear-stricken people diagnosed with “leprosy” often fled before warrants against them could be executed.

The patients did not get the necessary medical treatment on the island. They had to take care of one another. Some of the medical staff members often were rude and cruel towards them. They were also spiritually neglected at times. One dominee regularly failed to visit them. In addition he did not always turn up to conduct burials. So, the “leprous” patients bitterly complained that this state of affairs was “scandalous”, they were “grossly neglected” and “nobody cares about our souls”. Religious gatherings and burials were sometimes conducted by Mr. Guillaume Francois Malan, a Paarl school master who was a “leprous” patient from 1901 until 1929.

“Lepers” sometimes were buried in old blankets instead of coffins. One patient revealed on 29 April 1862 in a letter in the Cape Monitor: “ . . . three were buried yesterday in one grave, two white men and a leper . . . we dare not say anything about it to the authorities here, because if we make complaints it only makes matters worse . . . ”

The state thought so little about the suffering and the memory of the patients that it built a maximum security prison over the graves of thousands of patients, most of whom were black.

With the exception of the piece of land on which the Anglican church was erected, the rest of the island’s 574 ha belongs to the state. Apart from this church, all that have a bearing on the “lepers” and that remained after 1931,

was the women’s tidal pool with its stone wall, and a beautiful garden close to their infirmary. The tidal pool is still there, but polluted and neglected and the stone wall is dilapidated. The garden went to rack and ruin long ago.

There also used to be a separate jetty and entrance for “lepers”. It was not without reason known as the “Gate of Tears”. Many patients cried uncontrollably on arrival.

◊◊◊

Out of the current 890 World Heritage Sites, South Africa is privileged to have the only two that are within sight from each other: Cape Town’s own Table Mountain and Robben Island.

The island is many things for many people. An announcement on the founding of an inclusive, multilingual Robben Island Historical Society and the registration thereof as a full-fledged NGO that would like to cooperate with the state and Unesco is to be expected very soon.

◊ Faan Pistor can be contacted by e-mailed here at or at 021 552 0850.

Walter Sisulu

June 23, 2009A perfect example of the enigmatic genetic whirlpool at the tip of the African continent and the forces that have shaped the country, the birth of Walter Sisulu is one of the most tantalising events of his time.

Born on May 18, 1912 to Alice Mase Sisulu, a relative of Nelson Mandela's first wife, Evelyn Mase, this revered statesmen and symbol of the apartheid struggle, who served 26 years behind bars and on Robben Island for his commitment to freedom, was the product of what was seen as a scandalous union at the time.

Paternal Ancestry.

His mother, who refused to give credence to the unspoken colour and gender barriers before apartheid became official in 1948, left her rural home in Qutubeni, Transkei, to work in white homes and entered into a long-term relationship with a white man, Albert Victor Dickinson. Though no reason is given in the Sisulus' biography ‘In Our Lifetime', Walter's daughter-in-law Elinor says the couple chose not to marry when Walter was born. Four years later the couple had another child, Rosabella.

The boy child was christened Walter Max Ulyate Sisulu at the Anglican All Saints Mission near Qutubeni – a tantalising clue that invites investigation, as the Ulyate family was a well-known 1820 Settler family that farmed in the Eastern Cape.Though he was aware of the existence of his father, who Elinor suggests wanted to adopt him, Dickinson played no role in Walter's upbringing. Walter and Rosabella were raised by his mother's extended Hlakule/Sisulu family, who were descended from the royal Thembu clan that traces its genealogy 20 generations back to King Zwide. All that is known of Albert Victor Dickinson, whom Walter only met a few times, is that he was born on July 9, 1886, and was the son of Albert Edward Dickinson of Port Elizabeth. Elinor says there were conflicting oral reports as to whether he was a road supervisor or a magistrate, but he worked in the Railway Department of the Cape Colony from 1903 to 1909 and was transferred to the Office of the Chief Magistrate in Umtata in 1910.

Walter Sisulu died on May 5, 2003, a week short of his 91st birthday. He is buried in Croesus Cemetery, Newclare, Johannesburg. His wife, Albertina, herself an important icon in the struggle years, lives in Johannesburg.

Article written by: Sharon Marshall

The Sisulu wedding, 1944. (Standing on the left is Nelson Mandela. The pretty bridesmaid next to him is Evelyn Mase, Mandela's future wife.)

(With kind permission from South African History Online.)

Source: SESA (Standard Encyclopedia of Southern Africa)

Eva (Krotoa) van die Kaap

June 9, 2009

Eva (Krotoa) van die Kaap

Krotoa was born at the Cape, circa 1642 – died Cape Town, 29th July 1674. A female Hottentot interpreter, Eva was a member of the Goringhaikona (Strandlopers or Beach-combers), a Hottentot tribe which lived in the vicinity of Table Bay. The captain of this tribe, Herry, was her uncle, and her sister was the wife of Oedasoa, captain of the Cochoqua (Saldanhars).

Shortly after their arrival at the Cape, Jan van Riebeeck and his wife took Eva into their home. They gave her a Western education and instructed her in the Christian religion. She soon learnt to speak Dutch fluently, and, later on, was able to make herself understood in Portuguese. Although she did not receive official payment for this, she was used as an interpreter, especially between V.O.C. officials and Oedasoa, with whom she sometimes went to stay.

Van Riebeeck had a high opinion of her ability as an interpreter, although later he warned his successor not to accept everything she said without reservations.

On the 3rd May 1662, Eva was baptized in the church inside the Fort of Good Hope by a visiting minister, the Rev. Petrus Sibelius, with the secunde, Roelof de Man and the sick comforter, Pieter van der Stael, as witnesses. She was also the first Hottentot to marry according to Western customs.

On the 26th April 1664, and with the permission of the Council of Policy, she was married in a civil ceremony to the explorer, Pieter van Meerhoff, and she received a dowry of fifty rix-dollars from the V.O.C. On the 2nd June 1664 the marriage was also solemnized in church. Of the children born from this marriage three survived.

In May 1665 Van Meerhoff and his family left the Cape when he was sent to Robben Island as commander. In 1667 he was murdered during an expedition to Madagascar and on 30 September 1668 Eva returned to the Cape with her children, where the V.O.C. gave them the old pottery workshop as a home.

She lapsed into such a dissolute and immoral life, however, that the V.O.C. again sent her to Robben Island on 26th March 1669, and placed the three children in the care of the free burgher, Jan Reyniersz. Eva returned to the mainland on various occasions, but was always banished to the island.

In May 1673 she was allowed to have a child baptized on the mainland and, in spite of her outrageous way of living, was buried in the church inside the Castle on the day after her death.

In 1677 the free burgher, Bartholomeus Borns recieved permission from the Council of Policy to take two of Eva’s children, Pieternella (Petronella) and Salamon van Meerhoff, with him to Mauritius. There Pieternella van Meerhoff married Daniel Zaayman (from Vlissingen), and, on 26th January 1709, arrived with her husband at the Cape, where she became an ancestor of the Zaayman family in South Africa. There were eight children born of this marriage, four sons and four daughters, of whom most (or all) were probably born on Mauritius.

The family has descended in the male line from the eldest son, Pieter Zaayman; two sons were baptized in Cape Town on 17 February 1709; two daughters were apparently married at the Cape (to Diodati and Bockelberg). A third daughter, Maria Zaayman, had already arrived at the Cape from Mauritius in 1708 with her husband, Hendrik Abraham de Vries, of Amsterdam (one of the four De Vries ancestors in South Africa) there being with her four children, of whom three boys were baptized simultaneously in Cape Town on 4 November 1708.

