You are browsing the archive for Paarl.

Newsmakers of 1882

May 29, 2009

Jan Gysbert Hugo BOSMAN (aka Vere Bosman di Ravelli) was born in Piketberg on the 24th February 1882. He took the pseudonym di Ravelli in 1902 in Leipzig, when he began his career as a concert pianist. His father, Izak, was from the Bottelary Bosmans, and his mother Hermina (Miena) BOONZAAIER from Winkelshoek, Piketberg, which was laid out by her grandfather Petrus Johannes BOONZAAIER in 1781. One of his sisters taught him music. After taking his final B.A. examinations at Victoria College in Stellenbosch, he left for London on the 1st October 1899 aboard the Briton. Soon after arriving there, he moved to Leipzig. He performed in public for the first time in November 1902. In 1903 he gave his first concert, in Berlin, playing Chopin’s Second Piano Concerto. This was followed by a tour of Germany which launched his international career and made him the first South African international concert pianist.

In September 1905 he returned to South Africa and gave many concerts across the country. At one stage he tried to study traditional Zulu music. Amongst his friends he counted Gen. Jan SMUTS and Gustav PRELLER. He was particularly fond of old church music. He made important contributions to Die Brandwag (1910 – 1912), writing about music. There wasn’t yet enough appreciation of music in South Africa and he left for Europe on the 28th November 1910 aboard the SS Bulawayo. Travelling with him were the Afrikaans composer Charles NEL and Lionel MEIRING. They settled in Munich where he gave them piano lessons for a while. After getting his concert pianist career going again, WWI brought things to a halt. By then he was in London. When the war ended he had the Spanish flu and went to Locarno, Italy, in 1919 to recuperate. During this time he studied Arabic and Hebrew, and as a result compiled an Arabic-English glossary for the Koran. In 1921 he published a volume of English poems titled In an Italian Mirror.

He resumed his concert pianist career in 1921 in Paris, and retained Sharp’s of England as his sole agents. He made Florence his base after 1932 but lost his house there due to WWII. In February 1956 he returned to South Africa, staying with Maggie LAUBSCHER. He was made an honorary life member of the South African Academy in 1959. In 1964 he published a fable,st Theodore and the crocodile. He died on the 20th May 1967 in Somerset West.

Sydney Richfield

Sydney RICHFIELD was born on the 30th September 1882 in London, England. He learnt to play the violin and piano. In 1902 he immigrated to South Africa, like an elder brother, where he composed several popular Afrikaans songs. His first composition was the Good Hope March, which became popular and was often heard in Cape Town’s bioscopes and theatres. In 1904 he moved to Potchefstroom, where he lived until 1928. He produced operettas, revitalised the town band, and started a music school. He taught the piano, violin, mandoline and music theory. When the Town Hall was opened in 1909, he put on the operetta Paul Jones by Planquette.

In 1913 he married Mary Ann Emily LUCAS (previously married to a PRETORIUS with whom she had three daughters) and shortly afterwards the family left for England. Sydney joined the Royal Flying Corps band as a conductor in 1916. He composed an Air Force march, Ad Astra, in 1917. In 1920 he was demobilized and returned to Potchefstroom, where he started teaching again and formed a town band which played at silent movies in the Lyric Bioscope. After the band broke up in 1922, Sydney took over an amateur ensemble which included the poet Totius. Through this association, he became involved with Afrikaans music. In 1925 when Potchefstroom put on an historical pageant, he composed the Afrikaans music. By now he was also winning medals in eisteddfodau and other competitions. In 1928 he moved to Pretoria and carried on teaching and composing. He led a brass band that played at the Fountains on Sunday afternoons. Amongst his popular compositions were River Mooi, Vegkop, and Die Donker Stroom. Sydney died in Pretoria on the 12th April 1967. One of his wife’s daughters, Paula, became a popular Afrikaans singer.

Eduard Christiaan Pienaar

Eduard Christiaan PIENAAR was born on the 13th December 1882 on the farm Hoëkraal in the Potchefstroom district, the youngest of the seven sons and seven daughters of Abel Jacobus PIENAAR and Sarah Susanna BOSMAN. During the Anglo-Boer War he was part of Gen. Piet CRONJE’s commando. He was taken prisoner at Paardeberg in February 1900 and sent to St. Helena. After his release, he attended Paarl Gymnasium where he matriculated in 1904. In 1907 he graduated from Victoria College in Stellenbosch with a B.A. degree. This was followed by teaching posts in Sutherland and Franschhoek. In 1909 he married Francina Carolina MARAIS from Paarl. They had four sons and three daughters.

In 1911 he became a lecturer in Dutch at Victoria College. At the beginning of 1914, with a government bursary and the support of the Nederlandsche Zuid-Afrikaansche Vereeniging, he went to Holland, taking his wife and three children. He studied Dutch language and literature in Amsterdam and Utrecht, obtaining his doctorate in July 1919, with the thesis, Taal en poësie van die Tweede Afrikaanse Taalbeweging. The family returned to South Africa in 1920 and he became a Professor at Stellenbosch, lecturing in Dutch and Afrikaans.

The promotion of Afrikaans was his life’s passion. He was a founding member of the Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurvereniginge and served on various committees such as the Voortrekker Monument committee and the Huguenot Monument committee. It was his idea to have the symbolic ox-wagons around the Voortrekker Monument. He died in Stellenbosch on the 11th June 1949. He was returning from watching a rugby match at Coetzenburg when he had a heart attack outside his home in Die Laan.

Haji Sullaiman Shahmahomed

1882 saw the arrival of Haji Sullaiman SHAHMAHOMED from India. He was a wealthy Muslim educationalist, writer and philanthropist. He settled in Cape Town and married Rahimah, daughter of Imam SALIE, in 1888. He bought two portions of Mariendal Estate, next to the disused Muslim cemetery in Claremont, where he planned to build a mosque and academy. On the 29th June 1911 the foundation stone was laid. In terms of the trust, he appointed the Mayor of Cape Town and the Cape ‘s Civil Commissioner as co-administrators of the academy. This caused resentment among the Muslim community because the appointees were non-Muslim. The Aljamia Mosque was completed but not the academy. In August 1923 he wrote to the University of Cape Town, wanting to found a chair in Islamic Studies and Arabic, and enclosed a Union Government Stock Certificate to the value of £1 000. This trust is still active. He was very involved in the renovations of Shaykh Yusuf’s tomb at Faure in 1927, the Park Road mosque in Wynberg; and the mosque in Claremont. He died in 1927.

Professor Ritchie

William RITCHIE was born on the 12th October 1854 in Peterhead, Scotland. He came to the Cape in 1878 as a lecturer in Classics and English at the Grey Institute, Port Elizabeth. In 1882 the South African College in Cape Town appointed him to the chair of Classics, which he held until his retirement in 1930. When the College became the University of Cape Town in 1918, he became its historian. His history of the South African College appeared in two volumes in the same year. It is a valuable account of higher education in the Cape during the 19th century. He died in Nairobi on the 8th September 1931.

Thomas Charles John Bain

Thomas Charles John BAIN (1830 – 1893) completed the Homtini Pass in 1882. The pass was built largely due to the determination of the Hon. Henry BARRINGTON (1808 – 1882), a farmer and owner of the Portland estate near Knysna. Construction on the Seven Passes road from George to Knysna, ending in the Homtini Pass, started in 1867.

Thomas was the son of Andrew Geddes BAIN (1797 – 1864) and Maria Elizabeth VON BACKSTROM. His father was the only child of Alexander BAIN and Jean GEDDES. Andrew came to the Cape in 1816 from Scotland with his uncle Lt.-Col. William GEDDES of the 83rd Regiment. He went on to build eight mountain roads and passes in the Cape. Thomas was his father’s assistant during the construction of Mitchell’s Pass, and eventually built 24 mountain roads and passes. One of the very few passes not built by a BAIN in the 1800s was Montagu Pass (George to Oudtshoorn). It was built by Henry Fancourt WHITE from Australia in 1843 – 1847. Two other passes that were in construction by Thomas in 1882 were the Swartberg Pass (Oudtshoorn to Prince Albert, 1880 – 1888) and Baviaanskloof (Willowmore to Patensie, 1880 – 1890).

Henry Barrington

Portland Manor was built by Henry BARRINGTON, based on the family home Bedkett Hall in Shrivenham, England. Henry was immortalised in Daleen MATTHEE’s novel, Moerbeibos. He was the 10th son of the 5th Viscount BARRINGTON, prebendary of Durham Cathedral and rector of Sedgefield. Henry’s mother was Elizabeth ADAIR, grand-daughter of the Duke of Richmond. Henry took a law degree and was admitted to the Bar. He later joined the diplomatic service and in 1842 was sent to the Cape as legal adviser to the Chief Commissioner of British Kaffraria.

