You are browsing the archive for Paris.

History Alive: DNA & The Rainbow Nation

June 1, 2009This research enterprise is to take DNA samples from about 500-1000 South Africans in order to trace their geographical ancestry. It will provide the first national database available in the public domain. The gene pool found in the present-day South African population draws from the indigenous people of Southern Africa, namely the former hunters or San groups, the pastoral Khoikhoi who are thought to have migrated to the Cape in the last 2,000 years introducing sheep and cattle to the region, and people originating from the Niger-Congo area speaking Nguni-languages who migrated south in the last 1,200 years. In addition, sea-borne immigrants from Western Europe (largely from the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Germany and France ), indentured labourers from India and slaves from the Malaysian Archipelago, Madagascar and other parts of Africa, have also contributed to the gene pool. Varying degrees of gene admixture between the different parental gene pools have resulted in the rich diversity of South Africans and this is evident also from the cultural and linguistic diversity of the ‘Rainbow Nation.’ We wish to provide a DNA map of the genetic heritage adding thereby an additional layer of information to our self-understanding of where we come from and who we are.

Method

Two genetic histories are recovered using mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and Y chromosome DNA testing as follows:

Maternal ancestry testing (mtDNA analysis): Females and males

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is passed on from mothers to both her sons and daughters. However, only her daughters will transmit their mtDNA in successive generations. Both males and females can be tested for mtDNA to trace their maternal ancestry. We sequence a region of about 1000 base-pairs (bp) of the mtDNA control region (also called the hypervariable region of which there are two, HVRI and HVRII). The sequence is then compared to a published reference sequence (also referred to as the Cambridge Reference Sequence, CRS) to identify the positions at which your sequence differs from the CRS. This information is used together with an internationally adopted nomenclature to identify the name of your mtDNA lineage. These lineages are also called haplogroups. Haplogroups are continent specific and subdivisions of these haplogroups have a regional geographic distribution.

Database Matches

After we obtain your mtDNA sequence and deduce the haplogroup, we then compare the sequence to a database of mtDNA sequences in individuals we have examined for our research as well as other published data collected on individuals sampled throughout the world by other researchers. This comparison allows us to find matches or close matches to one’s sequence, to give you information about the distribution of your mtDNA haplogroup, and the most likely region where your mtDNA profile originated.

Y chromosome analysis (only males)

Fathers pass on their Y chromosome to their sons only, who then pass on their Y chromosome to their sons, and so on. We make use of two types of markers on the non-recombining portion of the Y chromosome to resolve the Y chromosome lineages in males. The first type of marker, so-called bi-allelic variants (two states or alleles can be found at one site on the chromosome) is used to classify Y-chromosomes into lineages or haplogroups. These haplogroups, or major branches of the Y chromosome tree, show specific ethnic and/or geographic distribution patterns. The second type of marker, micro satellites or short tandem repeats (STRs) consist of repetitive DNA elements that are tandemly repeated and are highly variable in humans. STRs are used to define haplotypes (like a DNA fingerprint, but on the Y chromosome) within the haplogroups.

Database Matches

After we deduce your Y chromosome haplogroup, we use the STR data to derive your haplotype. We then compare your haplotype to our database and with information from a global database ( www.ystr.charite.de ). This comparison allows us to find matches or close matches to your Y chromosome lineage, to give you information about the distribution of your Y chromosome haplogroup, and the most likely region where your Y haplotype originated.

Limitations of genetic ancestry testing

The limitation of using mtDNA and Y chromosome DNA for genealogical testing is that this DNA will trace only two genetic lines on a family tree in which branches double with each preceding generation. For example, Y chromosome tracing will connect a man to his father but not his mother, and it will connect him to only one of his four grandparents: his paternal grandfather. In the same way it will connect him to one of his eight great grandparents (see figure below). Continue back in this manner for 14 generations and the man will still be connected to only one ancestor in that generation. Y-chromosome DNA testing will not connect him to any of the other 16 383 ancestors in that generation to whom he is also related in equal measure. The same scenario applies when using mtDNA.

Outcomes

• National database of the geographical ancestry of a sample of South Africans;

• Workshop to train journalists and academics to interpret the information and contribute to an edited anthology; Bringing History Alive: DNA and the Rainbow Nation.

• Special website to make ancestry information available for public use and dissemination.

Raj Ramesar is Professor and Head of the Division of Human Genetics at the University of Cape Town. He is also Director of the MRC’s Human Genetics Research Unit. Raj’s interest is in identifying those aspects of the human genome that are worth investigating for their most rapid benefit to our communities in South Africa.

Himla Soodyall is Principal Medical Scientist at the National Health Laboratory Service and holds a joint appointment as an Associate Professor in the Division of Human Genetics at the University of the Witwatersrand. She was appointed Principal Investigator of the Sub-Saharan Africa part of the global Genographic Project, a joint initiative of the National Geographic Society and IBM.

Wilmot James is Chief Executive of the Africa Genome Education Institute and Honorary Professor in the Division of Human Genetics, University of Cape Town. He is also Chairman of the Cape Philharmonic Orchestra, director of Sanlam, Media24 and the Grape Co and Trustee of the Ford Foundation of New York.

Written by: Dr Wilmot James

Anglican Archives in Port Elizabeth

May 31, 2009Use of the facility for research by members of the public: R10 for the morning plus R10 for each transcript of a Certificate. (Because a number of the registers are now very frail, some dating back to 1825, we do not make photocopies but do certify each transcript.

Research by the Archivist: Where the EXACT date and parish is known R20 including one transcript. Extra transcripts at R10 each.

General search by the Archivist: For every hour, or part thereof, that a search is conducted, including one transcript R45. Extra transcripts at R10 each. As you probably know research is very time consuming and we usually estimate a minimum of two hours.

General conditions: A minimum deposit of R45 equal to one hour’s research must be made before any research can be undertaken. The staff are all volunteers and these funds go towards the maintenance of the facility. The Archive is part of the Anglican Diocese of Port Elizabeth and we have most registers (not all) that fall within their jurisdiction, i.e. Cradock, Colesberg, Somerset East, Uitenhage, Alexandria, Humansdorp and immediate surrounds, and of course, the Anglican Parishes in Port Elizabeth, about 70 in all.

Mr Warren Morris is in charge and is assisted by Rosemary McGeoghegan and Alice Mitchley.

Postal Address:

Telephone No: 041-365-1393 & Fax: 041-365-5238.

E-mail: [email protected]

Boers

May 31, 2009Boeren Beschermings Vereeniging

(Farmers’ Protection Society)

In 1878 a section of the Afrikaans-speaking farmers of the Cape resolved to form an organisation for the purpose of ‘watching over the interests of the farmers of this Colony, and protecting the same’. It arose, in the first place, from opposition to an excise duty imposed on liquor by the Cape parliament in 1878. Later aims of the association were: ‘to endeavour to have all those with an interest in farming registered as parliamentary voters, and to watch against the abuse of the franchise’. J. H. Hofmeyr (‘Onze Jan’) was its leader and its first representative in the Legislative Assembly. On 24 May 1883 the organisation merged with the Afrikaner Bond under a new name: Afrikanerbond en Boeren Beschermings Vereeniging.