A fourth daughter, Eva Zaayman, date of birth unrecorded, was married (apparently at the Cape) first to Hubert Jansz van der Meyden, and later (20 September 1711) at Stellenbosch, to Johannes Smit of Delft. As far as is known no children resulted from these marriages.

Source: SESA (Standard Encyclopedia of Southern Africa)

The Fort of Good Hope

May 29, 2009On 8th April, 1652, Jan van Riebeeck took possession of the “Cape Outpost” in the name of the United East India Company and their most Noble and High Mightinesses the States General of the United Netherlands. He built his “Fort of Good Hope” in Table Valley near the beach and east of the Fresh River that flowed from high up on Table Mountain – more or less along old Heerengracht, now Adderley Street, on a part of the site occupied by the old railway station and a bazaar. This fort, with its walls built of sods, was unsuitable for defence against attacks either from the sea or from the interior. In 1664 there was a renewed threat of a maritime war between the Netherlands and her trade rival, England, and the Company decided to replace the old fort by a new fortification, which would be effective against attack by European enemies.The site for this fortification, the Castle, was selected in August, 1665, by the Commissioner, Isbrand Goske, who decided “after many deliberations that the new royal fortress which the Lords Masters conceive of, will be laid out on a suitable level site about 60 roods (that is, Rhineland roods or about 223 metres) further eastwards from the fort.” Before the end of that month Hendrik Lacus, the surveyor and fiscal, assisted by the engineer, Pieter Dombaer, had measured out the new fortification. This fortification was built in accordance with the principles of the old Netherlands defence system, which had been adopted in the Netherlands Republic and its extra-European settlements since the beginning of the seventeenth century. It was to be a pentagonal fortification with bastions at each corner – the shape it still retains to this day. Each wall or courtine between bastions was to be 150 metres long, and the flank of each bastion was to be at right angles to the adjacent courtine so that the flank of a particular bastion commanded the adjacent walls as well as the flank of the bastion opposite. Under each bastion there was to be a powder magazine, and a 25-metre moat was dug round the Castle.

The actual building of the fort was entrusted to the engineer Pieter Dombaer, who was assisted by the carpenter Adriaan van Braeckel and the master mason Douwe Gerbrandtz Steyn. The vegetation to the east of the fort site was cut down, and foundations three metres wide and three to six metres deep were laid on bedrock.

On 2nd January, 1666, four corner stones were laid with great ceremony by Governor Zacharias Wagenaar and others. Slaves were used to obtain building materials such as stone, lime burnt from shells from Robben Island and timber from Hout Bay, while soldiers did the actual building. When the war came to an end in 1667, two bastions had been completed and the work was stopped. However, hostilities between the Netherlands and England broke out again in 1672, whereupon work on the Fort was immediately resumed. By 1674 the old fort could be evacuated and the Castle was occupied for the first time, although it was not completed until 26th April, 1679.

At this stage the five bastions were named after the titles of the Prince of Orange. The northern bastion, now nearest to the railway lines, was called Buren and contained the quarters of some of the officers and men. On top of the bastion, 12, 18- and 24-pounder cannon were mounted; there were altogether about a hundred such cannon in the Castle during the eighteenth century. Also on Buren was the garden in which Lady Anne Barnard strolled in the days of Lord Macartney (1797- 1798) and just outside, against the wall, there was a toll gate in the time of the Dutch East India Company which everyone coming to Cape Town with produce from the interior had to use.

The eastern bastion is named Katzenellenbogen. Here the tricolour flag was flown, and below it sas the “black hole” and other cells where miscreants were incarcerated.

The south-eastern bastion is Nassau, with its own grouping of store-rooms and offices.

The southern bastion is Oranje. There the guards of the armoury were housed, and it also contained the quarters and workshops of the gunsmiths.

Between the Nassau and the Katzenellenbogen bastions there was a sally port with iron doors. Up to 1682 the entrance to the Castle was situated between the Buren and Katzenellenbogen bastions, that is, facing the sea. Simon van der Stel was instructed to move it to the “Curtain” between Buren and Leerdam, where it is now. The bell-tower above the entrance is made of “klompies”-brieks and the original bell, cast in Amsterdam in 1697, still hangs in it. The pediment above the entrance bears the coat-of-arms of the United Netherlands and on both ends of the architrave below them the coat-of-arms of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Delft, Zeeland, loom and Enkhuizen: towns in which the various Chambers which constituted the Company, were situated. Not only did buildings adjoin the bastions and the walls inside the castle, but, on the instructions of Commissioner van Rheede, a wall (known as the Kat) was built, jutting out from the Katzenellenbogen over the courtyard to a point midway between the Leerdam and the Oranje bastions, together with a gate (above which the old sundial can still be seen) connecting the outer court to the inner court or wapenplaats. Other buildings were soon erected on both sides of the 12 metres high wall. To the right of the gateway was the Governor’s residence and a large council ball, completed in 1695, which was also used as a church until 1704; later it became Lady Anne Barnard’s reception hall and it is now fully restored. The covered stoep of the Governor’s residence with its fluted kiaat pillars, its graceful wrought-iron railings, its staircase rails with brass knobs, its balcony decorations and the carved fanlight above the front door, is a striking example of the joint efforts of the sculptor Anreith and the architect Thibault. Anreith’s workshop in the Castle stood at the junction of the transverse wall and the outer wall between the Leerdam and the Oranje bastions.

To the left of the gateway was the residence of the Secunde, and under it were the grain cellars, which were also built by Simon van der Stel. The outer court contained most of the government offices and also the house of the captain of the military forces. The captain’s tower, from which a watch could be kept on the sea, still stands unchanged between the Leerdam and the Oranje bastions.

The Castle had its own well, which still exists, and in Company times there was a pyramid of cannon balls in every courtyard, conveniently stacked for any eventuality. However, as early as the seventeenth century it was realised that the Castle could not be readily defended against an enemy who, after landing, occupied Devil’s Peak. Consequently many supplementary fortifications were erected along the beach as well as ravelins or couvrefaces outside the walls of the Castle, and forts high up Devil’s Peak.

From 1674 to 1795 the Castle was the headquarters of the government of the Dutch East India Company at the Cape. It was the official residence of the governor, and during the first half of the 19th century the British governors used it for the same purpose. When the British governors went to live permanently in Government House, the Castle continued to serve as the military headquarters and the seat of the government and civil service, but during the 19th century the government departments were gradually removed so that only the military services remained. In 1917 the Imperial Forces handed the Castle over to the Defence Force of the Union by whom it is still used.

There can be no question that the Castle of Good Hope is the oldest and also historically the most interesting building in the country.

Acknowledgments to: The Historical Monuments of South Africa, Heritage Resource Agency

Thomas William Bowler's depiction of The Castle (With kind permission from Iziko Museums)

Robben Island

May 28, 2009

Robben Island

ROBBEN ISLAND (meaning ‘seal island’) is situated in Table Bay, 9,3 km north of Green Point and 7 km west of Bloubergstrand in the Cape magisterial district. It is roughly oval in shape, with the longest axis running north and south. The maximum length is 3,4 km and the maximum breadth little more than 1,8 km, with an area of 5,2 sq km. The island is low-lying but undulating. The highest point (14 metres is on the southern coast and on this mound the lighthouse stands. The coastline is mostly rocky, except for Murray’s Bay, the harbour. The underlying rock is blue slate of the Malmesbury Series, covered over by coastal blown sands, and sands with limestone. The climate is similar to that of Cape Town, with high winds, N.W. in the winter months, S. and S.E. in summer.