A meeting with Thomas Henry DUTHIE of Belvidere led to him buying the farm Portland from Thomas. Thomas inherited the farm from his father-in-law George REX. Henry returned to England where in 1848 he married Georgiana KNOX who was known as the Belle of Bath. They arrived at Plettenberg Bay aboard a ship laden with their family heirlooms, wedding gifts, furniture and farming equipment. They lived in a cottage while the manor house was built over 16 years. It had eight bedrooms, a library, and a large dining room. Seven children were born to them. In February 1868 the Manor was completely gutted in the forest fire that swept from Swellendam to Humansdorp. Henry rebuilt the manor using yellow wood, stinkwood and blackwood from the estate. He tried his hand, often unsuccessfully, at cattle, sheep and wheat farming in addition to bee keeping, apple and mulberry orchards. He is also credited with building the first sawmill in the area. In 1870 Henry was elected to the Cape Parliament.

He died in 1882 and the estate passed to his eldest son, John, who died unmarried in 1900. His sister Kate inherited the estate. She married Francis NEWDIGATE of Forest Hall, Plettenberg Bay, who was killed in the Anglo-Boer War. Portland Manor remained in their family until 1956, when it was bought from Miss Bunny NEWDIGATE by Seymour FROST. He started a restoration programme and eventually sold the property in 1975 to Miles PRICE-MOOR. In the 1990s the property returned to Henry’s descendants when it was owned by Jacqueline PETRIE, one of his great-grandchildren. During her ownership, Portland Manor became a guest house until it was put up for auction in 2000. It is now owned by Denis and Debbie CORNE who have restored Portland Manor once again.

Sources:

South African Music Encyclopaedia, Vol. 1 & 3; edited by J.P. Malan

Dictionary of South African Biography, Vol. II

Honey, silk and cider; by Katherine Newdigate, from Henry’s letters and journals

Timber and tides: the story of Knysna and Plettenberg Bay; by Winifred Tapson

Portland Manor: http://www.portlandmanor.com

History of Cycling in South Africa

May 29, 2009 No history of cycling in South Africa would be complete without tribute being paid to probably our greatest cyclist, Laurens S. Meintjes, who became champion of the world on 15th August 1893 in Chicago, and won numerous races in Britain. Meintjes was an outstanding rider in the Transvaal in 1891, and, in the following two years he rightly qualified for the honour of being undisputed champion of South Africa. Most of the cycling clubs in South Africa organised meetings during 1893 to defray the expense of sending Meintjes to Britain and America, where he was to meet the best riders in the world. The young Springbok, unheralded and unsung, rode brilliantly in America and established world’s, records for distances from three to 50 miles. He returned to South Africa, where he again dominated the scene in 1894, but this was his last competitive season. He was in business on his own and found that he could not find time to ride and keep his business going, and South Africa lost the services of a great rider in his prime.

No history of cycling in South Africa would be complete without tribute being paid to probably our greatest cyclist, Laurens S. Meintjes, who became champion of the world on 15th August 1893 in Chicago, and won numerous races in Britain. Meintjes was an outstanding rider in the Transvaal in 1891, and, in the following two years he rightly qualified for the honour of being undisputed champion of South Africa. Most of the cycling clubs in South Africa organised meetings during 1893 to defray the expense of sending Meintjes to Britain and America, where he was to meet the best riders in the world. The young Springbok, unheralded and unsung, rode brilliantly in America and established world’s, records for distances from three to 50 miles. He returned to South Africa, where he again dominated the scene in 1894, but this was his last competitive season. He was in business on his own and found that he could not find time to ride and keep his business going, and South Africa lost the services of a great rider in his prime.

Laurens Meintjies was born in Aberdeen on 9th June 1868 and married in Graaff-Reinet on 14th August 1894 to Rowena Augusta Watermeyer. He married again in 1927 to Reid Smith. Meintjies was in the Cape Town Highlanders during the Anglo Boer War and died on 30th March 1941 in Potgietersust.

Cycling was a popular pastime before the South African War, and excellent tracks were laid down at Cape Town, Kimberley, Port Elizabeth, Grahamstown, Maritzburg, Durban and Johannesburg, the Cape Town track and ground costing £10,000, which was provided out of Corporation funds. A track was subsequently laid down at Pretoria, and it is no wonder that cycling occupied a prominent place in the sporting calendar. In fact the sport became almost too popular, and malpractices crept in which resulted in many unseemly scenes. In an effort to cleanse the sport the South African Cyclists’ Union was formed in 1892 – two years before the national athletic association was founded – and in 1897 the Transvaal Cyclists’ Union came into being to control cycling in the Province. The work of these two controlling bodies played a big part in furthering cycling throughout the country, and it was largely due to their efforts that it prospered.

The first national cycling championships were held at Johannesburg on 9 September, 1893, when, although L. S. Meintjes and another magnificent rider, H. Papenfus, were absentees, the riding reached a high standard. It was at this meeting that Mr. S. Lavine, the chief timekeeper, used a special stop chronometer endorsed “specially good” by the Kew authorities, and marked “Kew A.”

After the historic tour of Britain and America by L. S. Meintjes, the next South African cyclist to go overseas was J. M. Griebenow, who rode in the big meetings in Britain in 1898. Although he did not succeed in recapturing his best form, he rode well without winning a major race.

Four cyclists, F. Shore, F. T. Venter, P. T. Freylinck and T. H. E. Passmore accompanied the Springbok team to the 1908 Olympic Games in London, but we had to wait until the following Games, at Stockholm, in 1912, before a Springbok won an Olympic title. Randolph Lewis, our lone cycling representative, rode a grand race in the 200 kilometres road race to beat the best men in the world.

In the following year W. R. Smith, riding in the 100 miles tandem-paced cycling championship in Britain, won the event and also broke the world’s record for four hours, during which he covered 108 miles, 1,000 yards.

By this time the Springboks had established, a reputation for road cycling and distance events, and cyclists have been included in most Springbok teams competing overseas. Among the outstanding men who have worn the green and gold colours are H. Kaltenbrun, who was second in the road race at the 1920 Olympiad, George Thursfield, a wonderful sprinter, J. L. Walker, H. W. Goosen, F. Short, E. Clayton, H. Binneman, who competed at the 1936 Games at Berlin and won the British Empire road race at Sydney in 1938, and Sid Rose, who was third in the 10 miles event at Sydney. Undoubtedly the greatest incentive given to cycling was the tour in February and March, 1948, of the British cycling team. The visitors were all outstanding cyclists and, when they were not actually riding, passed on valuable tips to our own men. Lectures were given, improvements to machines were suggested, tactics were explained, and it is evident that our own men will show considerable improvement as a direct result of this pleasant and instructive visit. In the only test match of the tour, at Kimberley, the visitors did not lose a’ single event, but the improvement shown by our own riders was remarkable.

There is a feeling among cyclists that they should have their own union, and it is quite possible that in the near future the South African Cyclists’ Union will be resuscitated. The breakaway from the South African Amateur Athletic and Cycling Association will be on amicable lines and should be in the best interests of both athletics and cycling.

Bicycle races were held in South Africa some years before Dunlop invented the pneumatic tyre (patented 1888). The first cycling club in Southern Africa – the Port Elizabeth Bicycle Club – was founded in October 1881, while the South African Amateur Cycling Union was founded in 1892 in Johannesburg. On 9 September 1893 the first South African championships were decided in Johannesburg, and in the same year the first world championships.

Cycling prospered particularly on the Witwatersrand. Men like L. S. Meintjes, J. D. Celliers, L. C. Papenfus, C. H. Kincaid, F. G. Connock, H. Newby-Fraser, C. E. Brink and J. M. Griebenow were the pioneers of a sound cycling tradition. Lourens Meintjes, who used the first racing bicycle fitted with pneumatic tyres in Johannesburg, achieved high honours in 1893 in Europe and the U.S.A. Between 12 August and 11 September at Chicago and Springfield, Mass., respectively, he won five world titles and established sixteen world records over distances from 3 to 50 miles (4.8 to 80.5 km). His victories acted as a spur to cycling throughout South Africa. Many types of races were held, one the ‘Wacht-eenBeetje’.

In 1897 the S.A. Cycling Union consisted of 39 affiliated clubs. Every city and even small towns like Paarl had or were constructing a cycling track. In the same year the Cape Town firm of Donald Menzies & Co. manufactured the Springbuck cycle.