Boer Generals in Europe

During the Second Anglo-Boer War 30,000 farm houses were destroyed, and in addition 21 villages (Ermelo, Bethal, Carolina, Amsterdam, Amersfoort, Piet Retief, Paulpietersburg, Dullstroom, Roossenekal, Bloemhof, Schweizer-Reneke, Harte beestfontein, Geysdorp and Wolmaransstad in the Transvaal; Vredefort, Villiers, Parys, Lindley, Bothaville, Ventersburg and Vrede – the last mentioned partly – in the Orange Free State). In extensive areas not a single animal was to be seen. In the Free State , for instance, only 700,000 out of approximately 8,000,000 sheep remained and one tenth of the cattle. The speedy reconstruction of the former Republics was a pressing necessity. In terms of Article 10 of the Treaty of Vereeniging £3,000,000 was granted for this purpose and in addition loans at 3% (without interest for two years). This amount was considered to be totally inadequate by the representatives of the Boer people at Vereeniging, and a head committee (M. T. Steyn, Schalk Burger, Louis Botha, C. R. de Wet, J. H. de la Rey and the Revs. A. P. Kriel and J. D. Kestell) was elected on 31 May to collect further funds. Generals Botha, De Wet and De la Rey were sent to Europe for this purpose. After cordial receptions in Cape Town, Paarl and Stellenbosch they left for England on 5 Aug. 1902. Huge crowds welcomed them in London, and they were presented to King Edward VII. On the Continent they were likewise enthusiastically cheered by thousands of people. (The Hague 20 Aug., Amsterdam11 Sept., Antwerp 19 Sept., Rotterdam 22 Sept., Groningen 27 Sept., Middelburg 30 Sept., Brussels 10 Oct., Paris 13 Oct., Berlin 17 Oct.). In a letter to Joseph Chamberlain dated 23 Aug. they requested an interview to discuss, inter alia, the following matters: full amnesty for rebels; annual grants for widows and orphans; compensation for losses caused by British troops; payment of the war debts of the Republics. At the interview on 5 Sept. Chamberlain stated that if he should accede to these requests a new agreement with the Republics would have to be drawn up and that could not be done. Thereupon the Generals published on as Sept. ‘An Appeal to the Civilised World’ in which they asked for further assistance to alleviate the dire distress. The result was most disappointing. Up to Jan. 1903 the ‘Appeal’ brought in only £116,810. This was possibly due to the unwillingness of the nations to continue assisting the Boers, who were now British subjects, and to the fact that Chamberlain had announced in Parliament on 5 Nov. that the Government would grant further loans if necessary. De Wet returned to South Africa on 1 November, Botha and De la Rey on 13 December.

Boer Prisoners of War – Camps

The approximately 27,000 Boer prisoners and exiles in the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) were distributed far and wide throughout the world. They can be divided into three categories: prisoners of war, ‘undesirables’ and internees. Prisoners of war consisted exclusively of burghers captured while under arms. ‘Undesirables’ were men and women of the Cape Colony who sympathised with the Orange Free State and Transvaal Republics at war with Britain and who were therefore considered undesirable by the British. The internees were burghers and their families who had withdrawn across the frontier to Lourenço Marques at Komatipoort before the advancing British forces and had finally arrived in Portugal, where they were interned.

Prisoners of war were detained in South Africa in camps in Cape Town (Green Point) and at Simonstown (Bellevue), and some in prisons in the Cape Colony and Natal; in the Bermudas on Darrell’s, Tucker’s, Morgan’s, Burtt’s and Hawkins’ Islands; on St. Helena in the Broadbottom and Deadwood camps, and the recalcitrants in Fort Knoll; in India at Umballa, Amritsar, Sialkot, Bellary, Trichinopoly, Shahjahanpur, Ahmednagar, Kaity-Nilgris, Kakool and Bhim-Tal; and on Ceylon in Camp Diyatalawa and a few smaller camps at Ragama, Hambatota, Urugasmanhandiya and Mt. Lavinia (the hospital camp). The internees were kept in Portugal at Caldas da Rainha, Peniche and Alcobaqa. The ‘undesirables’, most of them from the Cape districts of Cradock, Middelburg, Graaf Reinet, Somerset East, Bedford and Aberdeen, were exiled to Port Alfred on the coast near Grahamstown.

In the Bermudas, on St. Helena and in South Africa quarters consisted chiefly of tents and shanties patched together from tin plate, corrugated iron sheeting, and sacking, and in India and Ceylon mostly of large sheds of corrugated iron sheeting, bamboo and reeds. The exiles, whose ages varied between y and 82 years, occupied themselves in various fields, such as church activities, cultural and educational works, sports, trade, and even printing, and nearly all of them to a greater or lesser extent took part in the making of curios.

The exiles in Ceylon and on St. Helena were the most active in printing. Using an old Eagle hand press purchased from the Ceylonese, the prisoners of war in Ceylon printed the newspaper De Strever, organ of the Christelijke Streversvereniging (Christian Endeavour Society), which appeared from Saturday, 19 Dec. 1901, to Saturday, 16 July 1902. Other newspapers, which they published, mostly printed by roneo, were De Prikkeldraad, De Krygsgevangene, Diyatalawa Dum-Dum and Diyatalawa Camp Lyre. Newspapers issued on St. Helena were De Krygsgevangene (The Captive) and Kampkruimels.

The range of the trade conducted among the prisoners of war is evident from the numerous advertisements in their newspapers. There were cafes, bakeries, confectioners, tailors, bootmakers, photographers, stamp dealers, general dealers and dealers in curios. An advertisement by R. A. T. van der Merwe, later a member of the Union Parliament, reads in translation:

Roelof v.d. Merwe, Shop No. 12, takes orders for men’s clothing. Has stocks of all requirements.

Another, by C. T. van Schalkwyk, later a Commandant and M.E.C., may be roughly translated as follows:

Here in Kerneels van Schalkwyk’s cafe a Boer

Be he rich or be he poor

For money so little its spending not felt

Can have his tummy press tight on his belt.

In religious matters the exiles in overseas camps devoted their efforts in the first place to the establishment of churches. In most of the camps building material was practically unprocurable, with the result that most of the church buildings were patched together out of corrugated iron sheets, pieces of tin, sacks, reeds and bamboo. Pulpits were constructed from planks, pieces of timber, etc. There were a number of clergymen and students of theology among the prisoners; with them in the forefront and with the help of others who had gone to the camps for this purpose, congregations were founded and church councils were elected. From these developed Christian Endeavour Societies, choirs, Sunday-school classes for the many youngsters between 9 and 16 years of age, and finally catechism classes for older youths. Many a young man was accepted as a member of the Church and confirmed while in exile. Attention was also given to mission work, and funds were collected by means of concerts, sports gatherings, etc. Many of the prisoners died in exile, and the burial services as well as the care of the graves and cemeteries were attended to by their own churches.

In the cemetery of Diyatalawa 131 lie buried, and on St. Helena 146; in the Bermudas and in India a considerable number also lie buried. Through the years the Diyatalawa cemetery has been maintained in good order by the Ceylonese. Boer prisoners of war in the Bermudas were buried on Long Island. The graves themselves are neglected and overgrown with vegetation, but the obelisk erected in the cemetery on the insistence of the returning prisoners after the conclusion of peace is still in fairly good condition. It is a simple sandstone needle on a pedestal of Bermuda stone. The names of those buried in the cemetery and those who had died at sea on the voyage to Bermuda are engraved on all four sides of the pedestal.

Cultural activities covered a number of fields. At first debating societies were formed, and from these there developed bands, choirs and dramatic groups; theatrical, choral and other musical performances were given, festive occasions such as Christmas, New Year, Dingaan’s Day (now the Day of the Covenant and the birthdays of Presidents Kruger and Steyn and of Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands were celebrated. Judging by the numerous neatly printed programmes, many of the concerts and other performances were of quite a high standard. Celebrating Dingaan’s Day at Ahmednager (India on 16 Dec. 1901 the prisoners reaffirmed the Covenant. Beautifully art-lettered in an illuminated address, the text reads in translation as follows: ‘We confess before the Lord our sin in that we have either so sorely neglected or have failed to observe Dingaan’s Day in accordance with the vow taken by our forefathers, and we this day solemnly promise Him that with His help we with our households will henceforth observe this 16th Day of December always as a Sabbath Day in His honour, and that if He spare our lives and give us and our nation the desired deliverance we shall serve Him to the end of our days …’ This oath was taken by the exiles after a month of preparation and a week of humiliation in Hut No. 7.