Many early navigators visited the island before the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck in 1652. After the discovery of the sea route to the East Indies, outward bound or returning vessels usually called at the Cape for fresh provisions. Some captains, who could not induce the Hottentots on the mainland to part with their livestock, resorted to Robben Island as their major source of fresh supplies in the form of seals, penguins and eggs of various birds. In 1608 Cornelis Matelief relates how his men amused themselves by clubbing hundreds of seals and penguins. Ships rounding the Cape of Good Hope showed their preference for the uninhabited island. Frequently they would leave letters, usually under well-marked rocks. It became a regular practice to leave lean sheep on the island in exchange for fatter ones taken off. The island bore various names given by early mariners, such as Seal, Penguin and Robben. Joris van Spilbergen in 160i named it, in honour of his mother, Isla de Cornelia.

Table Bay once swarmed with whales which used to come to calve, but as more and more ships intruded, the whales gradually abandoned it. In 1611 Jacob le Maire and some sailors were left behind by his father, Isaac le Maire. The party were to club seals on the island for their pelts and train-oil, and to hunt whales for their blubber. In the same year King James I sent convicts to the Cape to establish a settlement; these men later settled on Robben Island until they were returned to England. In March 1636 Hendrik Brouwer, former governor-general of the Dutch East Indies, after an attempt at mutiny aboard one of his ships in Table Bay, banished the ringleaders to Robben Island.

Van Riebeeck upon his first voyage to the island in 1652 realised its potential. During those first uncertain years the colonists were often without food, and the Commander depended on Robben Island’s wild life to feed his people, retaining the few cattle and sheep obtained by barter from the Hottentots for passing vessels of the Dutch East India Company. Van Riebeeck soon proclaimed the wild life on the island to be prohibited game. The uncertainty of trade with the Hottentots compelled him to build up a stock of sheep and other domestic animals on the island. On a April 1654 he introduced rabbits. The pastures soon proved superior to any near the mainland settlement, partly because the mainland was wild and overgrown. The island was not as wet as the mainland and there were no leopards, lions, jackals, baboons or thieving Hottentots. These advantages were exploited to the full.

Later, Van Riebeeck placed a superintendent with a party of men on the island. They were responsible, inter alia, for keeping a look-out for Company’s ships, and if these approached toward dusk, a fire was lit to help guide them toward an anchorage. In July 1657 Van Riebeeck ordered the erection of a permanent beacon on which fires were to be lit every night. This was the first navigational aid on the South African coast. Another important task was the collecting of sea-shells for the lime-kilns. Shiploads were regularly brought to the mainland, and this practice continued long after Van Riebeeck’s time. Hermann Schutte, who built the Groote Kerk and the old Green Point lighthouse, was a stone-dresser on the island and in many of his constructions later used blue slate from Robben Island. The stone was described by a visitor in 2834 as ‘excellent slate coloured stone, that is a little inferior to marble and beautifully veined’.

When the settlement on the mainland was well established, the function of the island changed. It first became a penal settlement. From the Malay Peninsula and Indonesia the Dutch brought political prisoners. The Prince of Ternate was banished to the island after it was discovered that he was running a brothel on the mainland. The Prince of Madura died on Robben island in 1754; his body was returned to his homeland. Today there stands a kramat (Moslem shrine) as a reminder of this period in the island’s history.

During the governorship of Cornelis van Quaelberg (1666-6 small, scattered deposits of gold and silver were found on the island, but it was found to be far from an economic proposition to mine these metals. In 1806 John Murray was granted permission by the British to start a whaling station in the bay and harbour on the island which still bear his name, but in 1820 the authorities closed his enterprise, as the boats were an open invitation for prisoners to escape. The Xhosa prophet Makana – self-styled ‘brother of Christ’, who unsuccessfully led his people against Grahamstown in 1819- was drowned while attempting to escape. In 1833 Capt. Richard Wolfe took over as commandant of the penal settlement, bringing with him the artist Thomas Bowler as tutor to his children. In 1891 Wolfe was responsible for building the village church.

In Dec. 1845 John Montagu, Secretary to the Government, had the lepers removed from Hemel-en-Aarde, beyond Caledon, to Robben Island. The criminals were returned to the mainland to work on the roads. After the Eighth Frontier War (1850-53) Sir George Grey banished the most treacherous of the Xhosa chiefs to the island. Nongquase, after her visions which led to the death of over 70 000 of her people in 1856-57, was placed on the island for her own protection.

More and more of the unwanted members of Cape society were sent to Robben Island. It became the home of lepers, lunatics, law-breakers, the chronic sick and paupers. Their suffering caused many a public outcry, and between 1852 and 1909 about a dozen select committees and numerous commissions were instructed to deal with conditions on the island. The infirmary was condemned and its complete removal to the mainland recommended.

In 1890 the women paupers were removed to Grahamstown, but it was not until 1913 that the removal of lunatic patients and others was begun. The lepers stayed on until they were moved to Pretoria in 1932.Wednesday 14 Jan. 1931 marked the end of the Robben Island infirmary when the leper wards were razed by fire.

The fogs and rough seas experienced off the island are a great handicap. During winter months especially the strong north-westerly gales cause heavy seas. Before the island harbour and lighthouse were built, these seas caused many shipwrecks and great loss of life. The lighthouse was built on Minto Hill in 1864. After the loss of the Tantallon Castle in dense fog in 1905 the authorities added an explosive fog-signal, which was replaced by a more modern fog-horn in 1925. It was estimated that the sound would travel in the thickest fog for a distance of about is kilometres. At the time of installation this fog-horn was reputed to be the second biggest in the world. In 1938 a 216-mm diaphone was added and a radio beacon was installed. A further addition to the light in 1940 was a red arc, showing over the treacherous Whale Rock which lies just off the southern point of the island.

Shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War the Defence Department took over the island to prepare it as a fortress guarding the Cape and Table Bay. A new harbour was built at Murray’s Bay, an air-strip was laid, and two batteries of artillery were assembled on the island. In the 1955 the island was taken over by the South African navy as S.A.S. Robben eiland, but control passed to the Prisons Department in 1965.

The First Burghers at the Cape

May 28, 2009 The preliminary arrangements for releasing some of the Company’s servants from their engagements and helping them to become farmers were at length completed, and on the 21st of February 1657 ground was allotted to the first burghers in South Africa. Before that date individuals had been permitted to make gardens for their own private benefit, but these persons still remained in the Company’s service. They were mostly petty officers with families, who drew money instead of rations, and who could derive a portion of their food from their gardens, as well as make a trifle occasionally by the sale of vegetables. The free burghers, as they were afterwards termed, formed a very different class, as they were subjects, not servants of the Company. For more than a year the workmen as well as the officers had been meditating upon the project, and revolving in their minds whether they would be better off as free men or as servants. At length nine of them determined to make the trial. They formed themselves into two parties, and after selecting ground for occupation, presented themselves before the Council and concluded the final arrangements. There were present that day at the Council table in the Commander’s hall, Mr Van Riebeek, Sergeant Jan van Harwarden, and the Bookkeeper Roelof de Man. The proceedings were taken down at great length by the Secretary Caspar van Weede.