This is the first reference to the springbok in South African sport. In 1905 the S.A. Cycling Union and the S.A. Athletic Union merged and the S.A. Amateur Athletic and Cycling Association was formed. This singular ‘marriage’ was dissolved in 1958 after 53 years of fruitful co-operation. Since then cycling has been controlled by the S.A. Amateur Cycling Federation.

Two important clubs are the City Cycling Club of Cape Town (1891) and the Paarl Amateur Athletic and Cycling Club (1894). In 1897 the former had 260 members and in the same year the Paarl Club staged its first Boxing Day meeting. No cycling race in South Africa has a more colourful tradition than the race over 2,5 miles (40.2 km) held annually at this meeting. Dirk Binneman, member of South Africa’s best-known cycling family, is the only cyclist who has won this race four years consecutively (1942-1945).

Two important clubs are the City Cycling Club of Cape Town (1891) and the Paarl Amateur Athletic and Cycling Club (1894). In 1897 the former had 260 members and in the same year the Paarl Club staged its first Boxing Day meeting. No cycling race in South Africa has a more colourful tradition than the race over 2,5 miles (40.2 km) held annually at this meeting. Dirk Binneman, member of South Africa’s best-known cycling family, is the only cyclist who has won this race four years consecutively (1942-1945).

In 1908 in London four cyclists (F. Shore, F. T. Venter, P. T. Freylinck and T. H. E. Passmore) represented South Africa at the Olympic Games for the first time. Four years later at the Olympic Games in Stockholm a mine-worker from Johannesburg, Rudolph Lewis, scored the first Olympic cycling victory for South Africa. He won the gold medal in the road race over 320 kilometres (198 miles 1,478 yd), beating 134 opponents in 10 hrs. 42 min. 39 sec.

In the years before and after the First World War South African cycling was dominated by five men: H. W. Goosen, W. R. Smith, G. E. Thursfield, H. J. Kaltenbrun and J. R. Walker. At the Olympic Games in 1920 the last four each won a silver medal. Touring Australia and New Zealand in 1921-22, Kaltenbrun and Thursfield won a total of 34 races. From 1920 to 1930 most major honours were shared by the Paarl riders A. J. Basson, F. W. Short, A. J. Louw and I. Roux. At the South African championships in 1928 Short won all the titles except the 10 miles (16 km), won by his clubmate Louw. In the next ten years H. Binneman, T. Clayton and S. Rose of Cape Town were the top riders. At the Empire and Commonwealth Games in 1938 at Sydney, Binneman won the gold medal in the road race over loo kilometres (2 hrs. 53 min. 29.6 sec.). The first visit from overseas was in 1948, by a British team captained by L. Pond. This gave an added incentive to the sport in South Africa, and the standard of track cycling was raised considerably. The visitors won the only test, at Kimberley, by 33-8. The tables were turned when a second British team, under T. Godwin, visited South Africa in 1952; South Africa won both tests. In the same year at the Olympic Games in Helsinki two silver medals were won by T. Shardelow, a silver and a bronze medal by R. Robinson, and a silver medal each by J. Swift, R. Fowler and G. Estman. This gave South Africa the third place in world ranking on the basis of the unofficial Olympic cycling scoreboard.

In Rhodesia cycling was established early in the century, and in Mozambique after the First World War. D. H. B. McKenzie of Salisbury won 43 Rhodesian and 4 South African titles (1931- 1948).

Non-White cyclists, particularly Coloured men in the Cape, took up the sport in growing numbers after the First World War. In 1949 the S.A. Amateur Athletic and Cycling Association (Non-European) was founded, and in 1958 it became affiliated to the governing bodies of athletics and cycling in South Africa. The first South African cycling championships for non-Whites were decided in Durban in 1957.

ARRIE JOUBERT BIBL. G. A. Parker: South African sports (1897).

The First Burghers at the Cape

May 28, 2009 The preliminary arrangements for releasing some of the Company’s servants from their engagements and helping them to become farmers were at length completed, and on the 21st of February 1657 ground was allotted to the first burghers in South Africa. Before that date individuals had been permitted to make gardens for their own private benefit, but these persons still remained in the Company’s service. They were mostly petty officers with families, who drew money instead of rations, and who could derive a portion of their food from their gardens, as well as make a trifle occasionally by the sale of vegetables. The free burghers, as they were afterwards termed, formed a very different class, as they were subjects, not servants of the Company. For more than a year the workmen as well as the officers had been meditating upon the project, and revolving in their minds whether they would be better off as free men or as servants. At length nine of them determined to make the trial. They formed themselves into two parties, and after selecting ground for occupation, presented themselves before the Council and concluded the final arrangements. There were present that day at the Council table in the Commander’s hall, Mr Van Riebeek, Sergeant Jan van Harwarden, and the Bookkeeper Roelof de Man. The proceedings were taken down at great length by the Secretary Caspar van Weede.

The preliminary arrangements for releasing some of the Company’s servants from their engagements and helping them to become farmers were at length completed, and on the 21st of February 1657 ground was allotted to the first burghers in South Africa. Before that date individuals had been permitted to make gardens for their own private benefit, but these persons still remained in the Company’s service. They were mostly petty officers with families, who drew money instead of rations, and who could derive a portion of their food from their gardens, as well as make a trifle occasionally by the sale of vegetables. The free burghers, as they were afterwards termed, formed a very different class, as they were subjects, not servants of the Company. For more than a year the workmen as well as the officers had been meditating upon the project, and revolving in their minds whether they would be better off as free men or as servants. At length nine of them determined to make the trial. They formed themselves into two parties, and after selecting ground for occupation, presented themselves before the Council and concluded the final arrangements. There were present that day at the Council table in the Commander’s hall, Mr Van Riebeek, Sergeant Jan van Harwarden, and the Bookkeeper Roelof de Man. The proceedings were taken down at great length by the Secretary Caspar van Weede.

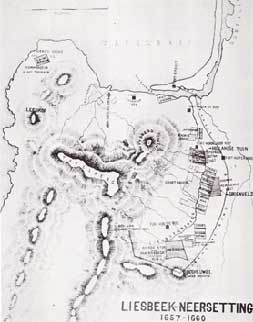

The first party consisted of five men, named Herman Remajenne, Jan de Wacht, Jan van Passel, Warnar Cornelissen, and Roelof Janssen. They had selected a tract of land just beyond Liesbeek, and had given to it the name of Groeneveld, or the Green Country. There they intended to apply themselves chiefly to the cultivation of wheat. And as Remajenne was the principal person among them, they called themselves Herman’s Colony. The second party was composed of four men, named Stephen Botma, Hendrik Elbrechts, Otto Janssen, and Jacob Cornelissen. The ground of their selection was on this side of the Liesbeek, and they had given it the name of Hollandsche Thuin, or the Dutch Garden. They stated that it was their intention to cultivate tobacco as well as grain. Henceforth this party was known as Stephen’s Colony. Both companies were desirous of growing vegetables and of breeding cattle, pigs, and poultry.

The conditions under which these men were released from the Company’s service were as follows :

They were to have in full possession all the ground which they could bring under cultivation within three years, during which time they were to be free of taxes. After the expiration of three years they were to pay a reasonable land tax. They were then to be at liberty to sell, lease, or otherwise alienate their ground, but not without first communicating with the Commander or his representative. Such provisions as they should require out of the magazine were to be supplied to them at the same price as to the Company’s married servants. They were to be at liberty to catch as much fish in the rivers as they should require for their own consumption.

They were to be at liberty to sell freely to the crews of ships any vegetables which the Company might not require for the garrison, but they were not to go on board ships until three days after arrival, and were not to bring any strong drink on shore. Called Stephen Janssen, that is Stephen the son of John, in the records of the time. More than twenty years later he first appears as Stephen Botma. From him sprang the present large South African family of that name.

They were not to keep taps, but were to devote themselves to the cultivation of the ground and the rearing of cattle. They were not to purchase horned cattle, sheep, or anything else from the natives, under penalty of forfeiture of all their possessions.

They were to purchase such cattle as they needed from the Company, at the rate of twenty-five gulden for an ox or cow and three gulden for a sheep.

They were to sell cattle only to the Company, but all they offered were to be taken at the above prices.

They were to pay to the Company for pasturage one tenth of all the cattle reared, but under this clause no pigs or poultry were to be claimed.

The Company was to furnish them upon credit, at cost price in the Fatherland, with all such implements as were necessary to carry on their work, with food, and with guns, powder, and lead for their defence. In payment they were to deliver the produce of their ground, and the Company was to hold a mortgage upon all their possessions.