Education received special attention and schools were established; bearded burghers and commandants shared the school benches with young boys and youths. The subjects studied were mainly bookkeeping, arithmetic, mathematics and languages, and fellow-exiles served as instructors. It was in these schools that the foundation was laid for many a distinguished career in South Africa, such as those of a later Administrator of the Orange Free State (Comdt. C. T. M. Wilcocks), a number of clergymen, physicians and others who, after returning to their fatherland, attained great prestige and became leading figures in the Church and social and political fields. Literary works were also produced in this atmosphere of religion and culture, such as the well known poem ‘The Searchlight’, by Joubert Reitz:

When the searchlight from the gunboat

Throws its rays upon my tent

Then I think of home and comrades

And the happy days I spent

In the country where I come from

And where all I love are yet.

Then I think of things and places

And of scenes I’ll ne’er forget,

Then a face comes up before me

Which will haunt me to the last

And I think of things that have been And of happy days that’s past;

And only then I realise

How much my freedom meant

When the searchlight from the gunboat Casts its rays upon my tent.

Sports gatherings were frequently arranged and provided days of great enjoyment, when young and old competed on the sports field, while cricket, football, tennis, gymnastics and boxing matches filled many an afternoon or evening. Neatly printed programmes for the gatherings and the more important competitions were usually issued.

Various daring attempts at escape were made, but few were successful. Five exiles – Lourens Steytler, George Steytler, Willie Steyn, Piet Botha and a German named Hausner – who succeeded in swimming out to a Russian ship in the port of Colombo (Ceylon), travelled by a devious route through Russia, Germany, the Netherlands and again Germany, and finally landed at Walvis Bay. One captive on St. Helena attempted to escape by hiding in a large case marked ‘Curios’ and addressed to a fictitious dealer in London. But he was discovered shortly after the ship left port and was returned to St. Helena from Ascension Island. Of those in the Bermudas two succeeded in reaching Europe aboard ships visiting Bermudan ports, while J. L. de Villiers escaped from Trichinopoly disguised as a coolie and made his way to the French possession of Pondicherry, from which he finally reached South Africa again by a roundabout route through Aden, France and the Netherlands. Among the exiles held in Ceylon two brothers named Van Zyl and a German did not return to South Africa, but went to Java, where they developed a flourishing farm enterprise with Friesland cattle. Among those held in the Bermudas a number went to the United States of America, where in some of the states such well-known Boer names as Viljoen and Vercueil are still found.

Repatriation of Boer Prisoners of War

As early as 1901 Lord Milner realised what a stupendous task the resettlement of close on 200,000 Whites involved, among whom were about 50,000 impecunious foreigners, as well as 1000.000 Bantu who, as a result of the Anglo-Boer War, had become torn from their usual way of life and had either been herded together in prisoner-of-war and concentration camps or scattered all over the Orange Free State and the Transvaal as refugees and combatants. These people had to be restored to their shattered homes and their work in order to become self-supporting. Milner wished Britons employed by the Transvaal mines and industries to be repatriated first. This began after the annexation of the Transvaal in 1900. By Feb. 1901 as many as 12,000 had already been repatriated, and by the beginning of 1902 nearly all of them had returned to the Witwatersrand.

To aid the resettlement of former Republican subjects, special Land Boards were set up early in 1902 in both the new colonies. They were also expected to help settle immigrant British farmers. From April 1902 the repatriation sections of the Land Boards were converted into independent departments in order to prepare for the repatriation of the Afrikaner population. The post-war development of the repatriation programme was adumbrated in sections I, II and X of the peace treaty of Vereeniging. In terms of sections I and II all burghers (both ‘Bitter-enders’ and prisoners of war) were required to acknowledge beforehand the British king as their lawful sovereign. Section X read that in each district local repatriation boards would be set up to assist in providing relief and in effecting resettlement. For that the British government would provide £3m as a ‘bounty’ and loans, free of interest for two years, and after that redeemable over three years at 3 %. The wording ‘vrije gift’, as the bounty was termed, gave rise to serious misunderstanding, and the accompanying provision, that proof of war losses could be submitted to the central judicial commission, created the erroneous impression that this bounty was intended to compensate the burghers for these losses. The eventual British interpretation, that the bounty was intended as a contribution toward repatriation, created a great deal of bitterness. Eventually it turned out that there was no question of a bounty, since repatriates were held personally responsible for all costs, the £3m being part of the loan of £35m provided by the British treasury for the new colonies.

After the conclusion of peace two central repatriation boards, one in Pretoria and the other in Bloemfontein, began to function, and 38 local boards were set up in the Transvaal and 23 in the Orange River Colony. The repatriation departments were reformed into huge organisations, each employing more than 1,000 men. The real work of repatriation came under three heads, viz. getting farmers back to their farms with the least delay; supplying them with adequate rations until they could harvest their crops; and providing them with seed, stock and implements to cultivate their lands.

The general discharge of prisoners of war in South Africa began in June 1902. Many overseas prisoners of war, especially those in India, were sceptical about the peace conditions and refused to take the oath of allegiance to the British Crown. In spite of the efforts of Gen. De la Rey and Comdt. I. W. Ferreira to induce them to return, about 500 of the 900 ‘irreconcilables’ were not to be persuaded until Jan 1904.

In July 1904 the last 4 Transvaalers were discharged from India, but in May 1907 two Free Staters were still there. There were 100 men per district to every shipload, and on their arrival they were first sent to camps at Umbilo and Simonstown, where they were given food and clothing. Those who were self-supporting were allowed to go home. Through judicious selection – land-owning families first and ‘bywoners’ (share-croppers) next – repatriation was made bearable. By the middle of June 1902 almost all the ‘bitter-enders’ had laid down their arms and were allowed to return to their homes, provided they could fend for themselves. In other cases they were allowed, like the prisoners of war, to take up temporary accommodation with their families in concentration camps until they were sent home by the repatriation departments with a month’s supply of free rations, bedding, tents and kitchen utensils.

By Sept. 1902 only the impoverished group was left in the camps. In due course relief works, such as the construction of railway lines and irrigation works, were started to employ them. However, a considerable number of pre-war share-croppers became chronic Poor Whites. Spoilt by their idle mode of existence during the war, many Bantu refused to leave the refugee camps, but when their food rations were stopped they soon returned to the firms to alleviate the labour shortage.

The road to repatriation was strewn with stumbling blocks. Nearly 300,000 ruined people had to be brought back to their shattered homes. Supplies had to be conveyed over thousands of miles of impassable roads and neglected railways, already heavily burdened by the demobilisation of the British army and the transport of supplies to the Rand. Weeks of wrangling preceded the purchase from the military authorities, at exorbitant prices, of inferior foodstuffs and useless animals, many of which died. The organisation was ineffective, and the authority and ditties of the central and local repatriation boards were too vaguely defined, leading to unnecessary duplication. Moreover, the burghers mistrusted the repatriation. By the end of 1902 most of the ‘old’ population had, however, been restored. Unfortunately the long drought which dragged on from 1902 until the end of 1903 made it necessary for many of the repatriation depots to be kept going until 1904, in order to keep the starving supplied on credit. From 1904 conditions gradually began to return to normal, and in 1905 repatriation was complete. A great deal of the £ 14m spent on it had gone into administrative expenses.

Sharp criticism was levelled against the repatriation policy, especially against the incompetence and lack of sympathy among the officials, and financial mismanagement. The composition of the repatriation boards was also suspect. On the other hand, agricultural credit came in with repatriation and prepared the way for the present system of Land Bank loans and co-operative credit. Milner himself considered the repatriation a success, although he conceded that a considerable sum of money had been squandered. Yet it was not the utter failure it has often been represented to have been. Milner deserves praise for his genuine attempt to resettle an impoverished and uprooted agricultural population and to reconstruct an entire economy. The accomplishment of the entire project without serious friction can largely be attributed to the self-restraint and love of order of the erstwhile Republican burghers.