The preliminary arrangements for releasing some of the Company’s servants from their engagements and helping them to become farmers were at length completed, and on the 21st of February 1657 ground was allotted to the first burghers in South Africa. Before that date individuals had been permitted to make gardens for their own private benefit, but these persons still remained in the Company’s service. They were mostly petty officers with families, who drew money instead of rations, and who could derive a portion of their food from their gardens, as well as make a trifle occasionally by the sale of vegetables. The free burghers, as they were afterwards termed, formed a very different class, as they were subjects, not servants of the Company. For more than a year the workmen as well as the officers had been meditating upon the project, and revolving in their minds whether they would be better off as free men or as servants. At length nine of them determined to make the trial. They formed themselves into two parties, and after selecting ground for occupation, presented themselves before the Council and concluded the final arrangements. There were present that day at the Council table in the Commander’s hall, Mr Van Riebeek, Sergeant Jan van Harwarden, and the Bookkeeper Roelof de Man. The proceedings were taken down at great length by the Secretary Caspar van Weede.

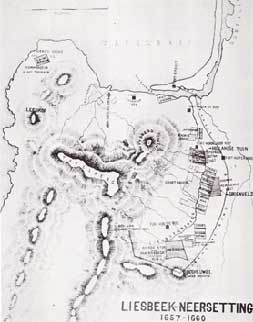

The first party consisted of five men, named Herman Remajenne, Jan de Wacht, Jan van Passel, Warnar Cornelissen, and Roelof Janssen. They had selected a tract of land just beyond Liesbeek, and had given to it the name of Groeneveld, or the Green Country. There they intended to apply themselves chiefly to the cultivation of wheat. And as Remajenne was the principal person among them, they called themselves Herman’s Colony. The second party was composed of four men, named Stephen Botma, Hendrik Elbrechts, Otto Janssen, and Jacob Cornelissen. The ground of their selection was on this side of the Liesbeek, and they had given it the name of Hollandsche Thuin, or the Dutch Garden. They stated that it was their intention to cultivate tobacco as well as grain. Henceforth this party was known as Stephen’s Colony. Both companies were desirous of growing vegetables and of breeding cattle, pigs, and poultry.

The conditions under which these men were released from the Company’s service were as follows :

They were to have in full possession all the ground which they could bring under cultivation within three years, during which time they were to be free of taxes. After the expiration of three years they were to pay a reasonable land tax. They were then to be at liberty to sell, lease, or otherwise alienate their ground, but not without first communicating with the Commander or his representative. Such provisions as they should require out of the magazine were to be supplied to them at the same price as to the Company’s married servants. They were to be at liberty to catch as much fish in the rivers as they should require for their own consumption.

They were to be at liberty to sell freely to the crews of ships any vegetables which the Company might not require for the garrison, but they were not to go on board ships until three days after arrival, and were not to bring any strong drink on shore. Called Stephen Janssen, that is Stephen the son of John, in the records of the time. More than twenty years later he first appears as Stephen Botma. From him sprang the present large South African family of that name.

They were not to keep taps, but were to devote themselves to the cultivation of the ground and the rearing of cattle. They were not to purchase horned cattle, sheep, or anything else from the natives, under penalty of forfeiture of all their possessions.

They were to purchase such cattle as they needed from the Company, at the rate of twenty-five gulden for an ox or cow and three gulden for a sheep.

They were to sell cattle only to the Company, but all they offered were to be taken at the above prices.

They were to pay to the Company for pasturage one tenth of all the cattle reared, but under this clause no pigs or poultry were to be claimed.

The Company was to furnish them upon credit, at cost price in the Fatherland, with all such implements as were necessary to carry on their work, with food, and with guns, powder, and lead for their defence. In payment they were to deliver the produce of their ground, and the Company was to hold a mortgage upon all their possessions.

They were to be subject to such laws as were in force in the Fatherland and in India, and to such as should thereafter be made for the service of the Company and the welfare of the community. These regulations could be altered or amended at will by the Supreme Authorities. The two parties immediately took possession of their ground and commenced to build themselves houses.

They had very little more than two months to spare before the rainy season would set in, but that was sufficient time to run up sod walls and cover them with roofs of thatch. The forests from which timber was obtained were at no great distance; and all the other materials needed were close at hand. And so they were under shelter and ready to turn over the ground when the first rains of the season fell. There was a scarcity of farming implements at first, but that was soon remedied.

On the 17th of March a ship arrived from home, having on board an officer of high rank, named Ryklof van Goens, who was afterwards Governor General of Netherlands India, He had been instructed to rectify anything that he might find amiss here, and he thought the conditions under which the burghers held their ground could be improved. He therefore made several alterations in them, and also inserted some fresh clauses, the most important of which are as follows:

1. The freemen were to have plots of land along the Liesbeek, in size forty roods by two hundred – equal to 133 morgen – free of fixes for twelve years.

2. All farming utensils were to be repaired free of charge for three years. In order to procure a good stock of breeding cattle, the free-men were to be at liberty to purchase from the natives, until further instructions should be received, but they were not to pay more than the Company.

3. The price of horned cattle between the freemen and the Company was reduced from twenty-five to twelve gulden.

The penalty to be paid by a burgher for selling cattle except to the Company was fixed at twenty rix-dollars.

4. That they might direct their attention chiefly to the cultivation of grain, the freemen were not to plant tobacco or even more vegetables than were needed for their own consumption.

5. The burghers were to keep guard by turns in any redoubts which should be built for their protection.

6. They were not to shoot any wild animals except such as were noxious. To promote the destruction of ravenous animals the premiums were increased, viz, for a lion, to twenty-five gulden, for a hyena, to twenty gulden, and for a leopard, to ten gulden.

7. None but married men of good character and of Dutch or German birth were to have ground allotted to them. Upon their request, their wives and children were to be sent to them from Europe. In every case they were to agree to remain twenty years in South Africa.

8. Unmarried men could be released from service to work as mechanics, or if they were specially adapted for any useful employment, or if they would engage themselves for a term of years to the holders of ground.

9. One of the most respectable burghers was to have a seat and a vote in the Council of Justice whenever cases affecting freemen or their interests were being tried. He was to hold the office of Burgher Councillor for a year, when another should be selected and have the honour transferred to him.

To this office Stephen Botma was appointed for the first term. The Commissioner drew up lengthy instructions for the guidance of the Cape government, in which the Commander was directed to encourage and assist the burghers, as they would relieve the Company of the payment of a large amount of wages. There were then exactly one hundred persons in South Africa in receipt of wages, and as soon as the farmers were sufficiently numerous, this number was to be reduced to seventy.

Many of the restrictions under which the Company’s servants became South African burghers were vexatious, and would be deemed intolerable at the present day. But in 1657 men heard very little of individual rights or of unrestricted trade. They were accustomed to the interference of the government in almost every thing, and as to free trade, it was simply impossible. The Netherlands could only carry on commerce with the East by means of a powerful Company, able to conduct expensive wars and maintain great fleets without drawing upon the resources of the State. Individual interests were therefore lost sight of even at home, much more so in such a settlement as that at the Cape, which was called into existence by the Company solely and entirely for its own benefit.