They were to be subject to such laws as were in force in the Fatherland and in India, and to such as should thereafter be made for the service of the Company and the welfare of the community. These regulations could be altered or amended at will by the Supreme Authorities. The two parties immediately took possession of their ground and commenced to build themselves houses.

They had very little more than two months to spare before the rainy season would set in, but that was sufficient time to run up sod walls and cover them with roofs of thatch. The forests from which timber was obtained were at no great distance; and all the other materials needed were close at hand. And so they were under shelter and ready to turn over the ground when the first rains of the season fell. There was a scarcity of farming implements at first, but that was soon remedied.

On the 17th of March a ship arrived from home, having on board an officer of high rank, named Ryklof van Goens, who was afterwards Governor General of Netherlands India, He had been instructed to rectify anything that he might find amiss here, and he thought the conditions under which the burghers held their ground could be improved. He therefore made several alterations in them, and also inserted some fresh clauses, the most important of which are as follows:

1. The freemen were to have plots of land along the Liesbeek, in size forty roods by two hundred – equal to 133 morgen – free of fixes for twelve years.

2. All farming utensils were to be repaired free of charge for three years. In order to procure a good stock of breeding cattle, the free-men were to be at liberty to purchase from the natives, until further instructions should be received, but they were not to pay more than the Company.

3. The price of horned cattle between the freemen and the Company was reduced from twenty-five to twelve gulden.

The penalty to be paid by a burgher for selling cattle except to the Company was fixed at twenty rix-dollars.

4. That they might direct their attention chiefly to the cultivation of grain, the freemen were not to plant tobacco or even more vegetables than were needed for their own consumption.

5. The burghers were to keep guard by turns in any redoubts which should be built for their protection.

6. They were not to shoot any wild animals except such as were noxious. To promote the destruction of ravenous animals the premiums were increased, viz, for a lion, to twenty-five gulden, for a hyena, to twenty gulden, and for a leopard, to ten gulden.

7. None but married men of good character and of Dutch or German birth were to have ground allotted to them. Upon their request, their wives and children were to be sent to them from Europe. In every case they were to agree to remain twenty years in South Africa.

8. Unmarried men could be released from service to work as mechanics, or if they were specially adapted for any useful employment, or if they would engage themselves for a term of years to the holders of ground.

9. One of the most respectable burghers was to have a seat and a vote in the Council of Justice whenever cases affecting freemen or their interests were being tried. He was to hold the office of Burgher Councillor for a year, when another should be selected and have the honour transferred to him.

To this office Stephen Botma was appointed for the first term. The Commissioner drew up lengthy instructions for the guidance of the Cape government, in which the Commander was directed to encourage and assist the burghers, as they would relieve the Company of the payment of a large amount of wages. There were then exactly one hundred persons in South Africa in receipt of wages, and as soon as the farmers were sufficiently numerous, this number was to be reduced to seventy.

Many of the restrictions under which the Company’s servants became South African burghers were vexatious, and would be deemed intolerable at the present day. But in 1657 men heard very little of individual rights or of unrestricted trade. They were accustomed to the interference of the government in almost every thing, and as to free trade, it was simply impossible. The Netherlands could only carry on commerce with the East by means of a powerful Company, able to conduct expensive wars and maintain great fleets without drawing upon the resources of the State. Individual interests were therefore lost sight of even at home, much more so in such a settlement as that at the Cape, which was called into existence by the Company solely and entirely for its own benefit.

A commencement having been made, there were a good many applications for free papers. Most of those to whom they were granted afterwards re-entered the Company’s service, or went back to the Fatherland. The names of some who remained in South Africa have died out, but others have numerous descendants in this country at the present day. There are even instances in which the same Christian name has been transmitted from father to son in unbroken succession. In addition to those already mentioned, the following individuals received free papers within the next twelvemonth : Wouter Mostert, who was for many years one of the leading men in the settlement. He had been a miller in the Fatherland, and followed the same occupation here after becoming a free burgher. The Company had imported a corn mill to be worked by horses, but after a short time it was decided to make use of the water of the fresh river as a motive power. Mostert contracted to build the new mill, and when it was in working order he took charge of it on. shares of the payments made for grinding. Hendrik Boom, the gardener, whose name has already been frequently mentioned.

Caspar Brinkman, Pieter Visagie, Hans Faesbenger, Jacob Cloete, Jan Reyniers, Jacob Theunissen, Jan Rietvelt, Otto van Vrede, and Simon Janssen, who had land assigned to them as farmers. Herman Ernst, Cornelis Claassen, Thomas Robertson (an Englishman), Isaac Manget, Klaas Frederiksen, Klaas Schriever, and Hendrik Fransen, who took service with farmers.

Christian Janssen and Peter Cornelissen, who received free papers because they had been expert hunters in the Company’s service. It was arranged that they should continue to follow that employment, in which they were granted a monopoly, and prices were fixed at which they were to sell all kinds of game they were also privileged to keep a tap for the sale of strong drink.

Leendert Cornelissen, a ship’s carpenter, who received a grant of a strip of forest at the foot of the mountain. His object was to cut timber for sale, for all kinds of which pries were fixed by the Council.

Elbert Dirksen and Hendrik van Surwerden, who were to get living as tailor.

Jan Vetteman, the surgeon of the fort. He arranged for a monopoly of practice in his profession and for various other privileges.

Roelof Zieuwerts, who was to get his living as a waggon and plough maker, and to whom a small piece of forest was granted.

Martin Vlockaart, Pieter Jacobs, and Jan Adriansen, who were to maintain themselves as fishermen.

Pieter Kley, Dirk Vreem, and Pieter Heynse, who were to saw yellow wood planks for sale, as well as to work at their occupation as carpenters’.

Hendrik Schaik, Willem Petersen, Dirk Rinkes, Michiel van Swel, Dirk Noteboom, Frans Gerritsen, and Jan Zacharias, who are mentioned merely as having become free burghers. Besides the regulations concerning the burghers, the Commissioner Van Goons drew up copious instructions on general subjects for the guidance of the government. He prohibited the ompany’s servants from cultivating larger gardens than required or their own use, but he excepted the Commander, to whom he granted the whole of the ground at Green Point as a private farm. As a rule, the crews of foreign ships were not to be provided with vegetables or meat, but were to be permitted to take in water freely. The Commander was left some discretion in dealing with hem, but the tenor of the instructions was that they were not to be, encouraged to visit Table Bay.

Regarding the natives, they were to be treated kindly, so as to obtain their goodwill. If any of them assaulted or robbed a burgher, those suspected should be seized and placed upon Robben Island until they made known the offenders, when they should be released and the guilty persons be banished to the island for two or three years. If any of them committed murder, the criminal should be put to death, but the Commander should endeavour have the execution performed by the natives themselves. Caution was to be observed that no foreign language should continue to be spoken by any slaves who might hereafter be brought into the country. Equal care was to be taken that no other weights or measures than those in use in the Fatherland should be introduced. The measure of length was laid down as twelve Rhynland inches to the foot, twelve-feet to the rood, and two thousand roods to the mile, so that fifteen miles would be equal to a degree of latitude. In measuring land, six hundred square roods were to make a morgen. The land measure thus introduced is used in the Cape Colony to the present day. In calculating with it, it must be remembered that one thousand Rhynland feet are equal to one thousand and thirty-three British Imperial feet. The office of Secunde, now for a long time vacant, was filled by the promotion of the bookkeeper Roelof de Man. Caspar van Weede was sent to Batavia, and the clerk Abraham Gabbema was appointed Secretary of the Council in his stead. In April 1657, when these instructions were issued, the European population consisted of one hundred and thirty-four individuals, Company’s servants and burghers, men, women, and children all told. There were at the Cape three male and eight female slaves.

Commissioner Van Goens permitted the burghers to purchase cattle from the natives, provided they gave in exchange no more than the Company was offering. A few weeks after he left South Africa, three of the farmers turned this license to account, by equipping themselves and going upon a trading journey inland. Travelling in an easterly direction, they soon reached a district in which five or six hundred Hottentots were found, by whom they were received in a friendly manner. The Europeans could not sleep in the huts on account of vermin and filth, neither could they pass the night without some shelter, as lions and other wild animals were numerous in that part of the country. The Hottentots came to their assistance by collecting a great quantity of thorn bushes, with which they formed a high circular hedge, inside of which the strangers slept in safety. Being already well supplied with copper, the residents were not disposed to part with cattle, and the burghers were obliged to return with only two oxen and three sheep. They understood the natives to say that the district in which they were living was the choicest portion of the whole country, for which reason they gave it the name of Hottentots Holland.