Cemeteries + Crematoria in Cape Town

May 31, 2009 The Cape Metropolitan Council welcomes genealogists to come and research in their Library but do not undertake research on anyone’s behalf. They hold burial records for the larger cemeteries such as Maitland, Plumstead, Pinelands, Ottery, Hout Bay.

The Cape Metropolitan Council welcomes genealogists to come and research in their Library but do not undertake research on anyone’s behalf. They hold burial records for the larger cemeteries such as Maitland, Plumstead, Pinelands, Ottery, Hout Bay.

Are you looking for burials in Cape Town?

| Cemetery | Location | Date Opened | Size- ha | Tel No |

| Atlantis | Old Darling Road, Atlantis | 1980 | 16.5 | 021-5721518 |

| Bellville | Strand Road, Bellville | 1947 | 13 | 021-9484541 |

| Constantia | Parish Road, Constantia | 1886 | 2.5 | 021-7031796 |

| Hout Bay | Hout Bay Main Road, Hout Bay | 1945 | 2.3 | 021-7901510 |

| Plumstead | Ext Klip Road, Grassy Park | 1938 | 10.3 | 021-7051928 |

| Maitland | Gate 1-4 Voortrekker Road, Maitland | 1886 | 100 | 021-5939592 |

| Maitland | Gate 5-10 Voortrekker Road, Maitland | 1886 | 021-5931350 | |

| Modderdam | Modderdam Road, Belhar | 1975 | 18 | 021-9346458 |

| Muizenberg | Prince George Drive, Muizenberg | 1913 | 17.1 | 021-7884758 |

| Ocean View | Jupiter Road, Ocean View | 1975 | 2.6 | 021-7831358 |

| Ottery | Ottery Road, Ottery | 1929 | 8 | 021-7035827 |

| Pinelands | No1 Forest Drive, Pinelands | 1941 | 5.8 | 021-5315062 |

| Pinelands | No2 Forest Drive, Pinelands | 1974 | 10.4 | 021-5315062 |

| Plumstead | Victoria Road, Plumstead | 1915 | 18.4 | 021-7621081 |

| Maitland | Maitland Crematorium Off Voortrekker Road, Maitland | 1934 | 021-5938316 |

Newsmakers of 1882

May 29, 2009

Jan Gysbert Hugo BOSMAN (aka Vere Bosman di Ravelli) was born in Piketberg on the 24th February 1882. He took the pseudonym di Ravelli in 1902 in Leipzig, when he began his career as a concert pianist. His father, Izak, was from the Bottelary Bosmans, and his mother Hermina (Miena) BOONZAAIER from Winkelshoek, Piketberg, which was laid out by her grandfather Petrus Johannes BOONZAAIER in 1781. One of his sisters taught him music. After taking his final B.A. examinations at Victoria College in Stellenbosch, he left for London on the 1st October 1899 aboard the Briton. Soon after arriving there, he moved to Leipzig. He performed in public for the first time in November 1902. In 1903 he gave his first concert, in Berlin, playing Chopin’s Second Piano Concerto. This was followed by a tour of Germany which launched his international career and made him the first South African international concert pianist.

In September 1905 he returned to South Africa and gave many concerts across the country. At one stage he tried to study traditional Zulu music. Amongst his friends he counted Gen. Jan SMUTS and Gustav PRELLER. He was particularly fond of old church music. He made important contributions to Die Brandwag (1910 – 1912), writing about music. There wasn’t yet enough appreciation of music in South Africa and he left for Europe on the 28th November 1910 aboard the SS Bulawayo. Travelling with him were the Afrikaans composer Charles NEL and Lionel MEIRING. They settled in Munich where he gave them piano lessons for a while. After getting his concert pianist career going again, WWI brought things to a halt. By then he was in London. When the war ended he had the Spanish flu and went to Locarno, Italy, in 1919 to recuperate. During this time he studied Arabic and Hebrew, and as a result compiled an Arabic-English glossary for the Koran. In 1921 he published a volume of English poems titled In an Italian Mirror.

He resumed his concert pianist career in 1921 in Paris, and retained Sharp’s of England as his sole agents. He made Florence his base after 1932 but lost his house there due to WWII. In February 1956 he returned to South Africa, staying with Maggie LAUBSCHER. He was made an honorary life member of the South African Academy in 1959. In 1964 he published a fable,st Theodore and the crocodile. He died on the 20th May 1967 in Somerset West.

Sydney Richfield

Sydney RICHFIELD was born on the 30th September 1882 in London, England. He learnt to play the violin and piano. In 1902 he immigrated to South Africa, like an elder brother, where he composed several popular Afrikaans songs. His first composition was the Good Hope March, which became popular and was often heard in Cape Town’s bioscopes and theatres. In 1904 he moved to Potchefstroom, where he lived until 1928. He produced operettas, revitalised the town band, and started a music school. He taught the piano, violin, mandoline and music theory. When the Town Hall was opened in 1909, he put on the operetta Paul Jones by Planquette.

In 1913 he married Mary Ann Emily LUCAS (previously married to a PRETORIUS with whom she had three daughters) and shortly afterwards the family left for England. Sydney joined the Royal Flying Corps band as a conductor in 1916. He composed an Air Force march, Ad Astra, in 1917. In 1920 he was demobilized and returned to Potchefstroom, where he started teaching again and formed a town band which played at silent movies in the Lyric Bioscope. After the band broke up in 1922, Sydney took over an amateur ensemble which included the poet Totius. Through this association, he became involved with Afrikaans music. In 1925 when Potchefstroom put on an historical pageant, he composed the Afrikaans music. By now he was also winning medals in eisteddfodau and other competitions. In 1928 he moved to Pretoria and carried on teaching and composing. He led a brass band that played at the Fountains on Sunday afternoons. Amongst his popular compositions were River Mooi, Vegkop, and Die Donker Stroom. Sydney died in Pretoria on the 12th April 1967. One of his wife’s daughters, Paula, became a popular Afrikaans singer.

Eduard Christiaan Pienaar

Eduard Christiaan PIENAAR was born on the 13th December 1882 on the farm Hoëkraal in the Potchefstroom district, the youngest of the seven sons and seven daughters of Abel Jacobus PIENAAR and Sarah Susanna BOSMAN. During the Anglo-Boer War he was part of Gen. Piet CRONJE’s commando. He was taken prisoner at Paardeberg in February 1900 and sent to St. Helena. After his release, he attended Paarl Gymnasium where he matriculated in 1904. In 1907 he graduated from Victoria College in Stellenbosch with a B.A. degree. This was followed by teaching posts in Sutherland and Franschhoek. In 1909 he married Francina Carolina MARAIS from Paarl. They had four sons and three daughters.

In 1911 he became a lecturer in Dutch at Victoria College. At the beginning of 1914, with a government bursary and the support of the Nederlandsche Zuid-Afrikaansche Vereeniging, he went to Holland, taking his wife and three children. He studied Dutch language and literature in Amsterdam and Utrecht, obtaining his doctorate in July 1919, with the thesis, Taal en poësie van die Tweede Afrikaanse Taalbeweging. The family returned to South Africa in 1920 and he became a Professor at Stellenbosch, lecturing in Dutch and Afrikaans.

The promotion of Afrikaans was his life’s passion. He was a founding member of the Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurvereniginge and served on various committees such as the Voortrekker Monument committee and the Huguenot Monument committee. It was his idea to have the symbolic ox-wagons around the Voortrekker Monument. He died in Stellenbosch on the 11th June 1949. He was returning from watching a rugby match at Coetzenburg when he had a heart attack outside his home in Die Laan.