A commencement having been made, there were a good many applications for free papers. Most of those to whom they were granted afterwards re-entered the Company’s service, or went back to the Fatherland. The names of some who remained in South Africa have died out, but others have numerous descendants in this country at the present day. There are even instances in which the same Christian name has been transmitted from father to son in unbroken succession. In addition to those already mentioned, the following individuals received free papers within the next twelvemonth : Wouter Mostert, who was for many years one of the leading men in the settlement. He had been a miller in the Fatherland, and followed the same occupation here after becoming a free burgher. The Company had imported a corn mill to be worked by horses, but after a short time it was decided to make use of the water of the fresh river as a motive power. Mostert contracted to build the new mill, and when it was in working order he took charge of it on. shares of the payments made for grinding. Hendrik Boom, the gardener, whose name has already been frequently mentioned.

Caspar Brinkman, Pieter Visagie, Hans Faesbenger, Jacob Cloete, Jan Reyniers, Jacob Theunissen, Jan Rietvelt, Otto van Vrede, and Simon Janssen, who had land assigned to them as farmers. Herman Ernst, Cornelis Claassen, Thomas Robertson (an Englishman), Isaac Manget, Klaas Frederiksen, Klaas Schriever, and Hendrik Fransen, who took service with farmers.

Christian Janssen and Peter Cornelissen, who received free papers because they had been expert hunters in the Company’s service. It was arranged that they should continue to follow that employment, in which they were granted a monopoly, and prices were fixed at which they were to sell all kinds of game they were also privileged to keep a tap for the sale of strong drink.

Leendert Cornelissen, a ship’s carpenter, who received a grant of a strip of forest at the foot of the mountain. His object was to cut timber for sale, for all kinds of which pries were fixed by the Council.

Elbert Dirksen and Hendrik van Surwerden, who were to get living as tailor.

Jan Vetteman, the surgeon of the fort. He arranged for a monopoly of practice in his profession and for various other privileges.

Roelof Zieuwerts, who was to get his living as a waggon and plough maker, and to whom a small piece of forest was granted.

Martin Vlockaart, Pieter Jacobs, and Jan Adriansen, who were to maintain themselves as fishermen.

Pieter Kley, Dirk Vreem, and Pieter Heynse, who were to saw yellow wood planks for sale, as well as to work at their occupation as carpenters’.

Hendrik Schaik, Willem Petersen, Dirk Rinkes, Michiel van Swel, Dirk Noteboom, Frans Gerritsen, and Jan Zacharias, who are mentioned merely as having become free burghers. Besides the regulations concerning the burghers, the Commissioner Van Goons drew up copious instructions on general subjects for the guidance of the government. He prohibited the ompany’s servants from cultivating larger gardens than required or their own use, but he excepted the Commander, to whom he granted the whole of the ground at Green Point as a private farm. As a rule, the crews of foreign ships were not to be provided with vegetables or meat, but were to be permitted to take in water freely. The Commander was left some discretion in dealing with hem, but the tenor of the instructions was that they were not to be, encouraged to visit Table Bay.

Regarding the natives, they were to be treated kindly, so as to obtain their goodwill. If any of them assaulted or robbed a burgher, those suspected should be seized and placed upon Robben Island until they made known the offenders, when they should be released and the guilty persons be banished to the island for two or three years. If any of them committed murder, the criminal should be put to death, but the Commander should endeavour have the execution performed by the natives themselves. Caution was to be observed that no foreign language should continue to be spoken by any slaves who might hereafter be brought into the country. Equal care was to be taken that no other weights or measures than those in use in the Fatherland should be introduced. The measure of length was laid down as twelve Rhynland inches to the foot, twelve-feet to the rood, and two thousand roods to the mile, so that fifteen miles would be equal to a degree of latitude. In measuring land, six hundred square roods were to make a morgen. The land measure thus introduced is used in the Cape Colony to the present day. In calculating with it, it must be remembered that one thousand Rhynland feet are equal to one thousand and thirty-three British Imperial feet. The office of Secunde, now for a long time vacant, was filled by the promotion of the bookkeeper Roelof de Man. Caspar van Weede was sent to Batavia, and the clerk Abraham Gabbema was appointed Secretary of the Council in his stead. In April 1657, when these instructions were issued, the European population consisted of one hundred and thirty-four individuals, Company’s servants and burghers, men, women, and children all told. There were at the Cape three male and eight female slaves.

Commissioner Van Goens permitted the burghers to purchase cattle from the natives, provided they gave in exchange no more than the Company was offering. A few weeks after he left South Africa, three of the farmers turned this license to account, by equipping themselves and going upon a trading journey inland. Travelling in an easterly direction, they soon reached a district in which five or six hundred Hottentots were found, by whom they were received in a friendly manner. The Europeans could not sleep in the huts on account of vermin and filth, neither could they pass the night without some shelter, as lions and other wild animals were numerous in that part of the country. The Hottentots came to their assistance by collecting a great quantity of thorn bushes, with which they formed a high circular hedge, inside of which the strangers slept in safety. Being already well supplied with copper, the residents were not disposed to part with cattle, and the burghers were obliged to return with only two oxen and three sheep. They understood the natives to say that the district in which they were living was the choicest portion of the whole country, for which reason they gave it the name of Hottentots Holland.

For many months none of the pastoral Hottentots had been at the fort, when one day in July Harry presented himself before the Commander. He had come, he said, to ask where they could let their cattle graze, as they observed that the Europeans were cultivating the ground along the Liesbeek. Mr Van Riebeek replied that they had better remain where they were, which was at distance of eight or ten hours’ journey on foot from the fort. Harry informed him that it was not their custom to remain long in one place, and that if they were deprived of a retreat here they would soon be ruined by their enemies. The Commander then rated that they might come and live behind the mountains, along by Hout Bay, or on the slope of the Lion’s Head, if they would trade with him. But to this Harry would not consent, as he said they lived upon the produce of their cattle. The native difficulty had already become what it has been ever since, the most important question for solution in South Africa. Mr Van Riebeek was continually devising some scheme for its settlement, and a large portion of his dispatches has reference to the subject. At this time his favourite plan was to build a chain of redoubts across the isthmus and to connect them with a wall.

A large party of the Kaapmans was then to be enticed within the line, with their families and cattle, and when once on this side none but men were ever to be allowed to go beyond it again. They were to be compelled to sell their cattle, but were to be provided with goods so that the men could purchase more, and they were to be allowed a fair profit on trading transactions. The women and children were to be kept as guarantees for the return of the men. In this manner, the Commander thought, a good supply of cattle could be secured, and all difficulties with the natives be removed.

During the five years of their residence at the Cape, the Europeans had acquired some knowledge of the condition of the natives. They had ascertained that all the little clans in the neighbourhood, whether Goringhaikonas, Gorachouquas, or Goringhaiquas, were members of one tribe, of which Gogosoa was the principal chief. The clans were often at war, as the Goringhaikonas and the Goringhaiquas in 1652, but they showed a common front against the next tribe or great division of people whose chiefs owned relationship to each other. The wars between the clans usually seemed to be mere forays with a view of getting possession ‘of women and cattle, while between the tribes hostilities were often waged with great bitterness. Of the inland tribes, Mr Van Riebeek knew nothing more than a few names. Clans calling themselves the Chariguriqua, the Cochoqua, and the Chainouqua had been to the fort, and from the last of these one hundred and thirty head of cattle had recently been purchased, but as yet their position with regard to others was not made out. The predatory habits of the Bushmen were well known, as also that they were enemies of every one else, but it was supposed that they were merely another Hottentot clan. Some stories which Eva told greatly interested the Commander.