For many months none of the pastoral Hottentots had been at the fort, when one day in July Harry presented himself before the Commander. He had come, he said, to ask where they could let their cattle graze, as they observed that the Europeans were cultivating the ground along the Liesbeek. Mr Van Riebeek replied that they had better remain where they were, which was at distance of eight or ten hours’ journey on foot from the fort. Harry informed him that it was not their custom to remain long in one place, and that if they were deprived of a retreat here they would soon be ruined by their enemies. The Commander then rated that they might come and live behind the mountains, along by Hout Bay, or on the slope of the Lion’s Head, if they would trade with him. But to this Harry would not consent, as he said they lived upon the produce of their cattle. The native difficulty had already become what it has been ever since, the most important question for solution in South Africa. Mr Van Riebeek was continually devising some scheme for its settlement, and a large portion of his dispatches has reference to the subject. At this time his favourite plan was to build a chain of redoubts across the isthmus and to connect them with a wall.

A large party of the Kaapmans was then to be enticed within the line, with their families and cattle, and when once on this side none but men were ever to be allowed to go beyond it again. They were to be compelled to sell their cattle, but were to be provided with goods so that the men could purchase more, and they were to be allowed a fair profit on trading transactions. The women and children were to be kept as guarantees for the return of the men. In this manner, the Commander thought, a good supply of cattle could be secured, and all difficulties with the natives be removed.

During the five years of their residence at the Cape, the Europeans had acquired some knowledge of the condition of the natives. They had ascertained that all the little clans in the neighbourhood, whether Goringhaikonas, Gorachouquas, or Goringhaiquas, were members of one tribe, of which Gogosoa was the principal chief. The clans were often at war, as the Goringhaikonas and the Goringhaiquas in 1652, but they showed a common front against the next tribe or great division of people whose chiefs owned relationship to each other. The wars between the clans usually seemed to be mere forays with a view of getting possession ‘of women and cattle, while between the tribes hostilities were often waged with great bitterness. Of the inland tribes, Mr Van Riebeek knew nothing more than a few names. Clans calling themselves the Chariguriqua, the Cochoqua, and the Chainouqua had been to the fort, and from the last of these one hundred and thirty head of cattle had recently been purchased, but as yet their position with regard to others was not made out. The predatory habits of the Bushmen were well known, as also that they were enemies of every one else, but it was supposed that they were merely another Hottentot clan. Some stories which Eva told greatly interested the Commander.

After the return of the beach rangers to Table Valley, she had gone back to live in Mr Van Riebeek’s house, and was now at the age of fifteen or sixteen years able to speak Dutch fluently.

The ordinary interpreter, Doman with the honest face, was so attached to the Europeans that he had gone to Batavia with Commissioner Van Goens, and Eva was now employed in his stead. She told the Commander that the Namaquas were a people living in the interior, who had white skins and long hair, that they wore clothing and made their black slaves cultivate the ground, and that they built stone houses and had religious services just the same as the Netherlanders. There were others, she said, who had gold and precious stones in abundance, and a Hottentot who brought some cattle for sale corroborated her statement and asserted that he was familiar with everything of the kind that was exhibited to him except a diamond. He stated that one of his wives had been brought up in the house of a great lord named Chobona, and that she was in possession of abundance of gold ornaments and jewels. Mr Van Riebeek invited him pressingly to return at once and bring her to the fort, but he replied that being accustomed to sit at home and be waited upon by numerous servants, she would be unable to travel so far. An offer to send a wagon for her was rejected on the ground that the sight of Europeans would frighten her to death.

All that could be obtained from this ingenious storyteller was a promise to bring his wife to the fort on some future occasion. After this the Commander was more than ever anxious to have the interior of the country explored, to open up a road to the capital city of Monomotapa and the river Spirite Sancto, where gold was certainly to be found, to make the acquaintance of Chobona and the Namaquas, and to induce the people of Benguela to bring the products of their country to the fort Good Hope for sale. The Commissioner Van Goons saw very little difficulty in the way of accomplishing these designs, and instructed Mr Van Riebeek to use all reasonable exertion to carry them out. The immediate object of the next party which left the fort to penetrate the interior was, however, to procure cattle rather than find Ophir or Monomotapa.

A large fleet was expected, and the Commander was anxious to have a good herd of oxen in readiness to refresh the crews. The party, which left on the 19th of October, consisted of seven servants of the Company, eight freemen, and four Hottentots. They took pack oxen to carry provisions and the usual articles of merchandise. Abraham Gabbema, Fiscal and Secretary of the Council, was the leader. They shaped their course at first towards a mountain which was visible from the Cape, and which, on account of its having a buttress surmounted by a dome resembling a flat nightcap such as was then in common use, had already received the name of Klapmuts. Passing round this mountain and over the low watershed beyond, they proceeded onward until they came to a stream running in a northerly direction along the base of a seemingly impassable chain of mountains, for this reason they gave it the name of the Great Berg River. its waters they found barbels, and by some means they managed to catch as many as they needed to refresh themselves. They were now in one of the fairest of all South African To the west lay a long isolated mountain, its face covered with verdure and here and there furrowed by little streamlets which ran down to the river below. Its top was crowned with domes of bare grey granite, and as the rising sun poured a flood of light upon them, they sparkled like gigantic gems, so that the travellers named them the Paarl and the Diamant. In the evening when the valley lay in deepening shadow, the range on the east was lit up with tints more charming than pen or pencil can describe, for nowhere is the glow of light upon rock more varied or more beautiful. Between the mountains the surface of the ground was dotted over with trees,” and in the month of October it was carpetted with grass and flowers.

Wild animals shared with man the possession of this lovely domain. In the river great numbers of hippopotami were seen ; on the mountain sides herds of zebras were browsing ; and trampling down the grass, which in places was so tall that Gabbema described it as fit to make hay of, were many rhinoceroses.

There is great confusion of names in the early records whenever native clans are spoken of. Sometimes it is stated that Gogosoa’s people called themselves the Goringhaiqua or Goriughaina, at other times the same clan is called the Goringhaikona. Harry’s people were sometimes termed the Watermans, sometimes the Strandloopers (beach rangers). The Bushmen were at first called Visman by Mr Van Riebeek, but he soon adopted the word Sonqua, which he spelt in various ways. This is evidently a form of the Hottentot name for these people, as may be seen from the following words, which are used by a Hottentot clan at the present day :-Nominative singular, sap, a bushman; dual, sakara, two bushmen; plural, sakoa, more than two bushmen. Nominative singular, sas, a bushwoman ; dual, sasara, two bushwomen ; plural, sadi, more than two bushwomen. Common plural, sang, bushmen and bushwomen. When the tribes became better known the titles given in the text were used.

There were little kraals of Hottentots all along the Berg River, but the people were not disposed to barter away their cattle. Gabbema and his party moved about among them for more than a week, but only succeeded in obtaining ten oxen and forty-one sheep, with which they returned to the fort. And so, gradually, geographical knowledge was being gained, and Monomotapa and the veritable Ophir where Solomon got his gold were moved further backward on the charts. During the year 1657 several public works of importance were undertaken.

A platform was erected upon the highest point of Robben Island, upon which a fire was kept up at night whenever ships belonging to the Company were seen off the port. At the Company’s farm at Rondebosch the erection of a magazine for grain was commenced, in size one hundred and eight by forty feet. This building, afterwards known as the Groote Schuur, was of very substantial construction. In Table Valley the lower course of the fresh river was altered. In its ancient channel it was apt to damage the gardens in winter by overflowing its banks. A new and broader channel was therefore cut, so that it should enter the sea some distance to the south-east of the fort. The old channel was turned into a canal, and sluices were made in order that the moat might still be filled at pleasure.

In February 1658 it was resolved to send another trading party inland, as the stock of cattle was insufficient to meet the wants of the fleets shortly expected. Of late there had been an unusual demand for meat. The Arnhem, and Slot van Honingen, two large East Indiamen, had put into Table Bay in the utmost distress, and in a short time their crews had consumed forty head of horned cattle and fifty sheep. This expedition was larger and better equipped than any yet seat from the fort Good Hope. The leader was Sergeant Jan van Harwarden, and under him were fifteen Europeans and two Hottentots, with six pack oxen to carry provisions and the usual articles of barter. The Land Surveyor Pieter Potter accompanied party for the purpose of observing the features of the country, so that a correct map could be made.