Haji Sullaiman Shahmahomed

1882 saw the arrival of Haji Sullaiman SHAHMAHOMED from India. He was a wealthy Muslim educationalist, writer and philanthropist. He settled in Cape Town and married Rahimah, daughter of Imam SALIE, in 1888. He bought two portions of Mariendal Estate, next to the disused Muslim cemetery in Claremont, where he planned to build a mosque and academy. On the 29th June 1911 the foundation stone was laid. In terms of the trust, he appointed the Mayor of Cape Town and the Cape ‘s Civil Commissioner as co-administrators of the academy. This caused resentment among the Muslim community because the appointees were non-Muslim. The Aljamia Mosque was completed but not the academy. In August 1923 he wrote to the University of Cape Town, wanting to found a chair in Islamic Studies and Arabic, and enclosed a Union Government Stock Certificate to the value of £1 000. This trust is still active. He was very involved in the renovations of Shaykh Yusuf’s tomb at Faure in 1927, the Park Road mosque in Wynberg; and the mosque in Claremont. He died in 1927.

Professor Ritchie

William RITCHIE was born on the 12th October 1854 in Peterhead, Scotland. He came to the Cape in 1878 as a lecturer in Classics and English at the Grey Institute, Port Elizabeth. In 1882 the South African College in Cape Town appointed him to the chair of Classics, which he held until his retirement in 1930. When the College became the University of Cape Town in 1918, he became its historian. His history of the South African College appeared in two volumes in the same year. It is a valuable account of higher education in the Cape during the 19th century. He died in Nairobi on the 8th September 1931.

Thomas Charles John Bain

Thomas Charles John BAIN (1830 – 1893) completed the Homtini Pass in 1882. The pass was built largely due to the determination of the Hon. Henry BARRINGTON (1808 – 1882), a farmer and owner of the Portland estate near Knysna. Construction on the Seven Passes road from George to Knysna, ending in the Homtini Pass, started in 1867.

Thomas was the son of Andrew Geddes BAIN (1797 – 1864) and Maria Elizabeth VON BACKSTROM. His father was the only child of Alexander BAIN and Jean GEDDES. Andrew came to the Cape in 1816 from Scotland with his uncle Lt.-Col. William GEDDES of the 83rd Regiment. He went on to build eight mountain roads and passes in the Cape. Thomas was his father’s assistant during the construction of Mitchell’s Pass, and eventually built 24 mountain roads and passes. One of the very few passes not built by a BAIN in the 1800s was Montagu Pass (George to Oudtshoorn). It was built by Henry Fancourt WHITE from Australia in 1843 – 1847. Two other passes that were in construction by Thomas in 1882 were the Swartberg Pass (Oudtshoorn to Prince Albert, 1880 – 1888) and Baviaanskloof (Willowmore to Patensie, 1880 – 1890).

Henry Barrington

Portland Manor was built by Henry BARRINGTON, based on the family home Bedkett Hall in Shrivenham, England. Henry was immortalised in Daleen MATTHEE’s novel, Moerbeibos. He was the 10th son of the 5th Viscount BARRINGTON, prebendary of Durham Cathedral and rector of Sedgefield. Henry’s mother was Elizabeth ADAIR, grand-daughter of the Duke of Richmond. Henry took a law degree and was admitted to the Bar. He later joined the diplomatic service and in 1842 was sent to the Cape as legal adviser to the Chief Commissioner of British Kaffraria.

A meeting with Thomas Henry DUTHIE of Belvidere led to him buying the farm Portland from Thomas. Thomas inherited the farm from his father-in-law George REX. Henry returned to England where in 1848 he married Georgiana KNOX who was known as the Belle of Bath. They arrived at Plettenberg Bay aboard a ship laden with their family heirlooms, wedding gifts, furniture and farming equipment. They lived in a cottage while the manor house was built over 16 years. It had eight bedrooms, a library, and a large dining room. Seven children were born to them. In February 1868 the Manor was completely gutted in the forest fire that swept from Swellendam to Humansdorp. Henry rebuilt the manor using yellow wood, stinkwood and blackwood from the estate. He tried his hand, often unsuccessfully, at cattle, sheep and wheat farming in addition to bee keeping, apple and mulberry orchards. He is also credited with building the first sawmill in the area. In 1870 Henry was elected to the Cape Parliament.

He died in 1882 and the estate passed to his eldest son, John, who died unmarried in 1900. His sister Kate inherited the estate. She married Francis NEWDIGATE of Forest Hall, Plettenberg Bay, who was killed in the Anglo-Boer War. Portland Manor remained in their family until 1956, when it was bought from Miss Bunny NEWDIGATE by Seymour FROST. He started a restoration programme and eventually sold the property in 1975 to Miles PRICE-MOOR. In the 1990s the property returned to Henry’s descendants when it was owned by Jacqueline PETRIE, one of his great-grandchildren. During her ownership, Portland Manor became a guest house until it was put up for auction in 2000. It is now owned by Denis and Debbie CORNE who have restored Portland Manor once again.

Sources:

South African Music Encyclopaedia, Vol. 1 & 3; edited by J.P. Malan

Dictionary of South African Biography, Vol. II

Honey, silk and cider; by Katherine Newdigate, from Henry’s letters and journals

Timber and tides: the story of Knysna and Plettenberg Bay; by Winifred Tapson

Portland Manor: http://www.portlandmanor.com

The History of Photography at the Cape

May 29, 2009Cc

The camera obscura, an apparatus for tracing images on paper, was in common use by the 18th century as an aid to sketching. The earliest attempts to fix the images by chemical means were made in France by the Niépce brothers in I793, and in England by Thomas Wedgwood, an amateur scientist, at about the same time. Early in the 19th century further progress toward the invention of photography was being made simultaneously in France, England, Germany and Switzerland.

Of significance to photography in South Africa are the achievements of the English astronomer and scientist Sir John Herschel, who resided at the Cape from 1834 to 1838. It is thought that his experiments in connection with the development of photography advanced considerably while he lived at Feldhausen in Claremont, near Cape Town. In March 1839, only a year after his return to England, he revealed to the Royal Society the method of taking photographic pictures on paper sensitised with carbonate of silver and fixed with hyposulphite of soda. These discoveries had been accomplished independently of W. H. Fox Talbot, whose paper negative process (calotype, later called talbotype) became the basis of modern photography, and Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, whose process (daguerreotype) resulted in a positive photographic image being produced by mercury vapour on a silvered copper plate.

It is generally acknowledged that Herschel was the first to apply the terms ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ to photographic images and to use the word ‘photography’. He was also the first to imprint photographic images on glass prepared by coating with a sensitised film. Daguerre’s invention, announced in Paris in 1839, was slow in reaching the Cape; and although apparatus was advertised for sale in 1843, there is no evidence of photographs taken before 1845. The earliest extant photograph in South Africa was taken in 1845 by a Frenchman, E. Thiesson, who had photographed Daguerre himself the year before. The first portrait studio was opened in Port Elizabeth in Oct. 1846 when Jules Leger, a French daguerreotypist, arrived there from Mauritius. He took ‘photographic likenesses (a minute’s attendance)’ in a private apartment in Ring’s library, proceeding within a month to Uitenhage and Grahamstown. Leger left the country the following year, but not before his former pupil and assistant, William Ring, had succeeded him in the new art.

In Cape Town the first professional daguerreotype portraits were taken outdoors in December 1846 by the architect Carel Sparmann, at ‘all hours of the day and according to the latest improvements made in the art by himself’. He advised ladies to wear dark dresses in silk or satin, or Scotch plaid, the plaid being a pattern which showed itself with great exactness. Concerning gentlemen, the less there was of white in their clothing the greater the effect.