After the return of the beach rangers to Table Valley, she had gone back to live in Mr Van Riebeek’s house, and was now at the age of fifteen or sixteen years able to speak Dutch fluently.

The ordinary interpreter, Doman with the honest face, was so attached to the Europeans that he had gone to Batavia with Commissioner Van Goens, and Eva was now employed in his stead. She told the Commander that the Namaquas were a people living in the interior, who had white skins and long hair, that they wore clothing and made their black slaves cultivate the ground, and that they built stone houses and had religious services just the same as the Netherlanders. There were others, she said, who had gold and precious stones in abundance, and a Hottentot who brought some cattle for sale corroborated her statement and asserted that he was familiar with everything of the kind that was exhibited to him except a diamond. He stated that one of his wives had been brought up in the house of a great lord named Chobona, and that she was in possession of abundance of gold ornaments and jewels. Mr Van Riebeek invited him pressingly to return at once and bring her to the fort, but he replied that being accustomed to sit at home and be waited upon by numerous servants, she would be unable to travel so far. An offer to send a wagon for her was rejected on the ground that the sight of Europeans would frighten her to death.

All that could be obtained from this ingenious storyteller was a promise to bring his wife to the fort on some future occasion. After this the Commander was more than ever anxious to have the interior of the country explored, to open up a road to the capital city of Monomotapa and the river Spirite Sancto, where gold was certainly to be found, to make the acquaintance of Chobona and the Namaquas, and to induce the people of Benguela to bring the products of their country to the fort Good Hope for sale. The Commissioner Van Goons saw very little difficulty in the way of accomplishing these designs, and instructed Mr Van Riebeek to use all reasonable exertion to carry them out. The immediate object of the next party which left the fort to penetrate the interior was, however, to procure cattle rather than find Ophir or Monomotapa.

A large fleet was expected, and the Commander was anxious to have a good herd of oxen in readiness to refresh the crews. The party, which left on the 19th of October, consisted of seven servants of the Company, eight freemen, and four Hottentots. They took pack oxen to carry provisions and the usual articles of merchandise. Abraham Gabbema, Fiscal and Secretary of the Council, was the leader. They shaped their course at first towards a mountain which was visible from the Cape, and which, on account of its having a buttress surmounted by a dome resembling a flat nightcap such as was then in common use, had already received the name of Klapmuts. Passing round this mountain and over the low watershed beyond, they proceeded onward until they came to a stream running in a northerly direction along the base of a seemingly impassable chain of mountains, for this reason they gave it the name of the Great Berg River. its waters they found barbels, and by some means they managed to catch as many as they needed to refresh themselves. They were now in one of the fairest of all South African To the west lay a long isolated mountain, its face covered with verdure and here and there furrowed by little streamlets which ran down to the river below. Its top was crowned with domes of bare grey granite, and as the rising sun poured a flood of light upon them, they sparkled like gigantic gems, so that the travellers named them the Paarl and the Diamant. In the evening when the valley lay in deepening shadow, the range on the east was lit up with tints more charming than pen or pencil can describe, for nowhere is the glow of light upon rock more varied or more beautiful. Between the mountains the surface of the ground was dotted over with trees,” and in the month of October it was carpetted with grass and flowers.

Wild animals shared with man the possession of this lovely domain. In the river great numbers of hippopotami were seen ; on the mountain sides herds of zebras were browsing ; and trampling down the grass, which in places was so tall that Gabbema described it as fit to make hay of, were many rhinoceroses.

There is great confusion of names in the early records whenever native clans are spoken of. Sometimes it is stated that Gogosoa’s people called themselves the Goringhaiqua or Goriughaina, at other times the same clan is called the Goringhaikona. Harry’s people were sometimes termed the Watermans, sometimes the Strandloopers (beach rangers). The Bushmen were at first called Visman by Mr Van Riebeek, but he soon adopted the word Sonqua, which he spelt in various ways. This is evidently a form of the Hottentot name for these people, as may be seen from the following words, which are used by a Hottentot clan at the present day :-Nominative singular, sap, a bushman; dual, sakara, two bushmen; plural, sakoa, more than two bushmen. Nominative singular, sas, a bushwoman ; dual, sasara, two bushwomen ; plural, sadi, more than two bushwomen. Common plural, sang, bushmen and bushwomen. When the tribes became better known the titles given in the text were used.

There were little kraals of Hottentots all along the Berg River, but the people were not disposed to barter away their cattle. Gabbema and his party moved about among them for more than a week, but only succeeded in obtaining ten oxen and forty-one sheep, with which they returned to the fort. And so, gradually, geographical knowledge was being gained, and Monomotapa and the veritable Ophir where Solomon got his gold were moved further backward on the charts. During the year 1657 several public works of importance were undertaken.

A platform was erected upon the highest point of Robben Island, upon which a fire was kept up at night whenever ships belonging to the Company were seen off the port. At the Company’s farm at Rondebosch the erection of a magazine for grain was commenced, in size one hundred and eight by forty feet. This building, afterwards known as the Groote Schuur, was of very substantial construction. In Table Valley the lower course of the fresh river was altered. In its ancient channel it was apt to damage the gardens in winter by overflowing its banks. A new and broader channel was therefore cut, so that it should enter the sea some distance to the south-east of the fort. The old channel was turned into a canal, and sluices were made in order that the moat might still be filled at pleasure.

In February 1658 it was resolved to send another trading party inland, as the stock of cattle was insufficient to meet the wants of the fleets shortly expected. Of late there had been an unusual demand for meat. The Arnhem, and Slot van Honingen, two large East Indiamen, had put into Table Bay in the utmost distress, and in a short time their crews had consumed forty head of horned cattle and fifty sheep. This expedition was larger and better equipped than any yet seat from the fort Good Hope. The leader was Sergeant Jan van Harwarden, and under him were fifteen Europeans and two Hottentots, with six pack oxen to carry provisions and the usual articles of barter. The Land Surveyor Pieter Potter accompanied party for the purpose of observing the features of the country, so that a correct map could be made.

To him was also entrusted the task of keeping the journal of the expedition. The Sergeant instructed to learn all that he could concerning the tribes, to ascertain if ivory, ostrich feathers, musk, civet, gold, and precious stones, were obtainable, and, if so, to look out for a suitable place the establishment of a trading station. The party passed the Paarl mountain on their right, and crossing the Berg River beyond, proceeded in a northerly direction until they reached the great wall which bounds the coast belt of South Africa. In searching along it for a passage to the interior, they discovered a stream which came foaming down through an enormous cleft in the mountain, but they could not make their way along it, as the sides of the ravine appeared to rise in almost perpendicular precipices. It was the Little Berg River, and through the winding gorge the railway to the interior passes today, but when in 1658 Europeans first looked into its deep recesses it seemed to defy an entrance.

The travellers kept. on their course along the great barrier, but no pathway opened to the regions beyond. Then dysentery attacked some of them, probably brought on by fatigue, and they were compelled to retrace their steps. Near the Little Berg River they halted and formed a temporary camp, while the Surveyor Potter with three Netherlanders and the two Hottentots attempted to cross the range. It may have been at the very spot known a hundred years later as the Roodezand Pass, and at any rate it was not far from it, that Potter and his little band toiled wearily up the heights, and were rewarded by being the first of Christian blood to look down into the secluded dell now called the Tulbagh Basin.