To him was also entrusted the task of keeping the journal of the expedition. The Sergeant instructed to learn all that he could concerning the tribes, to ascertain if ivory, ostrich feathers, musk, civet, gold, and precious stones, were obtainable, and, if so, to look out for a suitable place the establishment of a trading station. The party passed the Paarl mountain on their right, and crossing the Berg River beyond, proceeded in a northerly direction until they reached the great wall which bounds the coast belt of South Africa. In searching along it for a passage to the interior, they discovered a stream which came foaming down through an enormous cleft in the mountain, but they could not make their way along it, as the sides of the ravine appeared to rise in almost perpendicular precipices. It was the Little Berg River, and through the winding gorge the railway to the interior passes today, but when in 1658 Europeans first looked into its deep recesses it seemed to defy an entrance.

The travellers kept. on their course along the great barrier, but no pathway opened to the regions beyond. Then dysentery attacked some of them, probably brought on by fatigue, and they were compelled to retrace their steps. Near the Little Berg River they halted and formed a temporary camp, while the Surveyor Potter with three Netherlanders and the two Hottentots attempted to cross the range. It may have been at the very spot known a hundred years later as the Roodezand Pass, and at any rate it was not far from it, that Potter and his little band toiled wearily up the heights, and were rewarded by being the first of Christian blood to look down into the secluded dell now called the Tulbagh Basin.

Standing on the summit of the range, their view extended away for an immense distance along the valley of the Breede River, but it was a desolate scene that met their gaze. Under the glowing sun the ground lay bare of verdure, and in all that wide expanse which today is dotted thickly with cornfields and groves and homesteads, there was then no sign of human It was only necessary to run the eye over it to be assured that the expedition was a failure in that direction. And so they returned to their companions and resumed the homeward march.

Source: Chronicles of the Cape Commanders by George McCall Theal – 1882

The Union-Castle Line History

May 25, 2009 The Union-Castle Line, famed for its lavender hulled liners that sailed between Southampton and South Africa, began as two separate companies – the Union Line and Castle Line.

The Union-Castle Line, famed for its lavender hulled liners that sailed between Southampton and South Africa, began as two separate companies – the Union Line and Castle Line.

Search for passenger lists right here.

In 1853, the Union Steamship Company was founded as the Union Steam Collier to carry coal from South Wales to meet the growing demand in Southampton. It was originally named the Southampton Steam Shipping Company, but later renamed Union Steam Collier Company. The first steamship, the Union, loaded coal in Cardiff in June 1854 but the outbreak of the Crimean War slowed things down. After the war the company was reconstituted as the Union Steamship Company and began chartering its ships.

In 1857 the company was re-registered as Union Line, with Southampton as head office. That same year, the British Admiralty invited tenders for the mail contract to the Cape and Natal. Union Line was awarded the contract with monthly sailings in each direction of not more than 42 days, sailing from Plymouth to Cape Town or Simon’s Town. The five year contract was signed on the 12th September under the name Union-Steam Ship Company Ltd. The first sailing was from Southampton on the 15th September by the Dane.

Union Line built its first ship for the South African run and in October 1860 the Cambrian left Southampton on its maiden voyage. She could carry 60 first class and 40 second class passengers. In September 1871, bound for the cape, she ran out of coal but, under sail, completed the voyage from Southampton in less than 42 days.

By 1863 Donald Currie had built up a fleet of four sailing ships which passed the Cape on the Liverpool-Calcutta run. This company was the Castle Packet Company and was successful until the Suez Canal opened in 1869. By this time, Donald had acquired shares in the Leith, Hull and Hamburg Packet Company where his brother James was manager. The LH & H Packet Co. chartered two ships, Iceland and Gothland, to the Cape & Natal Steam Navigation Co. but this company failed. Donald then used three new Castle steamships intended for the Calcutta run on the Cape run. The ships sailed twice monthly from London with a call at Dartmouth for the mail.

In 1872 the Castle Packet Company took on the Cape run after the collapse of the Cape & Natal Line which had Currie ships on charter. Sailing from London, the ships called at Dartmouth. The service was sold under the banner “The Regular London Line”, later becoming “The Colonial Mail Line” and then “The Castle Mail Packet Company Limited”.

In 1873 Union Line signed a new mail contract including a four weekly service up the east coast of Africa from Cape Town to Zanzibar.

In 1876 the Castle Mail Packet Company Ltd was formed. Later that year, the Colonial Government awarded a joint mail contract. The service to the Cape became weekly by alternating steamers.

In 1882 the Union-Line Athenian became the first ship to use the new Sir Hercules Robinson graving dock at Cape Town. This was constructed of Paarl granite and was named after the Governor of South Africa.

In 1883 the South African Shipping Conference was formed to control the Europe -South / East Africa freight rates. The Conference was dominated by the Union Line and the Castle Mail Packet Company. Fierce rivalry between the two mail companies dominated the route until the merger in 1900. A seven year joint mail contract was signed with the clause that the companies not amalgamate.

In 1887, tickets became interchangeable on the two lines, and in 1888, the mail contract was renewed for five years (with the non-amalgamation clause).

In 1887, tickets became interchangeable on the two lines, and in 1888, the mail contract was renewed for five years (with the non-amalgamation clause).

In May 1887 the Dunbar Castle sailed from London with the first consignment of railway equipment to link the Eastern Transvaal with Delagoa Bay. The railway line was opened in 1894.

In 1890 Castle Packet’s new Dunottar Castle sailed from Southampton on her maiden voyage. It reduced the voyage to 18 days, and embarkation was switched from Dartmouth to Southampton. She had accommodation for 100 first class, 90 second class, 100 third class and 150 steerage passengers.

In 1890 Union Line’s Norseman and Tyrian, together with Courland and Venice from the Castle Packet Company began shipping supplies for transporting up river to Matebeleland. These materials were used to open up the new country of Rhodesia.

In 1891 Union Line’s Scott left Southampton on her maiden voyage reaching Cape Town in 15½ days with a stop in Madeira. In March 1893 the same ship set a new Cape run record of 14 days, 18 hours – a record which stood for 43 years. It was also in 1891 that the Castle Line replaced its Dartmouth call with one at Southampton. The Union Line now operated 10 steamships and the Castle Mail Packets Co. (renamed in 1881) operated 11 on the mail run. Both companies operated connecting coastal services to Lourenco Marques, Beira and Mauritius.

In 1893, both Union and Castle Lines began a joint cargo service from South Africa to New York. The mail contract was renewed, again with the non-amalgamation clause.

In October 1899 the Anglo-Boer War broke out. Both Union Line and Castle Packet ships ferried troops and supplies to South Africa. In late 1899, a new mail contract was offered but only one company could win the award. This led to the merger proposed by Donald. It was announced in December 1899 and Castle Line took over the fleet. The Union Line livery was black with a white riband around the hull but in 1892 this was changed to a white hull with blue riband and cream-coloured funnels. The Castle ships had a lavender-grey hull with black-topped red funnels, and this was adopted as the livery for the Union-Castle Line.

On the 13th February 1900, shareholders approved the merger. On the 8th March the merged company name was registered – Union-Castle Mail Steamship Company Ltd.

At the time of the merger, the Union Steamship fleet included the:

Arab

Trojan

Spartan

Moor

Mexican

Scot

Gaul

Goth

Greek

Guelph

Norman

Briton

Gascon

Gaika

Goorkka

German

Sabine

Susuehanna

Galeka

Saxon

Galician

Celt (on order)

The Castle Line Mail Packet Company ships included the:

Garth Castle

Hawarden Castle

Norham Castle

Roslin Castle

Pembroke Castle

Dunottar Castle

Doune Castle

Lismore Castle

Tantallon Castle

Harlech Castle

Arundel Castle

Dunvegan Castle

Tintagel Castle

Avondale Castle

Dunolly Castle

Raglan Castle

Carisbrooke Castle

Braemar Castle

Kinfauns Castle

Kildonoan Castle

Sailings from London were stopped, and the completed Celt launched as the Walmer Castle.

Sailings from London were stopped, and the completed Celt launched as the Walmer Castle.

On the 10th March 1900, Union Line’s Moor left Southampton for the last time in Union colours. On the 17th March Donald Currie hosted a reception aboard the Dunottar Castle to celebrate the hoisting of the Union-Castle flag for the first time. The Anglo-Boer War resulted in heavy military traffic for Union-Castle Line. Lord ROBERTS and his Chief of Staff, General KITCHENER, travelled to the Cape by Union-Castle.

In 1901 the Tantallon Castle was lost off Robben Island. In 1902, after the war had ended, 15 ships were laid up at Netley in Southampton Water. Nine ships undertook the weekly mail service – Saxon, Briton, Norman, Walmer Castle, Carisbrooke Castle, Dunvegan Castle, Kildonan Castle and Kinfauns Castle.