Daguerreotypes, usually about 5 x 8 cm in size, were bound up with a gilt mat and cover-glass to protect their fragile surfaces before being placed in velvet-lined case. The image was clearly defined, but the silver plate was costly and early Cape daguerreotypists often went bankrupt. Nevertheless they persevered in their portraiture and, to a much lesser extent, in taking views of buildings and street scenes, which were not generally for public sale until the 1800′s. Landscapes, pictorial subjects, and the early ‘news’ types of photography were at first more often the province of enthusiastic amateurs. The artisan-missionary James Cameron was experimenting with the calotype process for outdoor work before 1848, the paper negative being characterised by broad effects of light and shade. His photographs of the Anti-Convict Agitation meetings (1849) in Cape Town are the earliest known outdoor events in the Cape recorded by the camera and served as a basis for engravings made by the artist-photographer William Syme. Other early amateurs were William Groom, whose hand-coloured photograph of Wale Street, Cape Town (1852) is the earliest outdoor photograph extant in South Africa; Michael Crowly, who recorded the large number of wrecks in Table Bay (1857); and William Millard, who took the first panoramic view of Cape Town from Signal Hill (1859).

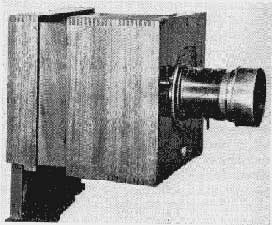

"oldest camera" in South Africa, brought to the Cape by Otto Mehliss of the German Legion (Photographic Museum, Johannesburg)

Scott Archer’s collodion process, introduced in the Cape in 1854, enabled prints to be made on sensitised paper from a collodion glass negative, resulting in a clearer rendering of half-tones. In field work the technique was particularly cumbersome as the plates had to be prepared on the spot and processed while still wet, necessitating the use of a portable dark-room such as a wagon, cart or tent. For all that, photography flourished during the collodion period, which lasted in the Cape until 1880 when James Bruton introduced the dry plate. Collodion portraits on glass (glass positives or ambrotypes) are sometimes confused with daguerreotypes, as they were made in the same sizes and fitted into similar cases. While the image of the glass positive is dull in appearance and can be seen at any angle, the daguerreotype has a shimmering, mirror-like reflecting surface which prevents the image being seen from every angle. For dating purposes professional daguerreotypy was practised in the Cape from 1846 to 1860, and glass positives were taken from 1854 until well into the 1870′s, although they were less in demand after the introduction of the carte-de-visite, a type of photograph, in 1861.

The art potential of photography was brought to public attention in 1888 at the third Fine Arts Exhibition in Cape Town. In addition to local contributions from professional and amateur photographers, there were importations from abroad. The first important use of photography for documentary purposes was achieved by William Syme and Frederick York when they published their portfolios of photographs of works of art displayed at this exhibition. No copy of either publication has as yet been traced. Earlier in the year the first general display of photographs had been held at the Grahamstown Fine Arts Exhibition, one of the organisers being the amateur photographer Dr. W. G. Atherstone, who had been present in Paris when Daguerre’s process was made public on 18 August 1839.

At the Paris Universal Exhibition in 1867 he exhibited photographs of Eastern Cape scenery, together with photographs illustrative of South African sport and travel by the explorer James Chapman, a pioneer well known for his impressive photographs of the Zambezi Expedition, which were on view at the South African Museum in 1862. An account of this expedition is given in Thomas Baines’s diary. He recounts how the photographer’s efforts were hampered in countless ways.

In the Eastern Province the majority of photographers had no fixed establishments, moving from town to town and serving a small population. Not many were as enterprising as the general dealer Henry Selby, who opened a studio in Port Elizabeth in 1854 and a branch at Uitenhage in 1855. Practising the daguerreotype, collodion and talbotype processes, he introduced stereoscopic portraits and vitrotypes (a process of producing burnt-in photographs on glass or ceramic ware), sold photographic materials and was also the first to sell views of Port Elizabeth (1856). With his partner James Hall he erected the first glass-house in the Eastern Cape (1857). This was a small wooden building with a roof consisting mainly of glass skylights and a number of panes of glass in its walls. Providing sufficient light for indoor portraiture and easily dismantled, it was especially useful to itinerant photographers. A drawback was the harsh glare of light, which irritated sitters, but more pleasing pictures were obtained by several Grahamstown photographers when they erected blue glass-houses in 1858. Arthur Green draped his with curtains.

Further progress was made in1858 with the coming of portraits on leather, card, silk, calico and oilskin. Likenesses first taken on glass and then transferred to leather won public favour immediately. They could be handled without risk of damage and could be sent overseas in a letter without additional postage charge. Documentary records of events were much in demand during Prince Alfred’s visit to South Africa in 1860. On tour he was officially accompanied by Cape Town’s leading photographer, Frederick York. The volume The progress of Prince Alfred through South Africa (Cape Town, 1861) contains seven photographs, the work of York, Joseph Kirkman and Arthur Green, whose view of Grahamstown in 1860 is the earliest known photograph of that city. These photographs were pasted in by hand. A gift of Cape views to the Prince by the Rev. W. Curtis was published in London in 1868, the Royal Edinburgh album of Cape photographs being the first major photographic work dealing exclusively with Cape scenery. Only two copies have been traced. In the 1860′s original photographs – including portraits of prominent men – were pasted in the Cape Monthly Magazine, the Eastern Province Magazine and Port Elizabeth Miscellany and the Cape Farmers’ Magazine. Several photographers, including F. York, J. Kirkman, J. E. Bruton and Arthur Green, undertook this.

Visiting Card Portrait

The introduction of the inexpensive carte-de-visite (visiting-card portrait) brought photography within reach of the masses. This new format (about 10 x 6 cm), first advertised at the Cape in 1861 at a guinea a dozen, provided the incentive for large numbers of new photographers to try their luck, often with disastrous results in smaller centres where available equipment was unsatisfactory.

The introduction of the inexpensive carte-de-visite (visiting-card portrait) brought photography within reach of the masses. This new format (about 10 x 6 cm), first advertised at the Cape in 1861 at a guinea a dozen, provided the incentive for large numbers of new photographers to try their luck, often with disastrous results in smaller centres where available equipment was unsatisfactory.

Macomo and his chief wife – attributed to William Moore South Africa, late nineteenth century 10.4 x 6.3 cm (including margins) inscribed on reverse with the title. With kind permission Michael Stevenson For more information contact +27 (0)21 461 2575 or fax +27 (0)21 421 2578 or email [email protected].

Other styles which made their appearance before 1870 were the alabastrine process (1861), an improvement on the quality of glass positives, the sennotype (1864), a chemical method of colouring photographs, and the wothly-type (1865), a specially prepared printing – out paper to increase the permanence of the photographic print.

Portrait of a woman, possibly a Cape Muslim, wearing headscarf Samuel Baylis Barnard. South Africa, late nineteenth century 10 x 6.1 cm (including margins), printed below and on reverse with photographer’s details; printed label on reverse reads: ‘From Crewes & Sons, Watchmakers & Jewellers. Cape Town.

Great strides were made toward perfecting photography between 1870 and 1880, commencing with the recording of scenes on the diamond-fields. Panoramic views of the diggings taken in 1870 by Charles Hamilton and William Roe, as well as stereoscopic views of Colesberg Kopje and camp life taken in 1872 by H. Gros, were among many that aroused interest. R. W. Murray’s The Diamond Field keepsake for 1873, a memento of photographs and letterpress sketches, was the forerunner of several albums of South African scenery first issued for publicity purposes.

The Cape landscapes of F. Hodgson, W. H. Hermann and J. E. Bruton and the published photographs of S. B. Barnard and G. Ashley are excellent examples of the high quality attained during that decade. An outstanding contribution was made by Bruton in 1874 when he recorded the transit of the planet Venus across the disc of the sun, under the direction of E. J. Stone, Astronomer Royal at the Cape.