Standing on the summit of the range, their view extended away for an immense distance along the valley of the Breede River, but it was a desolate scene that met their gaze. Under the glowing sun the ground lay bare of verdure, and in all that wide expanse which today is dotted thickly with cornfields and groves and homesteads, there was then no sign of human It was only necessary to run the eye over it to be assured that the expedition was a failure in that direction. And so they returned to their companions and resumed the homeward march.

Source: Chronicles of the Cape Commanders by George McCall Theal – 1882

Nurses of Robben Island

May 28, 2009

In the early nineteenth century nursing all over the world was considered no better work than that of a servant. The nurses scrubbed floors, washed walls and cleaned toilets, assuming the hospital was modem enough to have toilets. Nurses were not trained. They were usually from the bottom rung of society, poor uneducated women, no better than their sisters who walked the streets. In 1859 the matron of the famous Guy's Hospital in London recorded that in one ward she dismissed three out of four nurses and in another ward one was so drunk she was unable to perform her duties.' Florence Nightingale (1820-1910) changed all this during the Crimean War, when she organised the nursing of the soldiers with such care, love and devotion to duty that they called her "THE LADY WITH THE LAMP". She would, for the rest of her life, throw light on the subject of how to nurse; of how to relieve the sufferings of the sick. No longer were nurses recruited from the ranks of the lowly, but from the middle class of society. Nursing became fashionable and many women gave up the idea of marriage to offer their services to such a worthy cause. More and more trained nurses reached the shores of the Cape Colony and helped with the training of the local women. One such group was the Anglican Sisterhood which arrived in South Africa in 1891.

"]![Nurses of the Mental Institution for Women with Dr E. Moon, Senior Medical Officer (from left), Mr.A de Villiers Brunt, Commissioner and Rev. E. Matson)]](https://ancestry24.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2009/05/robben_island_nurses1.jpg)

Today South Africa can be proud of a nursing profession of the highest order, which could not have been attained were it not for first-class training and responsible young women.

Miss Robinson, a Robben Island matron in charge of lunatics, was so well thought of that the authorities in Bloemfontein, with permission from the Cape Government, asked her, instead of a doctor, to re-organise the lunatic asylum there. It is fitting to reproduce the letter she received when the job was done:

Landdrost Office,

Bloemfontein, 26th May, 1894.

During the early part of this century the nurses on Robben Island trained on duty, either under the direct supervision of the Medical Superintendent or a skilled matron. A leper colony and lunatic asylum held very little attraction for a young blossoming girl. A very special breed of young woman was required; one who had pluck, determination and was not a mere creature of routine practice. She had to play many roles including those of mother, daughter, diplomat and above all an ever smiling young nurse. These combinations were rare, but Lily Ellen Webber was such a girl.

Lily was 17 years old when she left her parents' home in the Channel Islands and boarded the S.S. Gorka bound for Cape Town. She was suffering from a chest ailment and the family doctor suggested to her parents that she be sent to a warmer climate. South Africa was the ideal place. Lily's mother's sister was married to a Government employee on Robben Island and she would not be alone in a strange country.

During the last night of their 25th day at sea a fellow passenger pointed out to Lily Table Mountain which loomed on the horizon. The sight of the Mountain captured the imagination of all the passengers, as it always does, for it meant that they would soon reach "the fairest Cape in all the world". Lily and the other passengers returned to their cabins after the sun had set to complete their packing for in the morning they would anchor in Table Bay. Lily was too excited for sound sleep that night and rose with the dawn when the ship had stopped. Like an eager child reaching for a gift, she jumped to the port-hole to greet the day but when she looked out, all that greeted her was a grey mist, with rain and more rain and it flashed through her mind that with no mountain and no sunshine at journey's end, was this the sunny South Africa she had heard and read so much about? When she finally reached the deck the rain had not abated and the other passengers had already begun to disembark. She patiently waited her turn to enter the basket which would lower her to the waiting tug which would take them to the shore. On the mainland Lily met her uncle and aunt who had come especially from Robben Island in a hired launch to welcome her. Temporarily the rain and mud were forgotten, but soon they made their uncomfortable presence more apparent. Lily's trunk hoisted ashore from the tug, came down with such a thump that the pressure of the luggage on top of it forced the trunk to burst open, scattering all her worldly possessions in the mud and slush. Frantically the customs officers helped to collect all her goods. They replaced them in the damaged trunk and passed her on without further examination. Lily bit her lip. It was too early for her to cry, she had just arrived. What would her aunt and uncle think of her? "I will never forget that day in September 1902", said Lily. "I wanted to cry, but everybody was so kind."

The rain continued for more than a week and they took boarding in Long Street to await better weather. The steamer in the service to Robben Island was too small a craft to brave rough weather. However, it was decided to show Lily the sights of Cape Town, rain or no rain. When finally the rain did stop they received a message from the commander of the S.S. Magnet, Captain Olsen, that he would attempt the journey across to the island, seeing that the weather had much improved. They boarded the vessel at the wooden jetty near the clock tower in Victoria Basin. Both sexes had to jump from the jetty onto the ship, which was especially difficult for the women with their long dresses.

Lily took a particular interest in the passengers to the island as they would be her future colleagues. There was Dr. Jane Waterston and Dr. Murray, medical inspectors of Robben Island, who would return that same day to the mainland. Jack Keet was returning from the Boer War in which he had served with the Robben Island Medical Regiment. He was a very active member of the Robben Island community, who was known for his pleasant personality. He was later nicknamed "Skipper" Jack Keet. The Island Commissioner, George Piers, grandson of Captain Richard Wolfe, former Superintendent of Robben Island 1833-1845, was on board having been absent from the island for a number of months, sitting in judgement of Boer rebels.

The draft of the S.S. Magnet was too deep for her to tie up at the Robben Island jetty. So on arrival she would anchor out to sea. The custom was that the officials were first taken from the steamer to the jetty by rowing boat. The other passengers and cargo were then taken to the jetty by a longboat manned by convicts. A tow-line was brought to the S.S. Magnet from the jetty and, hand-over-hand, the convicts would pull the boat with passengers and cargo towards the jetty. This was a tedious and haphazard procedure and in rough seas many near fatal accidents occurred. Passengers would slip while boarding from the S.S. Magnet to fall into the sea between the longboat and the steamer. Were it not for the swift action of the convicts whose strong arms pulled them out, they would be crushed to death. Once a man fell into the sea and was so quickly pulled to safety by a convict that he still had his pipe in his mouth and his hat on. A woman present fainted.

Lily's first room in the nurses' quarters was small indeed. It contained an iron bedstead, one wooden chair, a chest of drawers and the floors were bare and unstained. After her first working day she decided to resign. This was not for her. To return after a hard day's work to a lonely, bare, cold room and then have to cook her own rations' was too much. Soon after her arrival she received her next big shock with the news of the death of both her family's parents. Her aunt and uncle on the island would return to England. She remembers, "I felt so rejected and alone that, if it were not for the encouragement of Dr. Benjamin and the others, I would not have remained a leper nurse".

Nurses were paid in those days between £4 and £5 a month with a small food allowance. Their duties were multiple and varied between bandaging the wounds of the lepers for hours on end, to cleaning the wards and hourly recording the condition of patients. One day a nurse in the leper asylum entered a cell of a patient alone, which was against the rules. There always had to be at least two when entering a lunatic's cell. This particular patient had cause to dislike nurse intensely and the moment she was within her reach she grabbed her and about to stab her when Lily came round the corner. She grabbed the nurse's lo hair and, just in time pulled her out of the patient's reach. Then Lily removed the heavy bunch of keys from around her slim waist and threatened the patient with them. She gave up her knife. The nurse was most fortunate that she was not wearing a wig!