In 1910, Lord GLADSTONE, the first Governor-General of South Africa, sailed to the Cape aboard the Walmer Castle. The 1900 mail contract was extended until 1912, as the colonies united and the South African Parliament was formed under the Union of South Africa. The Prince of Wales was to sail to Cape Town, to open the new Parliament, aboard the Balmoral Castle – taken over by the Admiralty for the purpose as H.M.S. Balmoral Castle. Shortly before the ship sailed King Edward VII died and the Prince of Wales ascended the throne as H.M. King George V. He was not able to go to Cape Town and his brother, the Duke of Connaught, was sent instead.

In 1911 the Royal Mail Line bought the Union-Castle Company, taking control in April 1912. A new ten year mail contract was signed. The first new ships now bore Welsh names – the Llandovery Castle and the Llanstephan Castle.

In 1914, the Carisbrooke Castle, Norman and Dunvegan Castle were commissioned by the Admiralty – the first as a hospital ship, the latter two as troopships. By the 4th September, 19 of Union-Castle’s 41 ships were on war duty.

By 1915, Union-Castle had 13 ships in service as hospital ships. Some of the ships were lost during WWI:

28 October 1916 – Galeka was hit by a mine.

19 March 1917 – Alnwick Castle was torpedoed and sunk.

26 May 1917 – Dover Castle was sunk by a U-boat.

21 November 1917 – Aros Castle was torpedoed and sunk.

14 February 1918 – Carlisle Castle was torpedoed and sunk

26 February 1918 – Galacian was sunk by a U-boat, whilst renamed the Glenart Castle

12 September 1918 – Galway Castle was sunk by a U-boat, whilst renamed the Rhodesia

27 June 1918 – Llandovery Castle was sunk by a U-boat whilst serving as a hospital ship. 234 lives were lost, making it the fleet’s worst disaster. The Union-Castle War Memorial to those lost is at Cayzer House, Thomas More Street, London.

By October 1919, the Africa service had restarted, and Natal Direct Line had been bought. The weekly mail service resumed after WWI. The intermediate service restarted with the Gloucester Castle, Guildford Castle, Llanstephen Castle and the Norman.

In 1921 the Arundel Castle entered service. It was Union-Castle’s first four funnelled ship and the fleet’s largest ship to date. The Windsor Castle followed in 1922 and the “Round Africa” service was inaugurated.

In 1925 the Norman was withdrawn from service and the Llandovery Castle brought into service, followed by the Llandaff Castle and the Carnarvon Castle in 1926.

In 1927 the Royal Mail Line added the White Star Line. The British Treasury became involved to try and separate Union-Castle Line’s parent company from Royal Mail. By 1932 the Royal Mail group of companies (which included Union-Castle) had run into financial difficulties. Union-Castle came out of this as an independent company. In 1934 Royal Mail was put in liquidation. With heavy government involvement, Union-Castle started rebuilding.

In 1936 the Athlone Castle and the Stirling Castle entered the service. The Stirling Castle beat the record to the Cape set in 1893 by the Scot. A new ten year 14-day mail contract was signed. At this stage only the Stirling Castle and the Athlone Castle could maintain the timetable. The Arundel Castle and Windsor Castle were rebuilt, and the Carnarvon Castle, Winchester Castle and Warwick Castle were re-engined. On the 29th April 1938 the Cape Town Castle entered service. By 1939, the rebuilding programme was complete, but WWII was looming. The Edinburgh Castle became a troopship and the Dunottar Castle served as an armed merchant cruiser. After war was declared, the Carnavon Castle, Dunvegan Castle and Pretoria Castle became armed merchant cruisers.

The following Union-Castle ships were lost during WWII:

4th January 1940 – Rothesay Castle

9th January 1940 – Dunbar Castle hit by a mine and sunk.

28th August 1940 – Dunvegan Castle was sunk by a U-boat.

21st September 1941 – Walmer Castle was bombed and sunk.

12th December 1941 – Dromore Castle was hit by a mined and sunk.

14th February 1942 – Rowallan Castle was bombed by enemy aircraft.

16th July 1942 – Gloucester Castle was sunk by the German cruiser Michel.

4th August 1942 – Richmond Castle was sunk by a U-boat.

14th November 1942 – Warwick Castle was sunk by a U-boat.

30th November 1942 – Llandaff Castle was sunk by a U-boat.

22nd February 1943 – Roxburgh Castle was sunk by a U-boat.

23rd March 1943 – Windsor Castle was sunk by enemy aircraft.

2nd April 1943 – Dundrum Castle exploded and sank in the Red Sea.

During the war Union-Castle ships carried 1.3 million troops, 306 Union-Castle employees were killed, wounded or listed as missing, 62 became prisoners-of-war. The Master of the Rochester Castle, Captain Richard WREN, received the DSO. The Winchester Castle, along with the battleship H.M.S. Ramillies, lead Operation Ironclad at Diego Suarez, and was awarded Battle Honours and her Master, Captain NEWDIGATE the DSC.

By the end of WWII, the Union-Castle passenger fleet consisted of the Cape Town Castle, Athlone Castle, Stirling Castle, Winchester Castle, Carnarvon Castle and the Arundel Castle.

In 1946, South Africa sponsored a scheme for engineers and their families to emigrate from Britain to fill positions in South Africa. These passengers travelled on the Carnarvon Castle, Winchester Castle and the Arundel Castle. The Durban Castle joined the “Round Africa” route.

On the 9th January 1947, the Cape Town Castle departed from Southampton – the first passenger ship carrying post-war mail. Along with the Stirling Castle, the mail service was restored. In May the Llandovery Castle restarted the “Round Africa” passenger service.

In 1948 the Pretoria Castle (later renamed the S.A. Oranje) and the Edinburgh Castle, departed from Southampton on the 22nd July and the 9th December respectively on their maiden voyages in the mail service.

In February 1949 the Dunottar Castle returned to the “Round Africa” service. A rebuilding programme started and 13 new ships were brought in – the Pretoria Castle and the Edinburgh Castle (mail service); the Kenya Castle, Braemar Castle and the Rhodesia Castle (intermediate liners); the Bloemfontein Castle (Round Africa service); the Riebeeck Castle and Rustenburg Castle (refrigerated cargo); Tantallon Castle, Tintagel Castle, Drakensberg Castle, Good Hope Castle and the Kenilworth Castle (general cargo). The Good Hope Castle and the Drakensberg Castle were registered in South Africa

In 1950 the Bloemfontein Castle departed from London on her maiden voyage anti-clockwise “Round Africa”. In 1953 the Pretoria Castle was chosen to be the Union-Castle ship present at the Coronation Review of the Fleet by Queen Elizabeth II at Spithead on the 15th June 1953.

On the 31st December 1955, the Clan Line and Union-Castle Line merged to form British & Commonwealth. The Clan Line contributed 60% of the assets (57 ships) and Union-Castle 40% (42 ships), giving the CAYZER family control of Union-Castle. The routes and livery of each company remained unchanged.

On New Year’s Day 1959 the Pendennis Castle (replacing the Arundel Castle) departed from Southampton on her maiden voyage in the mail service. The Arundel Castle completed her 211th and last voyage from the Cape, sailing for breakers in the Far East. On the 18th August 1960 the Windsor Castle departed from Southampton on her maiden voyage in the mail service, becoming the largest liner to visit Cape Town. The Winchester Castle was withdrawn from service. Also in 1960, an explosion aboard the Cape Town Castle killed the Chief Engineer and seven officers and ratings.

In 1961, the Transvaal Castle (later renamed S.A. Vaal) was launched by Lady CAYZER. In 1962 the “Round Africa” service was closed. The Transvaal Castle departed from Southampton on her maiden voyage on the 18th January 1962. The Carnarvon Castle and Warwick Castle were withdrawn from service, departing Durban for the last time together. The Durban Castle was also withdrawn.

The Southampton Castle was launched on the 20th October 1964 by Princess Alexandra.

The Windsor Castle sailed on the 16th July 1965, accelerating the mail service to provide a Southampton – Cape Town passage in 11 days. The old 4 p.m. Thursday departure was replaced by the 1 p.m. Friday departure, which remained in place for 12 years. The Athlone Castle and the Stirling Castle were withdrawn from service.

The final cycle of weekly sailings saw the mail ships departing from Southampton in the following order: Windsor Castle, Southampton Castle, Edinburgh Castle, S.A.Vaal, Pendennis Castle, Good Hope Castle, S.A. Oranje.