First – class cameras and studios of increasing dimensions also provided greater facilities for portraiture, permitting large groups to be placed with ease and individuals to pose against elaborate background objects to form a pleasant picture. Few homes were without the Victorian album especially designed to present ‘cartes’ and the larger,’but not immediately as popular, cabinet portrait (approx. 15 x 10 cm) which had made its appearance at the Cape in 1867. This style was in general use from the eighties and, like the ‘carte’, remained fashionable well into the 20th century.

Sir David Gill and Charles Piazzi Smythe, astronomers at the Royal Observatory, Cape Town, made use of photography in their scientific work, Gill being the first to make a plan for a map of the sky (1882), assisted by Allis, a Mowbray photographer; and the Cape photographic Durchmusterung was produced as a pioneering venture. Smythe left South Africa after a sojourn of eight years.

The Cape Town Photographic Club mentions in 1891 that a cart was necessary for club outings in order to transport the cameras. The first meeting of that club was held on 30 October 1890 and it is the oldest photographic society in the country that has been in continuous existence. However, the Kimberley club was older, having been founded six months earlier and so being the first in the Southern Hemisphere. Amateur photographers in Port Elizabeth held their first meeting in July 1891. These three clubs were followed by others at Grahamstown, King William’s Town and Johannesburg, while before 1900 others were established at Cradock, Pietermaritzburg, Oudtshoorn, Mossel Bay, and in addition one at the South African College in Cape Town. The early pioneers of professional and commercial photography faced many difficulties and many of them were itinerant and studio photographers, of whom in the 19th century there were over 500 in the country.

In the 196os there were about 180 photographic clubs between Nairobi and the Cape, with some 5000 members, as well as tens of thousands of still and ciné photographers throughout the country.

The Second Anglo-Boer War saw the early use of X-rays, the first recorded demonstration in South Africa having been carried out by the Port Elizabeth Amateur Photographic Society in the presence of medical doctors. K. H. Gould constructed the first X-ray camera in South Africa only a year after Röntgen’s discoveries, and it was put to use when a bullet had to be extracted from Gen. Piet Cronjé’s body. Although the ciné camera was used to give an illustrated record of war scenes in the Spanish-American War in Cuba in 1898, the Second Anglo-Boer War was much more extensively covered by it in the hands of special correspondents. The British Motoscope and Biograph Co. sent out their chief technician, Laurie Dickson, with an experienced staff on 14 October 1899 on the Dunuottar Castle, on which Winston Churchill and Gen. Sir Redvers Buller also travelled. Joseph Rosenthal, Edgar M. Hyman and Sidney Goldman followed on the Arundel Castle on 2 December as representatives of the Warwick Trading Co. Tens of thousands of photographs were produced during the war, many being published in magazines and books throughout the world. The Second Anglo-Boer War could be considered to be the first war thus fully covered by still, stereo and cine photography.

G. Lindsay Johnson of Durban, an ophthalmologist, was a pioneer of colour photography, writing in the early 1900s two books on the subject, Photographic optics and colour photography and Photography in natural colour. In more recent years a pioneer in the field of applied photography has been K. G. Collender of Johannesburg, who was the inventor of mass miniature radiography, for which patents were filed in Pretoria in 1926-27, Collender thus preceding over-seas workers by several years. He was the first man in the world to produce miniature negatives of X-rays of the chest, the size of a postage stamp, with the same technique as used in full-size radiography. Collender later at the Witwatetsrand Native Labour Association in Johannesburg was capable of producing 800 miniature 70-mm films per hour, and the incredible feat has been accomplished that 3400 films were completed, together with radiological reports, in the brief space of one morning. It has been said that this plant is ten years ahead of any other in the world.

The London Society of Radiographers honoured Collender in 1962 with its honorary fellowship, the first South African so honoured.

In this space age South Africans continue to pioneer in new fields. H. W. Nicholls of Cape Town was probably the first man to photograph Sputnik I as it hurtled through space; and at Olifantsfontein in March 1958 a team of men took the first photograph of the U.S.A.’s original satellite in flight and has since recorded several other notable feats. W. S. Finsen of the State Observatory made headlines for South Africa in the field of astronomy with his unique colour photographs of Mars during its close approaches to the earth in 1954 and 1956.

Various photographers who were pioneers in their respective fields built up large collections of photographs and thus left behind them a great photographic heritage to posterity. Such photographic collections are, for example, the Arthur Elliott Collection, housed in the State Archives in Cape Town; the Duggan-Cronin Collection, in the Bantu Art Gallery in Kimberley; and the David Barnett Collection in Johannesburg. Outstanding, too, are the writings and lecture tours of Dr. A. D. Bensusan of Johannesburg, and his interpretation of various compositional structures: ‘division of fifths’ and ‘arrow-head composition’ as applied in photography, which in the U.S.A. bears the name of ‘Bensusan’s flying wedge’. He was responsible for the foundation in 1954 of the Photographic Society of South Africa and for the inauguration of its associate and fellowship qualifications. He was also the founder of the Photographic Museum and Library in Johannesburg.

Bibliography: A. D. Bemsusan Source: Standard Encylopedia of South Africa (copyright Naspers)

Faberge Hidden Family Heirlooms

March 2, 2009 Heirlooms in your family’s possession are items or artifacts that are sometimes never spoken about or even viewed, but either hidden from prying eyes or discreetly placed in the home so as not to be seen as too conspicuous to non-family members. These items can sometimes be found listed in wills or they are simply passed down through the generations with admiration and a huge amount of trust ensuring that they do not end up on an auction or in the hands of the wrong person.

Heirlooms in your family’s possession are items or artifacts that are sometimes never spoken about or even viewed, but either hidden from prying eyes or discreetly placed in the home so as not to be seen as too conspicuous to non-family members. These items can sometimes be found listed in wills or they are simply passed down through the generations with admiration and a huge amount of trust ensuring that they do not end up on an auction or in the hands of the wrong person.

Whilst sifting through the family’s boxes of memorabilia and reading wills and fascinating books – I managed to find some wonderful examples of “Hidden Family Heirlooms”.

Faberge and the Namaqualand Connection

A Johannesburg resident, Mrs. Ethel Hegedus, of Melrose, owned a Faberge Easter egg. She bought it in France circa 1947/1948 while on holiday. She was not an antique collector in the ordinary sense, she told me, she has “a few lovely things”.

The fabulous Faberge has a direct link with South Africa during the height of fashion, his partner was a South African named Allan Bowe who, according to “The Art of Faberge”, was born in Springbok.

Henry Allan Bowe (AKA Allan) was born in Caledon on 2 December 1856, son of Thomas Bowe and Brightone Elizabeth Allen from Springbok in Namaqualand.

In 1872, when his mother died, he and his siblings were sent to an Allen relative in Devonshire and then to Switzerland. Allan eventually ended up in Moscow where he worked in a jewelry shop for an Uncle. In 1886 Allan met Faberge on a train to Paris and formed the company Faberge and Bowe and decided to sell the jewelry products in Moscow in 1887.

Shops were then opened up in Duke and Bond Street assisted by Allan’s two brothers Arthur and Charles and the partnership was only dissolved in 1906, so that he was with him during the peak of his career. Otto Jarke replaced him as manager. Jarke was followed by Andrea Marchetti, an expert in silver and gems, and by 1912 the workshops were headed by Faberge’s son Alexander, until their close in 1917. In 1917 Allan had to leave Russia due to the Revolution.

The diary of Allan was given to his daughter, Mrs. E. Tomlin of Clacton-on-Sea gave this information to a Mrs. Kuttel and Snowman circa 1950. Snowman tried to contact her in 1960 but to no avail.