Many islanders will remember the local midwife Mrs. Chase

Lily, with encouragement, and by her own pluck and determination was to render a loving service to the sick and deformed – the outcasts on the island. In 1908 she, too, was to find happiness. She married the engineer on the island, Charles Ernest Witt, who came from Germany. They raised two daughters and lived a happy contented life on Robben Island until the infirmary was closed in 1931.

During the year 1899 lectures were given to the staff by Dr. Black and Nurse Soutar. That same year the Head Attendant, Mr. Nutt, fractured his thigh, in a struggle with a European patient. The Nutt family on the island and mainland could be considered pioneers in the nursing profession in South Africa. Dr. Black records, "Mr. Nutt, the head attendant, had, I am glad to say, almost entirely recovered from the severe injury he sustained when attacked by a patient. He had performed his duties in a most praiseworthy and conscientious manner, and so has the matron, Mrs. Reid."

There were too many nurses on the island to name each and every one, but they all did their duty in a most praiseworthy manner. In 1900 when small-pox made its appearance on the island they performed extra duties into the late hours of the night, having worked a full day shift. They did this without a murmur.

Acknowledgements:

Simon A. De Villiers – Author if Robben Island, Out of Reach, Out of Mind – A History of Robben Island.

REFERENCES

1. Longmate, Norman. Alive and Well, p. 54.

2. Searle, Charlotte. The History of the Development of Nursing in South Africa 1652-1960, p. 75. C. Struik, Cape Town, 1965.

3. The Cape of Good Hope, Report on the General Infirmary, Robben Island, for the year 1894, p. 128.

4. Private letters of Lily Ellen Webber, married Witt, in the possession of her daughter, Miss Elsa Witt.

5. The Cape of Good Hope, Report on the General Infirmary, Robben Island, for the year 1899, p. 91.

6. Ibid., 1900, p. 113.

What is Leprosy?

An infectious disease, known since Biblical times, which is characterized by disfiguring skin lesions, peripheral nerve damage, and progressive debilitation. Alternative names :Hansen's disease.

Causes, incidence, and risk factors

Leprosy is caused by the organism Mycobacterium leprae. It is a difficult disease to transmit and has a long incubation period, which makes it difficult to determine where or when the disease was contracted. Children are more susceptible than adults to contracting the disease.

Leprosy has two common forms, tuberculoid and lepromatous, and these have been further subdivided. Both forms produce lesions on the skin, but the lepromatous form is most severe, producing large disfiguring nodules. All forms of the disease eventually cause peripheral neurological damage (nerve damage in the extremities) manifested by sensory loss in the skin and weakness of the muscles. People with long-term leprosy may lose the use of their hands or feet due to repeated injury which results from absent sensation.

Leprosy is common in many countries in the world, and in temperate, tropical, and subtropical climates. Effective medications exist, and isolation of victims in "leper colonies" is unnecessary.

The emergence of drug-resistant Mycobacterium leprae, as well as increased numbers of cases worldwide, have led to global concern about this disease.

Prevention

Prevention consists of avoiding close physical contact with untreated people. People on long-term medication become noninfectious (they do not transmit the organism that causes the disease).

Symptoms

exposure or family members with leprosy, living or visiting areas of the world where leprosy is endemic (cases are known to occur in that area)

Symptoms include:

One or more hypopigmented skin lesions that have decreased sensation to touch, heat, or pain. Skin lesions that do not heal after several weeks to months. Numbness or absent sensation in the hands and arms, or feet and legs. Muscle weakness resulting in signs such as foot drop (the toe drags when the foot is lifted to take a step)

Signs and tests

Lepromin skin test can be used to distinguish lepromatous from tuberculoid leprosy, but is not used for diagnosis. Skin scraping examination for acid fast bacteria (typical appearance of Mycobacterium leprae).

Military Chaplains

May 25, 2009

One of the consequences of the deeply felt need for preparation and strength through faith has been the appointment in the army of men able to give spiritual support. Clergymen were on board the ships of Bartholomew Dias (1488), Vasco da Gama (1497) and the Dutch merchant ships which were in operation before the formation of the Dutch East India Company, in the form of parsons and sick-comforters, that they might provide spiritual comfort and ministration to those on board and at trading posts.

In 1652 Willem Barentsz Wylant ministered as the first sick-comforter at the Cape. In 1665 the Rev. Johannes van Arckel made his appearance as the first minister to be settled at the Cape, where he and his successors also ministered to members of the garrison.

With the First British Occupation (1795-1803) the first Anglican military chaplain, fleet chaplain J. E. Attwood, arrived at the Cape in 1795. He was succeeded by four army and navy chaplains who held divine service in the Castle and cared for the spiritual needs of the British military. During the Batavian period (1803-1806) the military were ministered to as part of the local parish. The spiritual needs of Roman Catholic soldiers were taken care of by three priests brought to the Cape.

During 1806-1814, under the Second British Occupation, there once again appeared at the Cape Anglican military chaplains who were responsible also for the erection of church buildings in Simonstown (1814), Wynberg (1821) and Cape Town (1834). During the Sixth Frontier War (1834-35) military chaplains accompanied the British troops. At the request of the governor, Sir Harry Smith, three military chaplains were sent to British Kaffraria (1848), Natal (1848) and King William’s Town (1850). British military chaplains made their appearance in Natal in 1843, in the Orange River Sovereignty in 1848, and with the British troops in Pretoria in 1877.

Both during the war of 1880-81 as well as during the Second Anglo Boer War military chaplains of various denominations accompanied the British troops. At the time of the Second British Occupation of the Cape and for some time after that the Anglican Church and the Dutch Reformed Church were the only two officially recognised religious denominations. Lay preachers of British origin, such as the Methodist Ireland John Irwin and Sergeant Kendrick – followed later by recognised British military chaplains – gave spiritual care to members of their faith in the military forces at the Cape and later elsewhere in South Africa.

In 1812 the Rev. G. Thom was appointed as the first part-time military chaplain to the Presbyterians among the British troops. During the Second Anglo-Boer War other denominations such as the Roman Catholic and Baptist Churches permitted their chaplains to take part in the campaign. The spiritual care of British troops by British military chaplains in South Africa ended with the departure of the last imperial troops from Roberts Heights, Pretoria (1915), and the British contingent from Simonstown (1957).

Among the Voortrekkers the Rev. Erasmus Smit and the Rev. Daniel Lindley also attended to the spiritual care of the armed burghers in time of war. During the Basuto War of 1865-66 the Free State government made provision for spiritual care in the field. During the Sekhukhune War (1876) the State President, the Rev. T. F. Burgers, held religious services in the field, while during the war of 1880-81 Transvaal ministers served as field and/or commando preachers. During the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) there were on the side of the Boers 156 chaplains, with whom a number of theological Students co-operated, in the field as well as in prisoner of-war and concentration camps. After the creation of the Union Defence Force (1912) followed by the participation of the Union in the First World War there were about 155 military chaplains, mostly fulltime, concerned with the spiritual care of the Union troops at the military bases in South Africa and on the various military fronts (German South-West Africa, German East Africa and Europe).