In 1965 Union-Castle took over the charter of the cruise liner Reina del Mar, using her out of Southampton in the summer months mainly to the Mediterranean. In the winter she cruised from South African ports – often to Rio de Janeiro and other South American ports. The Good Hope Castle sailed on her maiden voyage in the mail service on the 14th January 1966.

The UK seamen’s strike in 1966, lasting 46 days, saw 13 British & Commonwealth Group ships laid up in Southampton Docks at the same time. The mail service became a joint operation with the South African Marine Corporation – Safmarine. The Pretoria Castle and the Transvaal Castle were transferred to Safmarine and the South African flag, becoming the S.A. Oranje and the S.A. Vaal, painted in Safmarine colours.

As the De Havilland Comet jet took to the air, mail was changed from sea mail to air mail. The Boeing 747 Jumbo Jet enabled the mass transportation of people by air. In October 1973 British & Commonwealth Shipping Company and Safmarine combined their operations under the name International Liner Services Ltd. On the 29th June 1973 a fire broke out aboard the Good Hope Castle whilst en route from Ascension Island to St. Helena. Passengers were rescued by a passing tanker. The ship was abandoned but did not sink. She re-entered the mail service from Southampton on the 31st May 1974. A world-wide oil crisis resulted in a 10% surcharge on mail ship fares. The Southampton – Cape Town mail service was temporarily slowed from 11 days to 12 days, to conserve bunker oil.

As the De Havilland Comet jet took to the air, mail was changed from sea mail to air mail. The Boeing 747 Jumbo Jet enabled the mass transportation of people by air. In October 1973 British & Commonwealth Shipping Company and Safmarine combined their operations under the name International Liner Services Ltd. On the 29th June 1973 a fire broke out aboard the Good Hope Castle whilst en route from Ascension Island to St. Helena. Passengers were rescued by a passing tanker. The ship was abandoned but did not sink. She re-entered the mail service from Southampton on the 31st May 1974. A world-wide oil crisis resulted in a 10% surcharge on mail ship fares. The Southampton – Cape Town mail service was temporarily slowed from 11 days to 12 days, to conserve bunker oil.

The S.A. Oranje departed from Southampton on the 19th September 1975 for the breakers. It was the start of the phasing out of weekly mail service.

The Edinburgh Castle’s last departure from Southampton (without passengers) was on the 23rd April 1976 for Durban, after which she went to the breakers. The Pendennis Castle was withdrawn after arriving at Southampton on the 14th June.

In 1977 a decision was made to containerise Europe – South Africa services. The company’s flagship, Windsor Castle, left Southampton on her last voyage on the 12th August, arriving back on the 19th September. She was sold for use as a floating hotel in the Middle East. The S.A. Vaal made her final arrival at Southampton on the 10th October. She was rebuilt as the Festivale with Carnival Cruise Lines on the 29th October and eventually scrapped in 2003 in Alang, India. The Good Hope Castle made her last arrival in the mail service at Southampton on the 26th September. On the 30th September, mainly in order to keep the islands of Ascension and St. Helena supplied, she made an additional voyage to the Cape via Zeebrugge, outside the mail service. She was finally withdrawn on return to Southampton on the 8th December. She was sold to Italy ‘s Costa Line as Paola C but was soon broken up. On the 24th October 1977, the Southampton Castle arrived at Southampton on her last mail service. She was sold to Costa Line but soon afterwards went to the breakers.

To keep the Union-Castle name alive, several Clan Line refrigerated ships were given Castle names and were repainted in Union-Castle colours. The last ship to fly the mail pennant for the Union-Castle Mail Steamship Company was the Kinpurnie Castle (former Clan Ross). She carried the mail on a voyage from Southampton to Durban calling at the Ascension Islands, St Helena, Cape Town, Port Elizabeth and East London. By 1981 the last of the Clan Line ships were sold. In 1982, International Liner Services Ltd withdrew from shipping after failing to compete against air travel. By 1986 British & Commonwealth had disposed of their last ship.

In 1999, the Union-Castle Line name was revived for a special “Round Africa” sailing on the old route. P & O Line’s Victoria sailed on the 11th December 1999 from Southampton on a millennium cruise with her funnel painted in Union-Castle colours. New Year’s celebrations were held in Cape Town. The Victoria returned to Southampton in February 2000.

In June 2001 the Amerikanis (former Kenya Castle) was scrapped in India, In July 2003 the Big Boat (former Transvaal Castle) was scrapped in India. In August 2004 the Victoria (former Dunottar Castle), was also scrapped in India. The Margarita L. (former Windsor Castle) was then owned by the Greek LATSIS family but in December 2004 this last ship was sold for scrap to Indian scrap merchants, ending the era of the Union-Castle Line.

Ports of Call

Royal Mail Service: from Southampton to Durban, via Madeira, Cape Town, Algoa Bay and East London. Northbound voyages called at Mossel Bay.

Around Africa service (West Coast): from London to London, via Canary Islands, Cape Town, Durban, Delagoa Bay and Suez Canal. Other ports of call were given as East African, Egyptian and Mediterranean ports. They may have included Madeira, Ascension, St. Helena, Lobito Bay, Walvis Bay, Lüderitz Bay, Mossel Bay, Algoa Bay, East London, Beira, Dar-es-Salaam, Zanzibar, Tanga, Mombasa, Aden, Port Sudan, Naples, Genoa and Marseilles.

Around Africa service (East Coast): from London to London, via Suez Canal, Delagoa Bay, Durban, Cape Town, Lobito Bay, St. Helena, Ascension, Canary Islands and Madeira. Other ports of call may have been the same as the West Coast route.

Intermediate service: from London to Beira or Mombasa, via Canary Islands and Cape Town. Occasionally called at St. Helena and Ascension on northbound voyages. Other ports of call may have included Algoa Bay (Port Elizabeth), East London, and Atlantic ports as per the “Around Africa” West Coast service.

Image Captions

“Round Africa” route, from the 1954 Union-Castle brochure

Dunottar Castle

The Union Castle Line Poster

Kinfauns Castle

References

A Trip to South Africa, by James Salter-Whiter, 1892

Ships and South Africa: a maritime chronicle of the Cape, with particular reference to mail and passenger liners, from the early days of steam down to the present ; by Marischal Murray, Oxford University Press 1933

Union-Castle Chronicle: 1853 – 1953, by Marischal Murray; Longmans, Green and Company 1953

Mail ships of the Union Castle Line, by C.J. Harris and Brian D. Ingpen, Fernwood Press, 1994

Union-Castle Line – A Fleet History, by Peter Newall, Carmania Press 1999

Golden Run – A Nostalgic Memoir of the Halcyon Days of the Great Liners to South and East Africa, by Henry Damant, 2006

Merchant Fleet Series. Vol. 18 Union-Castle, by Duncan Haws

Union-Castle Line Staff Register: http://www.unioncastlestaffregister.co.uk

Article researched and written by Anne Lehmkuhl, June 2007

Carte Blanche on Ruda's Family Tree

May 25, 2009The Wahl Family

Ruda Landman’s birthplace in the dry and dusty town of Keimoes, in the Northern Cape, is a far cry from where her family’s humble beginnings started in the lush and fertile valleys of Europe. From the Persecution of her family in France in the 1600′s, her ancestry consists of a kaleidoscope of French refugees as well as Dutch and German Immigrants.

When the French Huguenots arrived at the Cape in 1688 as a closely linked group, in contrast to the Germans, they all lived together in Drakenstein, although they never constituted a completely united bloc; a number of Dutch farms were interspersed among them. Until May 1702 they had their own French minister, Pierre Simond, and until February 1723 a French reader and schoolmaster, Paul Roux. The Huguenots clung to their language for fifteen to twenty years; in 1703 only slightly more than one fifth of the adult French colonists were sufficiently conversant with Dutch to understand a sermon in Dutch properly, and many children as yet knew little or no Dutch at all. The joint opposition of the farmers toward W. A. van der Stel shortly afterwards brought the French more and more into contact with their Dutch neighbours; as a result of social intercourse and intermarriage they soon adopted the language and customs of their new country. Forty years after the arrival of the Huguenots, the French language had almost died out and Dutch was the preferred tongue.

In South Africa we are extremely lucky to have such superb and dedicated family historians, as well as exquisite records in our Archives, which begin prior to Jan Van Riebeeck landing at the Cape. Jan’s diary of his voyage to South Africa is documented and stored in the Cape Town Archives.

This mammoth task of tracing Ruda’s family tree in record time, was compiled to find out how far back the Wahl family and its branches can be traced as well as how many sets of grandparents can be found. [click here] to view Ruda’s ancestors.

The Wahl Family