He was assisted by his two brothers Arthur and Charles. Arthur later set up the Faberge Branch in London.

Allan Bowe is described as having had “a remarkable flair for organisation as well as an extremely wide knowledge of his craft”.

Faberge clearly thought well of his manager, writing in 1901, ‘My friend Allan Andreevich Bowe is my assistant and first manager – he showed himself to advantage being the manager of all my business at the Moscow factory and at the branches in Moscow and Odessa for 14 years’. A presentation tray from the Forbes collection has the dates ’1890′ and ’1895′, a portrait of Allan Bowe and the Roman numeral ‘V. It is inscribed ‘To the much respected Allan Andreevich from sincerely grateful employees’. Meaning of the dates on the tray remains unresolved. It is difficult to imagine what other reference this could be than to Bowe’s service, although the newspaper advertisement and the comment by Faberge referring to fourteen years make 1887 as the year he began to work for Faberge quite clear.

Faberge clearly thought well of his manager, writing in 1901, ‘My friend Allan Andreevich Bowe is my assistant and first manager – he showed himself to advantage being the manager of all my business at the Moscow factory and at the branches in Moscow and Odessa for 14 years’. A presentation tray from the Forbes collection has the dates ’1890′ and ’1895′, a portrait of Allan Bowe and the Roman numeral ‘V. It is inscribed ‘To the much respected Allan Andreevich from sincerely grateful employees’. Meaning of the dates on the tray remains unresolved. It is difficult to imagine what other reference this could be than to Bowe’s service, although the newspaper advertisement and the comment by Faberge referring to fourteen years make 1887 as the year he began to work for Faberge quite clear.

The Argus Foreign Service

LONDON. – A silver tray once presented to Henry Bowe, the South African businessman who helped launch the famous Imperial jeweller Carl Faberge, is to go on sale here in May.

The tray is inscribed on the back with the names of all Faberge’s staff.

According to agents Phillips, who are including the piece in a major jewellery sale in Geneva, the tray is an “important and historical” piece and could fetch up to R80 000.

It will be auctioned together with fine jewels, Russian and European art objects, and works of art by Faberge himself.

(Source: Newspaper clipping from Cape Argus, Cape Town 8 April 1988)

Faberge’s work was popular in London before the firm established a branch in the city. Queen Victoria first purchased jewellery from Faberge in 1897 and Queen Alexandra, sister of the Tsarina Marie Feodorovna, collected Faberge from the 1880s onwards. Prominent members of English society were also aware of the firm. Victoria Sackville, later Lady Sackville, purchased a Faberge flower study on a visit to Russia in 1896 and recorded in her diary that ‘you meet just everyone at Faberge’. Recognising the demand for its work in England, Faberge’s representatives began to make sales trips to London in 1901. In response to the success of these trips, Arthur Bowe, an employee of Faberge’s Moscow branch named established a permanent branch in London in 1903. Bowe was an Englishman, of South African descent, whose brother Allan was Carl Faberge’s partner in Moscow. Bainbridge states that Bowe set up business in the Berners Hotel, at 6 and 7 Berners Street. Little is recorded about the branch and it is not known whether Bowe merely stayed at the hotel or if he had an office there. (Source & Acknowledgement: http://www.accessmylibrary.com/coms2/summary_0286-18035520_ITM)

Apart from the Russian royal family, the firm of Faberge had other regal clients. Other royal families placed orders for the expensive novelties made by Faberge and his firm, including King Edward VII, who bought birthday presents for Queen Alexandra from Faberge.

Slave mugs

Many years ago a silver beaker, made from 19th century Cape Rix Dollars, was owned by a Mr. S. Dyer of Ferndale, Randburg. His great grandfather was a slave-owner at the Cape. When his slaves were liberated and he received compensation he was one of the many who were “aggrieved at the meagre sum paid to them”.

To commemorate the “injustice” he sent the silver rix-dollars he received to Holland and five beakers were made from the coins – one was given to each of his sons. These items are hallmarked and bear the family initials and still remain in the family’s possession.

A historic ring that once belonged to Marie Antoinette belongs now to a Mrs. Viner of Greenside, Johannesburg. This ring was given by Marie Antoinette to a member of her Royal Bodyguard 215 years ago.

The story goes that on the 10th August 1792 the mob attacked the Tuileries and overpowered the Swiss Guards defending the apartments of Louis XVI and his 37 year old wife. Only six guards escaped and one of them was Captain Jean Henri Nicholas Jacques, a Swiss surgeon attached to the Royal Bodyguard.

Captain Jacques found refuge in England and took with him the treasured memento of the ill-fated Queen who presented the ring to him some time previously “for services rendered”. The ring bears the Royal Crest and the motto “I cherish the wound”.

On his arrival in England Captain Jacques changed his name to James and obtained a commission in the Coldstream Guards. A few years later he married an English girl and so the ring has been handed down through successive generations on condition that the ring should never be sold “except for bread”.

The Queens Doll

One of the most interesting and historic dolls in South Africa is that in the possession of Mrs. Daisy Durham, of Dundee, Northern Natal, as an heirloom. It belonged to Queen Victoria when she was a child, being one of a number she owned and liked to make clothes for. It came to South Africa as a present for Dr. Barbara Buchanan through her uncle, Herbert Buchanan, who held an official position in Kensington Palace, where Queen Victoria was born.

When the palace was being prepared for the residence of Queen Mary’s parents, and certain of Queen Victoria’s toys were selected to be kept on exhibition, this particular doll was rejected as the clockwork had ceased to function.

Mr. Buchanan then became the owner of the doll, passing it on ‘to his niece, who, in turn, passed it on to its present owner, Mrs. Durham, who is the great-niece of Dr. Barbara Buchanan. The doll has a china head, and when wound up it could walk two or three steps and could say, “Mamma, Pappa”.

The clothes worn by the doll were made in 1915 by the wife of Mr. Herbert Buchanan when she was 73, and were modelled on some worn by King Edward VII’s eldest daughter in her infancy.

Heirlooms can consists of very old paintings, drawings, knives, guns, sculptures, coins, documents, clothes, bibles or even musical instruments. There is no set category in which an item that is considered to be an heirloom can be placed.

Do you have any strange or unusual Family Heirlooms? We would love to see what you have tucked away!

Acknowledgements

Antiques and Bygones by Dennis Godfrey

Peter Gundry

Further reading on Faberge and the Namaqualand connection

Thunder on the Blaauwberg: A Book of Rare, Strange, and Curious Episodes Inspired by a Storm … – Page 109

by Lawrence George Green – 1966 – 269 pages

Allan Bowe was the name of this master jeweller. He left the Cape and went into partnership with the celebrated Carl Faberge. Jewellers all over the world…

Twice Seven – Page 217

by Henry Charles Bainbridge – 1934 – 312 pages

Faberge was right, he didn’t want a tout, he wanted a new sort of man. …

took back the cheque to Arthur Bowe, he didn’t collapse. All he said was, …

Snippet view – About this book

Handbook of the Lillian Thomas Pratt Collection: Russian Imperial Jewels – Page 17 by Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Parker Lesley – 1960 – 87 pages … in partnership with an Englishman, Allan Bowe, who had as his assistants his two …

The London house, under the joint management of Nicholas Faberge, … Snippet view – About this book

Dictionary of Enamelling – Page 53

by Erika Speel – 1998 – 152 pages The pieces made under Faberge have been described as being ‘almost the last … A branch had been established in Moscow in 1887 when Allan Bowe became a …

Quarterly Bulletin of the South African Library =: Kwartaalblad Van Die Suid-Afrikaanse Biblioteek – Page 256 by South African Library – 1946

The three Bowe brothers operated the London branch of the Faberge ” firm and then worked on their own. FH Bainbridge (who became … Snippet view – About this book

Image Captions (from top to bottom):